The ongoing pandemic has upended and suspended many routines and rituals that shape our perception of time, sense of order and stability, and feelings of belonging.

The selection of artworks below might prompt you to look around at home and ask: what are the objects that shape everyday practices and reflect traditions? How do they relate to the new rituals we’ve created to cope with current challenges? Are there other objects that have acquired new meaning in our present moment?

As Harvard philosopher Nelson Goodman (1906–1998) pointed out, art objects serve as symbols that help us understand the world around us. By establishing references, they enable us to construct spaces in which we can live meaningful lives. Goodman believed that art, and symbols, are indeed foundational. An ancient Mesopotamian copper statuette, which he donated to the Harvard Art Museums from his personal collection, offers tangible proof of Goodman’s insight. It had been literally inserted into the foundations of a building, likely in what is today southern Iraq, more than 4,000 years ago.

Rituals often mark special occasions, such as a significant construction project, or as an annual rite to pay respect to political leadership, as attested by the elaborate 17th-century print from Florence discussed below. A funerary ritual, which merges public and private spheres, may have been the context of display for the 12 Japanese bird-and-flower paintings featured in our Painting Edo special exhibition.

Everyday routines similarly help us navigate our lives at home, whether that is a moment of reflection with a cherished cup of tea or the more mundane practice of daily personal hygiene. Many artists represented in the Harvard Art Museums collections, past and present, would subscribe to Harvard president Larry Bacow’s encouragement to establish new rituals as we cope with unforeseen challenges. In fact, as the objects selected here demonstrate, artists have long been interested in rituals and routines; they will no doubt continue to invent and embellish them in the future, opening up new possibilities for understanding and making our lives more meaningful.

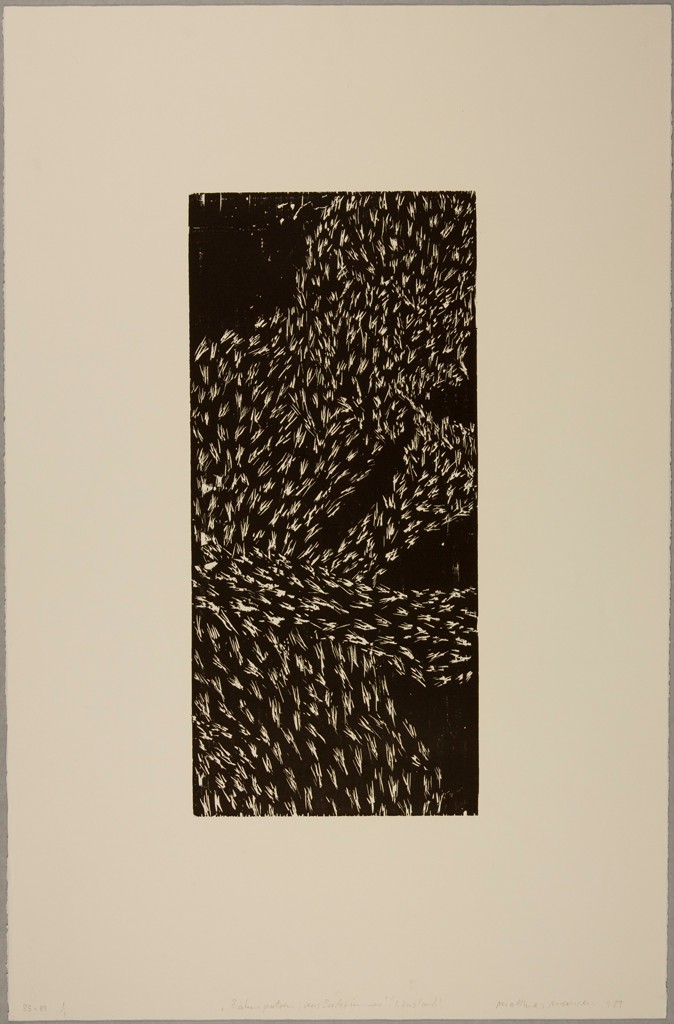

Tea Time

Imagine a chilly fall day, the scent of leaves and woodsmoke in the air. Now imagine your hands holding the bowl pictured above filled with frothy green tea, the opaque liquid emitting a curl of fragrant steam. Your pinky fingers detect the coarse stoneware foot, while your palms make contact with the smooth surface of the thick brown glaze. As you tip the bowl to take a sip, the delicate veins of a leaf are revealed.

Tea first entered China by the Tang dynasty (618–907) though Buddhist monasteries, where monks used the caffeinated beverage to sustain themselves through long sessions of meditation. The publication of the Classic of Tea (Cha Jing) by Lu Yu in the eighth century popularized the practice of tea drinking, and by the Song dynasty (960–1279), it had been taken up as a leisurely pastime. Bowls were collected and scrutinized, assessed for not only their craftsmanship but also their evocative decoration and texture.

This bowl was likely produced at the Jizhou kilns in Yonghezhen, Jiangxi province, during the Southern Song dynasty. The leaf was impressed into the body before it was submerged, rim first, into the unctuous glaze. During firing, the leaf was incinerated, leaving behind its ghostly impression, a faint reminder of the summer gone by.

Sarah Laursen, Alan J. Dworsky Associate Curator of Chinese Art, Division of Asian and Mediterranean Art