At a moment when outdated social structures are being contested and many of us are seeking ways to dismantle them, how do we think differently about cherished objects that perpetuate patriarchy? One of many exclusionary systems, patriarchy maintains cis male dominance and limits the power of women, queer folx, and transgender people in business, government, and other social spheres. What, then, can the “President’s Chair,” a beloved historical object at Harvard, tell us about patriarchy? A lot, as it turns out.

“The Right to Kiss”

A 1903 article, printed in the Cambridge Chronicle, notes that: “The President’s Chair used to stand in the Harvard library, where, according to tradition, it gave a student the right to kiss any young woman whom he was showing through the college, and who thoughtlessly sat down on it. Whether or not the privilege was often or ever taken advantage of the present generation has no means of knowing.”[1] In an earlier account, a Harvard alumnus “delivered an 1811 poetic oration to Phi Beta Kappa that tells it exactly as it was: ‘Now young gallants allure their favorite fair to take a seat in Presidential chair; Then seize the long accustomed fee, the bliss of the half ravished, half free-granted kiss.’”[2] What was it about this piece of furniture that in some minds seemingly authorized men to violate women’s rights, and how do these anecdotes help us understand the chair’s past, present, and future?

“Ancient and Weird”

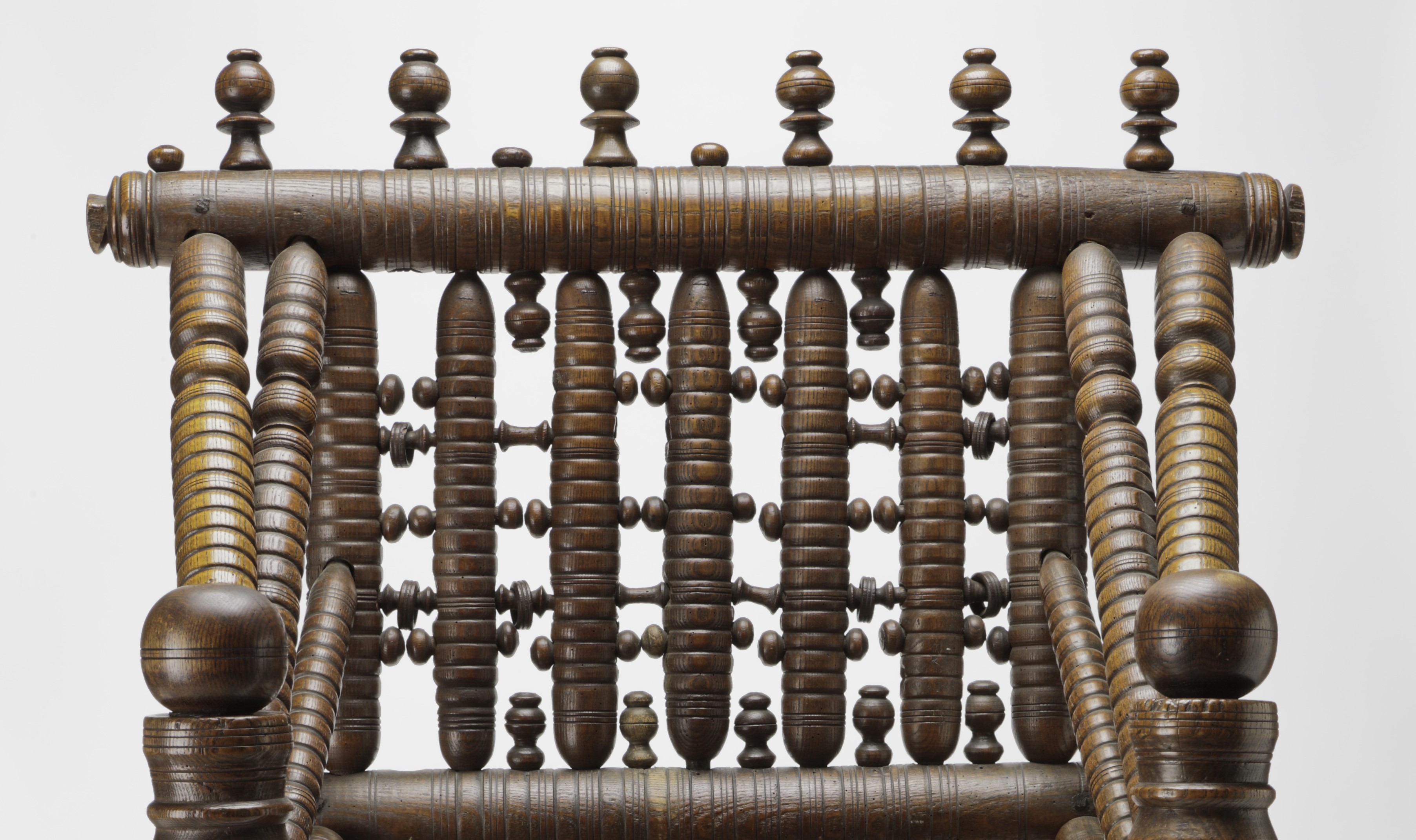

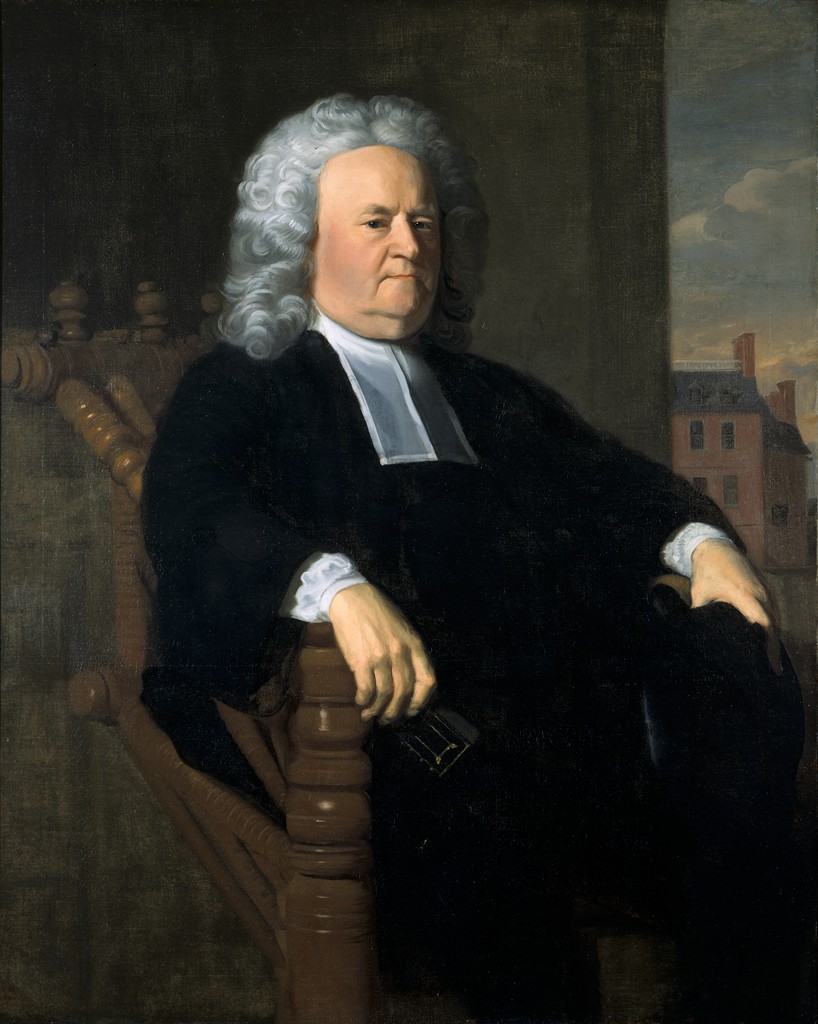

The extraordinary piece of furniture that is currently known as the President’s Chair has been at Harvard since the mid-18th century. While art critic Robert Hughes once described this object as “ancient and weird”[3], the chair had no such connotations in its previous life. Made between 1550 and 1600 in England or Wales, this three-square turned chair, to use the proper terminology of furniture historians, is made of European ash, with later additions. Edward Holyoke, Harvard president from 1737 to 1769, had oak pommels attached to the front posts after he acquired it for the university.[4] With so many turned reels, rods, posts, and other details, the complexity of the design is striking. Upon closer look, however, one can see that the chair was roughly worked, not exquisitely crafted. Grooves on the two front legs appear asymmetrically placed and slightly unevenly spaced. Small rounded elements between the spindles of the chair’s back are of varying circular and oval shapes. Vertical roundels attached to the underside of the topmost spindle differ in length and width. The roughness of the work may indicate the chair’s original purpose for regular domestic use, the skill of the maker, or both.