What constitutes home? Here, curatorial colleagues across divisions share examples of works of art that address domesticity. This is the first in a series of articles designed to explore the Harvard Art Museums collections through a particular lens or theme.

In the works highlighted here, home is never an empty space. Whether the artists made their home in France, Ireland, Iran, Germany, ancient Greece, or Late Antique Egypt, they focused on people and their day-to-day activities. In keeping with social mores that prevailed over millennia, women and young children are the chief protagonists, and accoutrements such as pots and pans, a broom, a loom, a grinder, and containers of household cleaners point to chores and occupations traditionally associated with women. Some of the works themselves are utilitarian objects, such as a water jar or a fragment of a textile woven with auspicious symbols. Even if well-worn, stained, or tattered, the objects—and the images that depict them—speak to the comforts of home.

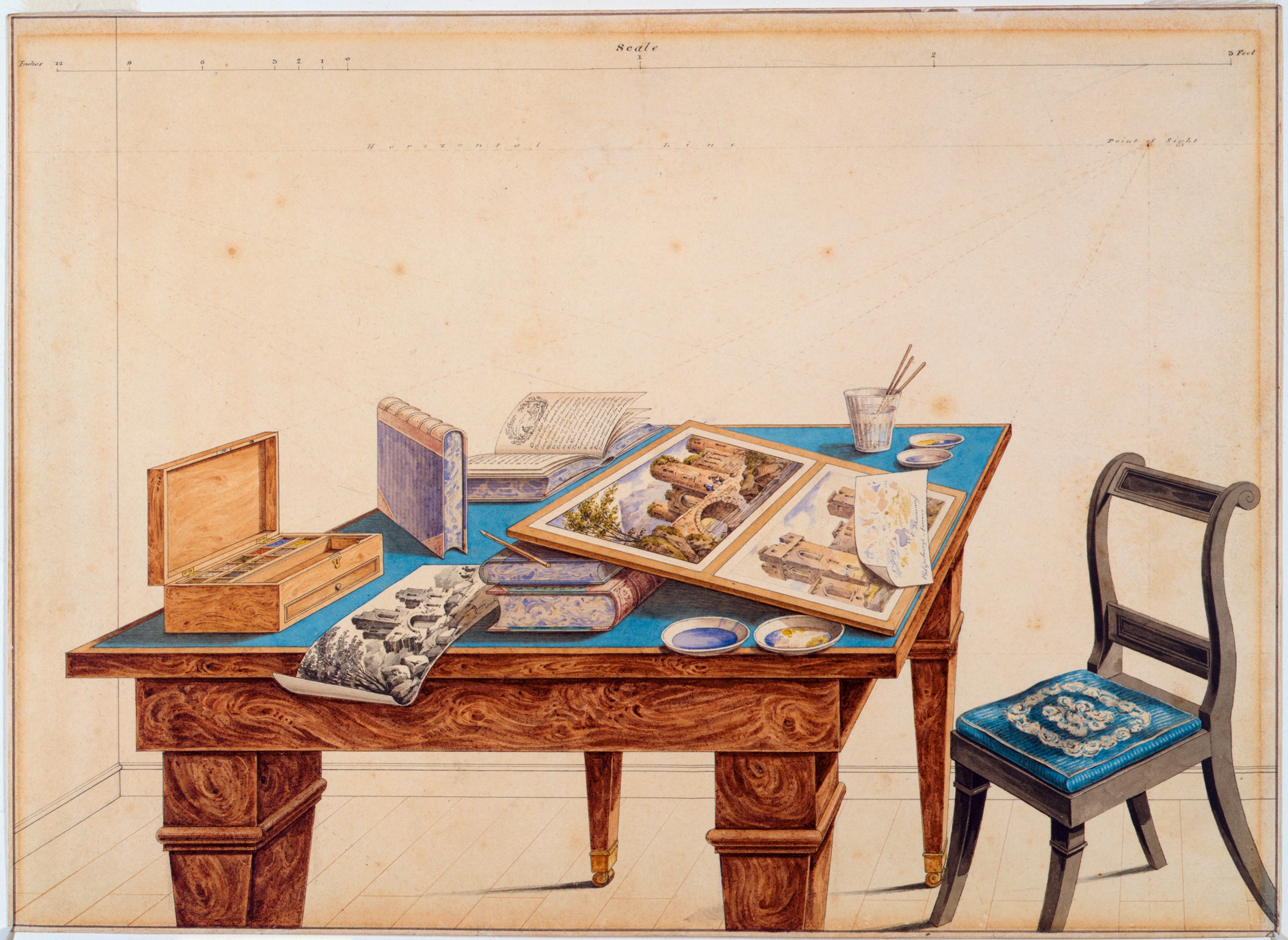

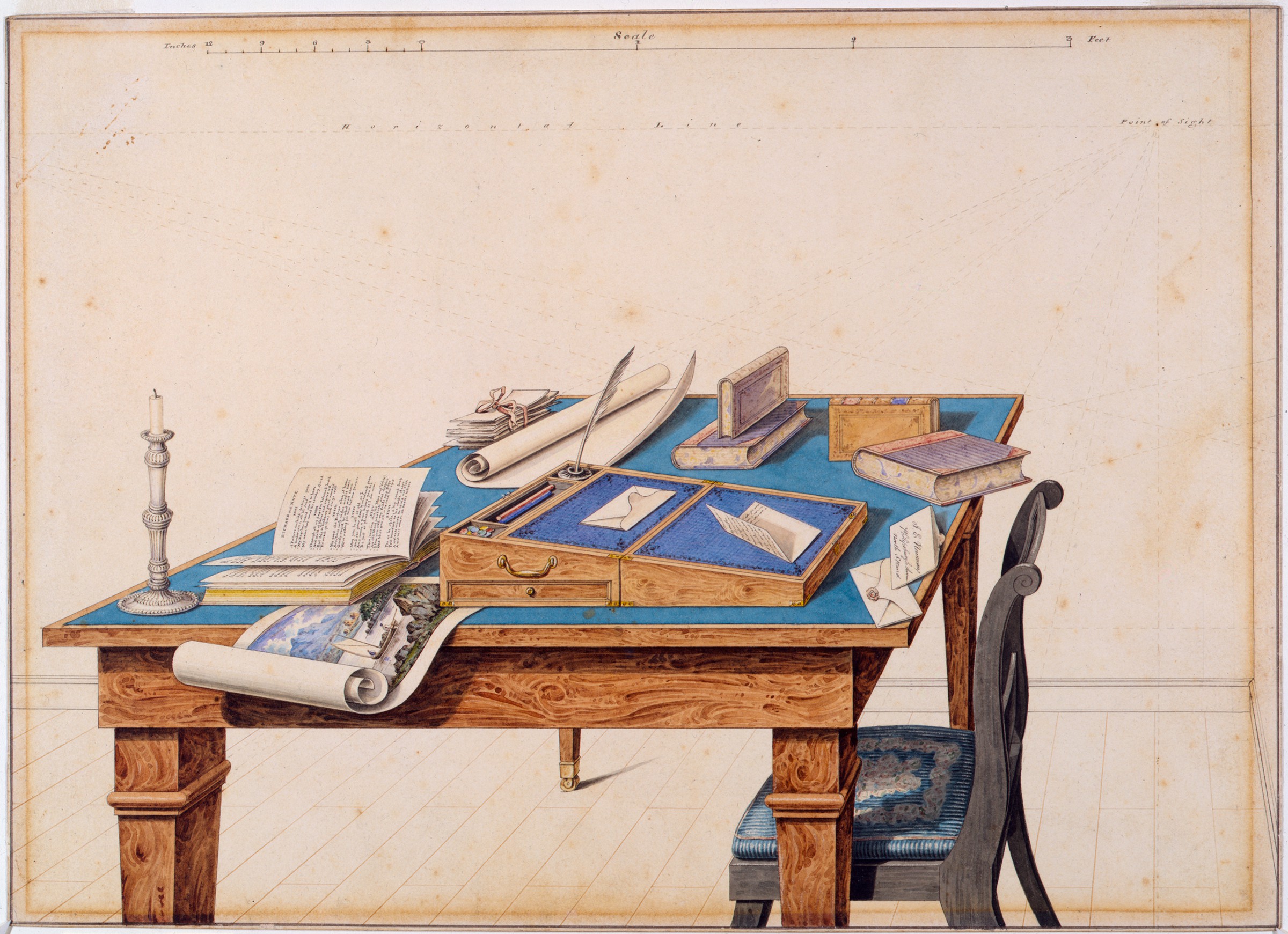

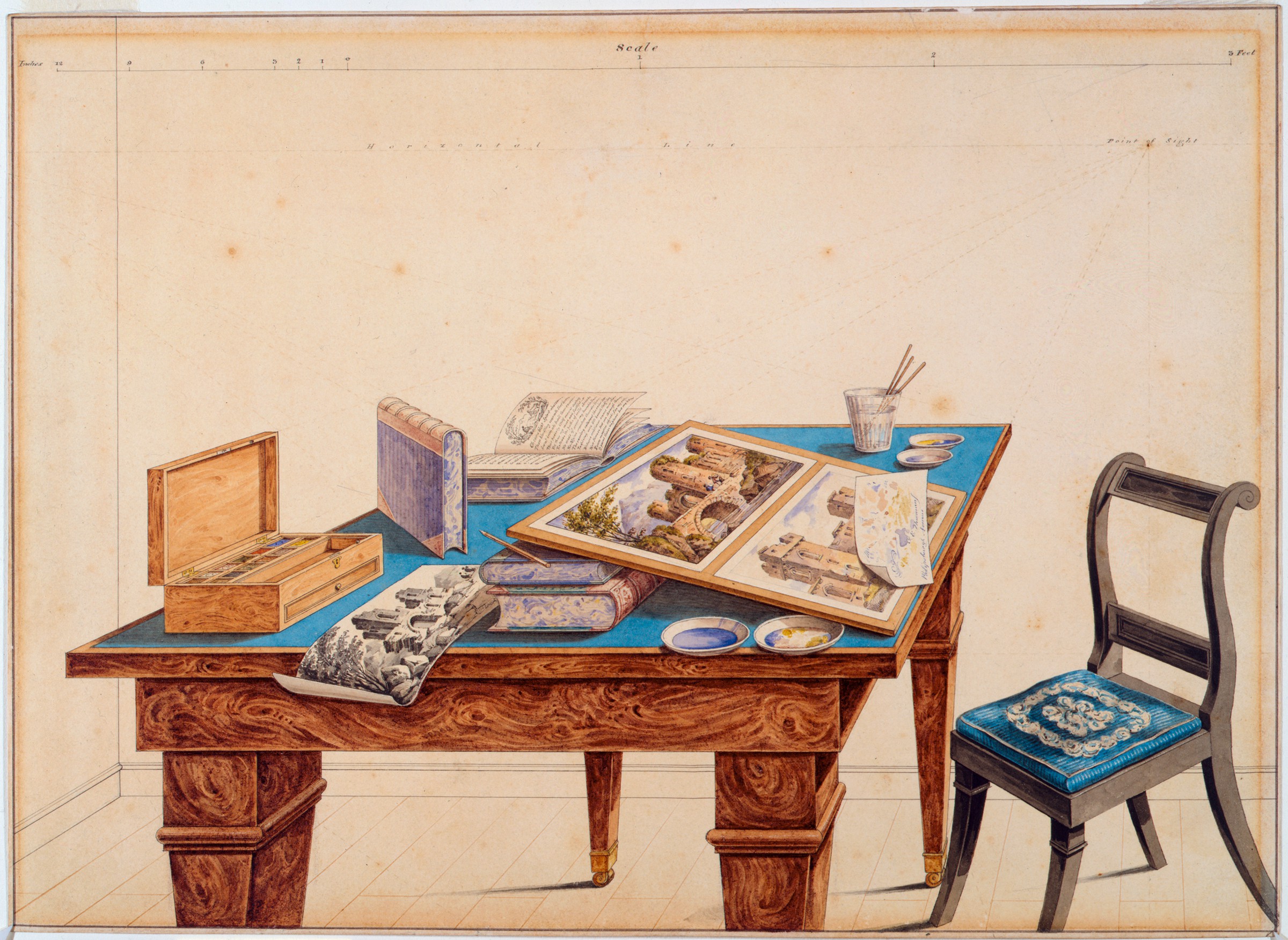

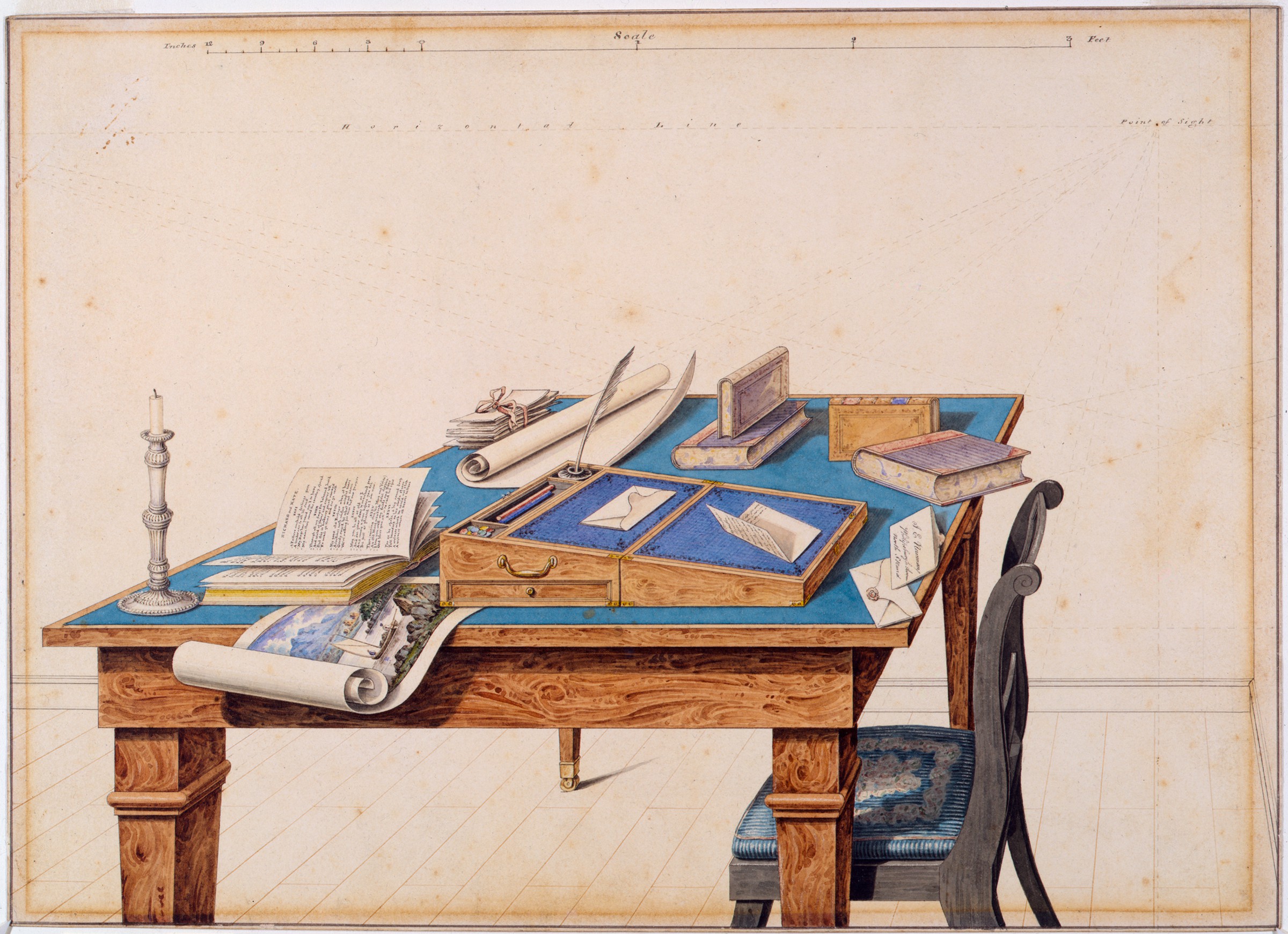

These domestic scenes are intimate without conveying isolation. In a French print, a window opens onto nature, and the viewer is positioned as if entering the room. An Iranian pen box with vignettes of a woman writing and reading refers to its own function as well as the sense of connection that can be achieved through the written word. Painted around the same time, in the mid-19th century, a pair of Irish renderings of a cluttered desk celebrate the connective power not just of the word, but also of the image: the medium of watercolor brings glimpses of the wider world into the artist’s home and at the same time allows the artist to share his view of the world (and home) with others.

Cozy Kitchen

The French print of a kitchen interior pictured above reproduces a painting by Martin Drölling (now in the Musée du Louvre, in Paris) that was exhibited to much acclaim at the Salon of 1817. The lighting and subject matter emulate 17th-century Dutch painting, which was extremely popular at the time. Art critics derided this mode of painting as pastiche, but in the wake of the political upheaval that returned the Bourbon monarchy to power, many collectors clamored to have these kinds of reassuring, familiar images in their homes. A mother and her daughter are engaged in “good” work, sewing, while another child plays peacefully on the floor with the family’s cat. The mother gazes warmly and invitingly out at the viewer, who is positioned in the kitchen as a welcome guest, perhaps even the patriarch of the family. Though the setting is rustic and humble, everyone appears content in the warmth of the family abode.

Elizabeth Rudy, Carl A. Weyerhaeuser Associate Curator of Prints, Division of European and American Art