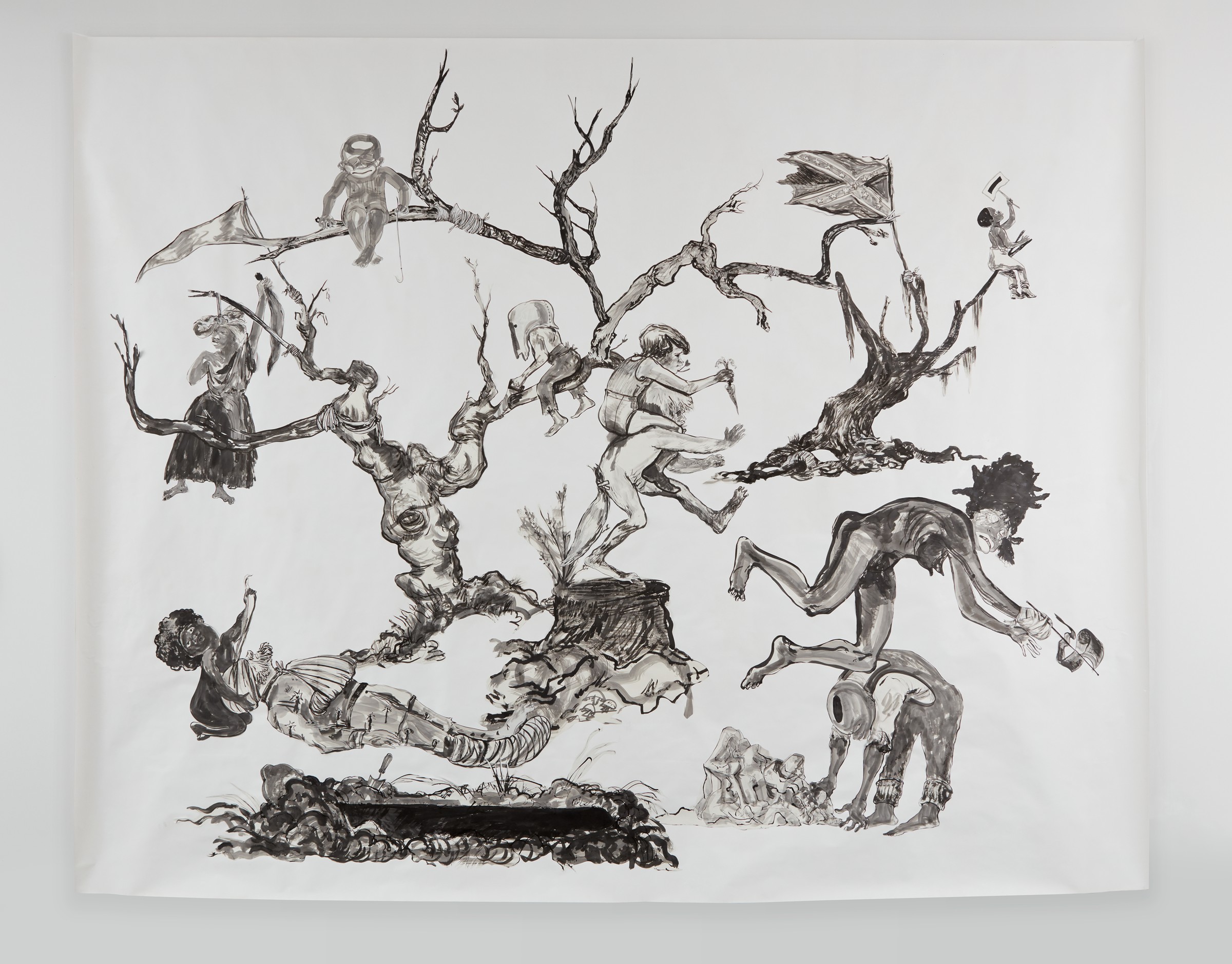

On the morning it was installed in the gallery, Kara Walker’s U.S.A. Idioms was revealed slowly, inch by inch.

The collage on paper, nearly 12 by 15 feet, had been stored around a long roller. As installers unrolled it from left to right, figures began to appear: a woman hanging from a tree branch, a girl holding bandage wraps, an inert soldier. Then, more figures and more trees, in varied stages of life and death. A white flag. A Confederate flag.

After three hours—during which a team of 11 conservators and collections management staff carefully affixed three edges of the work to the wall with tiny magnets—the entirety of U.S.A. Idioms was on view. Those in the room stepped back to take it all in.

“I’ve seen reproductions of the drawing, but this is the first time I’ve seen it in person,” said Chassidy Winestock, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History of Art and Architecture at Harvard, who has studied Walker extensively. Winestock wrote the wall label for U.S.A. Idioms as part of her internship with the museums’ Division of Modern and Contemporary Art.

“I am stunned,” she said. “At first you see it as one work; it’s so large, so encompassing—it swallows you up. But as you keep looking, you start to notice vignettes, all these separate stories.”

Gigantic and layered in its materiality, the collage is also awash in symbolism and ambiguity. It was one of a handful of works Walker produced in response to the deadly white nationalist rally and counterprotests in Charlottesville, Virginia, in the summer of 2017. When U.S.A. Idioms was shown for the first time at Walker’s show at the Sikkema Jenkins & Co. gallery in New York City that fall, a long line of people snaked around the block waiting to see it.