While New England is suffering through bouts of arctic cold this winter, we encourage visitors to warm up with a number of installations focused on the theme of hell.

Hell through the Ages

On display in several galleries across all three of the museums’ curatorial divisions—Asian and Mediterranean Art, European and American Art, and Modern and Contemporary Art—these hell-themed objects are on view through winter and into spring.

“It was kind of extraordinary” when the curators realized they were planning concurrent installations around the same themes, said Miriam Stewart, curator of the collection for European and American art. However, the scheduling coincidence was simply that—a “happy accident,” said Casey Monahan, the Cunningham Curatorial Assistant for European and American art, who helped coordinate her division’s hell-themed installations.

The following groups of art are on display:

- Four prints by Robert Rauschenberg related to Dante and his Divine Comedy, in one of the modern and contemporary galleries (1100);

- Two watercolor drawings also related to Dante’s Divine Comedy, in the Pre-Raphaelite gallery (2130);

- Watercolor drawings of hell in the Divine Comedy by William Blake, in the rococo and neoclassicism gallery (2220);

- Renaissance drawings and prints depicting various interpretations of hell and purgatory, including some Dante-related material, in the Renaissance gallery (2540); and

- Four Chinese Ten Kings of Hell paintings in the hanging scroll format, in the East Asian and Buddhist art gallery (2740).

Though there are ample differences among these objects, the common theme provides an apt moment for comparison.

Treatment of the Dead

A characteristic shared among many of the works is that they portray the dead facing judgment for various sins committed during their lifetimes.

The Ten Kings of Hell paintings, for instance, draw on a medieval Buddhist text known as the Scripture on the Ten Kings. Dating to the Ming dynasty (15th–16th century), they show deceased individuals facing the judgment of a different king of the underworld every seventh day after their passing. The paintings illustrate different hells and visceral torture scenes. As the Index article “Reigning over a Hellish Bureaucracy” explains, the underworld “is driven by magistrates who mete out the punishment appropriate to each sinner who appears before them, assisted by clerks and other functionaries.” According to Wai Yee Chiong, one of the article’s co-authors and the Cunningham Curatorial Fellow in Japanese Art, the artists who created these paintings drew from multiple sources to visualize truly horrific punishments, such as being boiled in flaming cauldrons or forced to climb mountains of blades.

European Renaissance artists with a Christian worldview had somewhat similar interpretations of the activities that occurred in hell (despite obvious religious differences). In their art, sinners’ punishments include being subjected to flames, monsters, and torture.

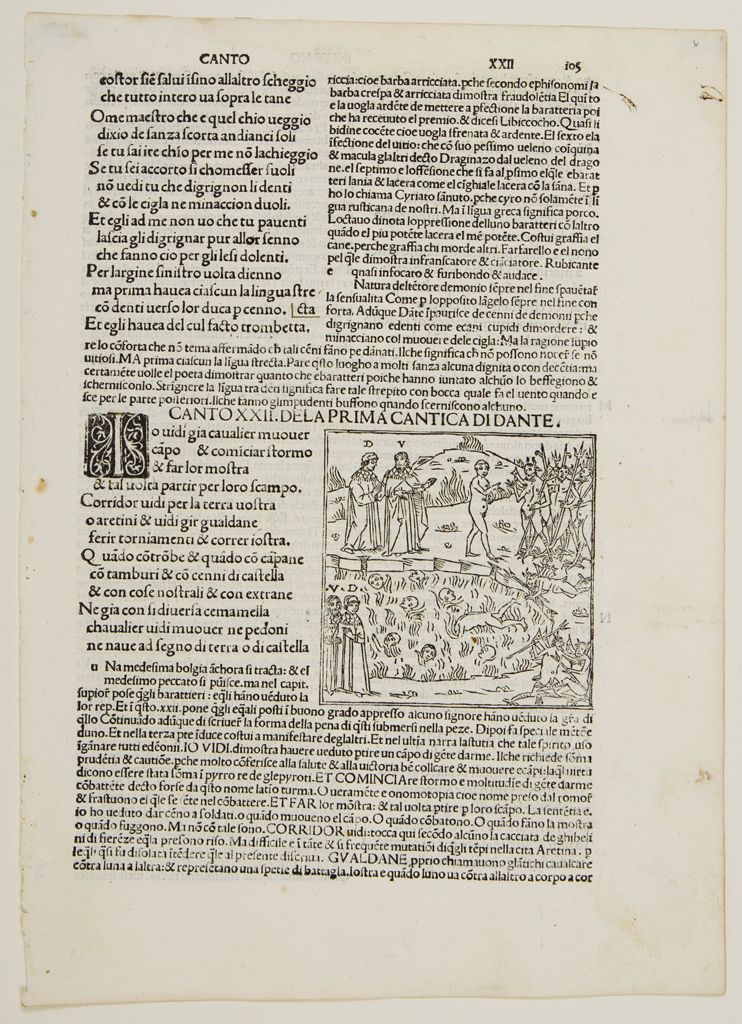

Many of the works on display in gallery 2540 are either directly or implicitly related to interpretations of Dante’s Divine Comedy (of which the Inferno is a part), the epic 14th-century poem that figured prominently in the collective consciousness of Renaissance Europeans, and that persists in popularity today. (Later in the spring, there will also be a Dante-related installation in the Lightbox Gallery; keep an eye on our calendar for further details.)

“Dante-related motifs reappear continually throughout the history of art in the West,” said Danielle Carrabino, associate research curator in European art. “He’s such a visual poet, so his work lends itself really well to artistic interpretation.”

In Dante’s poem, the deceased’s punishments related directly to transgressions committed during life. This concept is seen in some examples of Renaissance art, including in an unidentified European artist’s image of Dante’s eighth circle of hell. In this image, grafters (corrupt politicians) suffer eternity in a pool of boiling pitch “that is as sticky as the deals they made during their lifetimes,” Carrabino said. These works “were intended as warnings, reminding the viewer to lead a virtuous existence.”

Some of the prints exhibited in this same gallery served as illustrations for editions of The Divine Comedy. An etching by Jacques Callot after Bernardino Poccetti (c. 1612) portrays Dante’s inferno, which was formed by nine concentric circles, each reserved for a specific sin. As in the Ten Kings of Hell paintings, the Callot etching vividly displays acts of torture—the dead are shown enduring pitchfork prodding, beatings, and other brutality at the hands of demons.

Dante’s concentric circles are another notable feature of the arresting Callot work; they give the print a three-dimensional, almost geographic quality. A number of other pieces in the installation—including The Descent into Limbo (c. 1550), by an unidentified Netherlandish artist, and Hell (1569), by Philips Galle after Maarten van Heemskerck—also repeat the circular composition.

Creative License

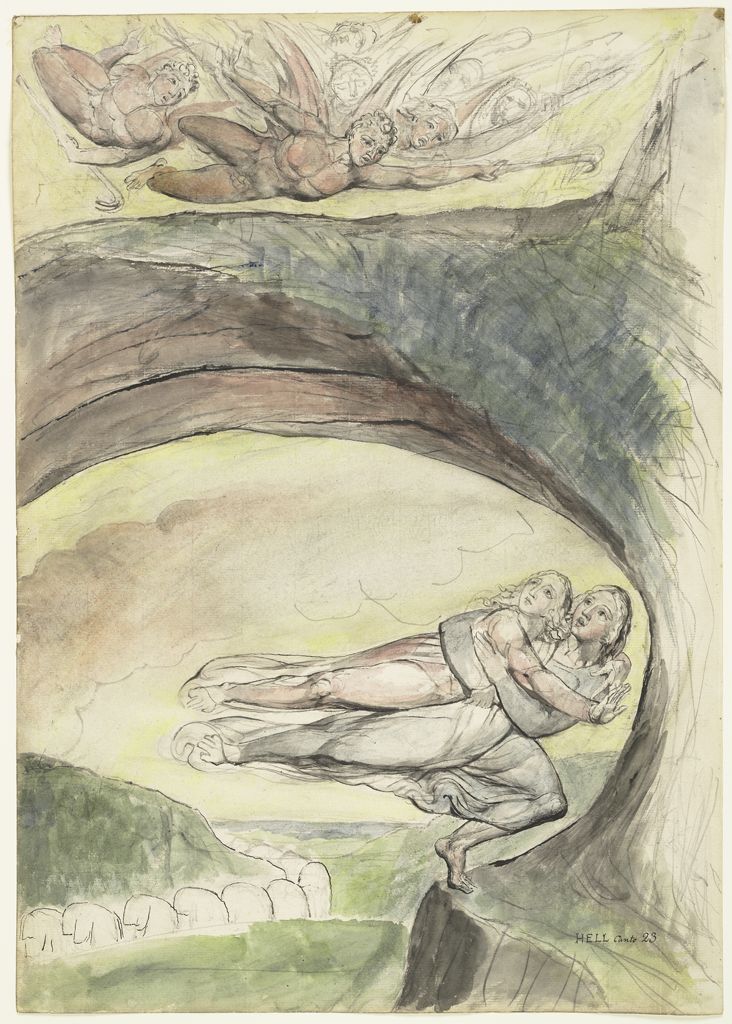

Centuries after the Renaissance, Dante’s inferno continued to inspire artists in the West. The 19th-century British artist and poet William Blake famously illustrated more than a hundred scenes from the Divine Comedy in watercolor; 23 of them were added to the Harvard Art Museums collections in the first half of the 20th century as part of the bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop.

Unlike the highly detailed and polished scenes in the Renaissance works and the Ten Kings of Hell paintings, Blake’s drawings are loosely sketched and appear to be in various states of completion. The four examples in gallery 2220 include colorful and vivid depictions of Dante's travels through inferno by the side of the poet Virgil, as described in various cantos (sections) of the Divine Comedy. The scenes include fantastical details, such as the otherworldly rock formation and sideways flight of Dante and Virgil in Dante and Virgil Escaping from the Malebranche [Devils], but they are also “more peaceful” compositions, in a sense, than many of the fury- and fear-filled scenes in other hell-themed works, said Carrabino. Even with Blake’s Ciampolo the Barrator Tormented by the Malebranche [Devils], in which Ciampolo’s skin is being removed in an excruciating manner, there is a more focused and less busy atmosphere than, for example, in this Ten Kings of Hell painting.

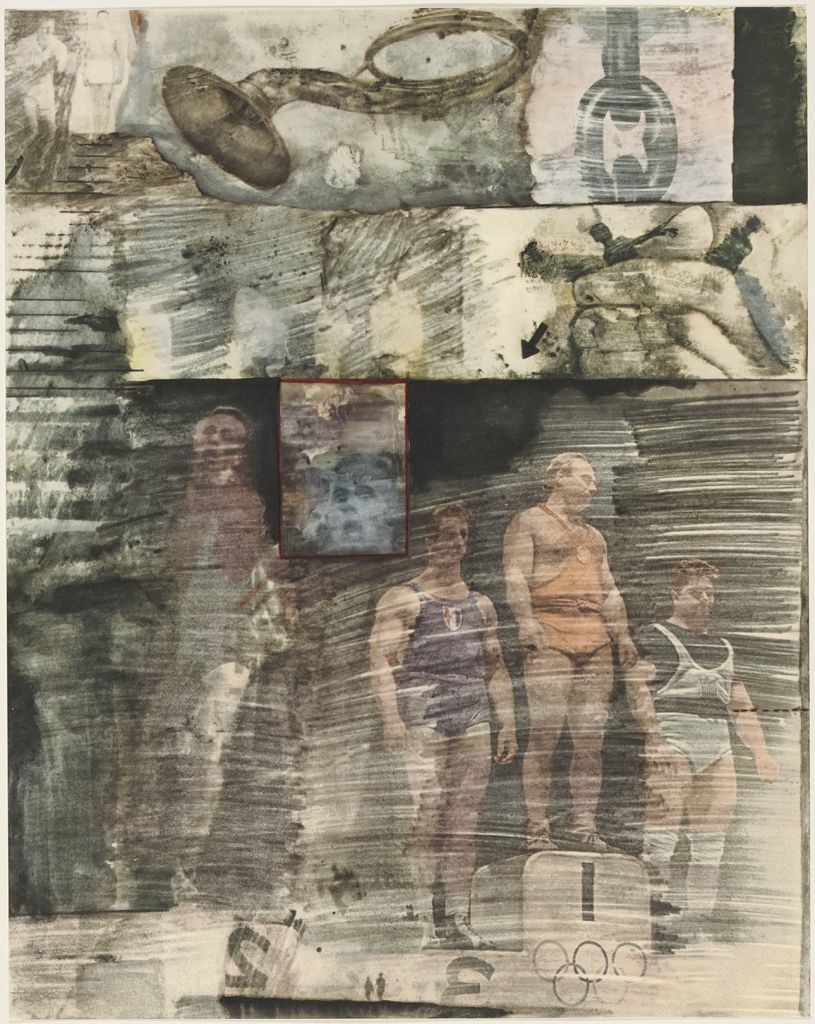

Modern American artist Robert Rauschenberg presented an entirely different perspective on the Inferno with his series XXXIV Drawings for Dante’s Inferno (1964), shown in gallery 1110. Like Blake’s series, each of Rauschenberg’s prints represents a different canto from the poem—but the works are made using a novel transfer technique. Rauschenberg applied solvent to magazine or newspaper images and then ran over them with a pencil to make compositions that were then reproduced as a print portfolio.

Though Dante’s Inferno presented classical subject matter, which helped certain audiences better connect with Rauschenberg’s abstract work, the artist took a more interpretive route in illustrating these scenes. Using the transfer technique, he incorporated contemporary issues and popular imagery, such as Olympic athletes and national guardsmen, into his prints, giving them a chaotic, collage-like appearance and a charged political tone.

Though viewers may find it more difficult to identify figures, scenes, or imagery of the Inferno in Rauschenberg’s prints, they share an important commonality with other hell-themed works on view, such as the Ten Kings of Hell paintings and the Renaissance works. In each example, it is clear that the artists enjoyed a certain amount of creative license in imagining their own versions of hell.

Between Life and Death

These works also share an interest in the expression of liminal space, particularly of that between life and death. Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix (1871) and Giotto Painting Dante’s Portrait (c. 1859) are two such examples. (Rossetti, who rearranged his first and middle names in tribute to Dante, was a translator of the poet.)

Beata Beatrix, a watercolor reproduction of Rossetti’s original (and famous) oil painting Beata Beatrix (c. 1864–70), shows the object of Dante’s affection, Beatrice (or Beatrix), from Dante’s collection of sonnets La Vita Nuova. Numerous symbols in the work allude to Beatrice’s impending death, including a dove holding a poppy.

Giotto Painting Dante’s Portrait pays homage to Dante in another way, by representing a great artist—Giotto—painting the equally esteemed poet. This could be interpreted as another “alternative” sort of afterlife for Dante: imagined immortality by way of Giotto’s paintbrush.

Overall, the many hell- and afterlife-themed works now on view have much to tell about how artists imagined and understood the unknown. Despite different histories, geographies, and cultures, artists who represented or were inspired by various aspects of hell or hell mythology grappled with some of the same limitations and embraced some of the same freedoms.

“Hell is where the imagination comes out,” Carrabino said. “It reveals anxieties, religious values, and cultural and social beliefs about how to lead a good life. It’s a moment for artists to be inspired by nature but also to use their own inventive powers to create a new world.”

Added Stewart: “It’s an endlessly fascinating subject.”