A tiny book in the Harvard Art Museums collections is exemplary of early Christian texts in Egypt. This so-called Gospel of the Lots of Mary offers insights into the long history of divinatory practices.

In the 21st century in the United States, where do you receive advice about how to live your life or learn about what might happen in the future? Some people grew up with the Magic 8 Ball, a black plastic sphere that could be shaken to reveal different answers, such as: “It is certain,” “Better not tell you now,” or “Don’t count on it.” Others may carefully select their fortune cookie at a Chinese restaurant, knowing that randomness plays a role in what fortune they will receive. Others might turn to tarot, selecting cards at random that reveal information about a person’s life (this method was invented in 15th-century Italy; see this 19th-century Florentine tarot card housed at the Harvard Art Museums).

Such advice-giving and horoscopic practices have been around for millennia: consider the Oracle of Apollo at Delphi, for instance. They allowed people with questions about their life to receive answers from something or someone and by seemingly random means.

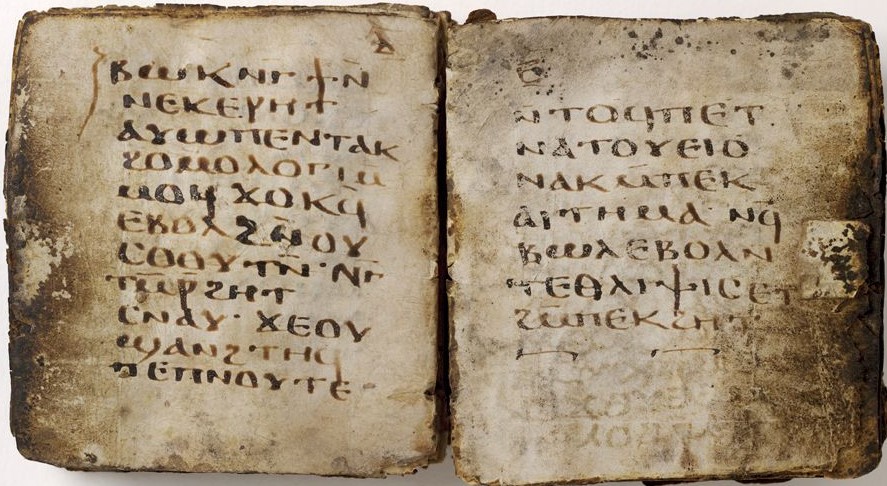

The Gospel of the Lots of Mary is a prominent material example of divinatory texts and oracles from early Byzantine Egypt (395–642 CE). At the time this miniature book (codex) was made, Christian texts were exchanged up and down the Nile, and the Christian practice of divination had expanded with the development of monasticism and pilgrimage. The book’s given title is based on the opening sentence: “The Gospel of the lots of Mary, the mother of the Lord Jesus Christ, she to whom Gabriel the archangel brought the good news.” Containing 37 oracular statements, the manuscript gives us a window into how Egyptian Christians dealt with the seeming chaos of everyday life by looking for answers about their current circumstances. These oracles either affirmed or opposed the decisions or questions that people asked. For example, in response to a question, oracle number 4 in the book tells the petitioner that “This matter that you want to do, its time has not yet come.” Oracle number 9, on the other hand, tells the petitioner to “Get up and go immediately. Do not delay.” The Gospel of the Lots of Mary functions much as if one needed to go to a religious specialist to consult a Magic 8 Ball or a fortune cookie, with both parties believing that even though the answer may look random, God intervenes in how an answer is chosen to provide exactly what the petitioner needs.

The Gospel of the Lots of Mary is written in Coptic, the final stage of the indigenous Egyptian language before the predominance of Arabic in North Africa. The codex likely dates to the sixth century CE and is written on sheepskin. Being such a small object—less than 3 inches × 3 inches—the Lots of Mary was easy to carry and store and was most likely used during one-on-one conversations rather than in Christian services. It is uncertain exactly where in Egypt the codex came from. Scholars have recently suggested that the manuscript was possibly used at the Monastery of Apa Apollo at Bawit.[1] Bawit was a village north of Asyut; a monk named Apollo founded the prominent monastery in the fourth century. In the sixth century, around the time of the codex’s creation, the monastery flourished under an abbess named Rachel.

The Harvard Art Museums acquired the codex in 1984 as a gift from Beatrice (Altmayer) Kelekian, a Radcliffe alumna and wife of Charles Dikran Kelekian, who dealt in Egyptian antiquities. The codex was published in 2014 by AnneMarie Luijendijk, a former Harvard doctoral student and current professor of religion at Princeton University.[2]