Nearly a hundred years ago, German-born artist George Grosz took a hard look at the streets of Berlin: poverty, hunger, and the ongoing war contributed to a restless, uneasy atmosphere, involving rioting, theft, and random acts of violence. Grosz depicted that sense of bedlam in his 1916 drawing Terror in the Streets.

“What he captured is the simultaneity of very violent actions and his vision of Berlin as a city in chaos,” said Ilka Voermann, the Renke B. and Pamela M. Thye Curatorial Fellow in the Busch-Reisinger Museum. “There’s a kind of spiral, or overlapping, of people and arms and heads and legs that gives us an impression of how wild street life and riots could be.”

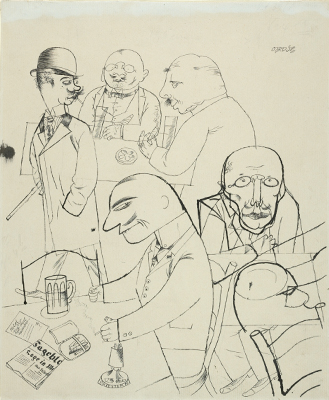

Terror in the Streets is one of two ink drawings by Grosz that have been recently installed in a gallery dedicated to art in Germany between the world wars; they are part of the first major rotation of works since the museums reopened last November. The other drawing, Café (c. 1919), presents a coffeehouse crowded with unsavory characters, many of whom appear in other Grosz drawings from the period. Voermann will discuss these works at a drop-in, 30-minute In-Focus gallery talk on April 1.

The drawings’ rotation into the galleries is an opportunity to learn more about Grosz’s broader artistic production. On view nearby, Nutcracker from 1931 is an example of the artist’s later painting style. Although the painting’s surreal assemblage of Germanic kitsch and clichés (nutcracker, castle, and pine forest) is dramatically different from the agitated drawings Terror in the Streets and Café, the artist retains his satirical edge. On the eve of his emigration from Germany, Grosz alludes here to the rise of nationalist militarism in the preceding years.

Threatened by the Nazis for being both a modern artist and a critic of the regime, Grosz immigrated to New York City in 1933 and became an American citizen in 1938. In the ensuing years, he struggled with his role as an émigré, and with establishing himself as a figurative artist. That inner conflict may be reflected in his 1948 watercolor Uprooted (The Painter of the Hole), currently on view near work by other European émigrés working in the United States. Also on display is one of his sketchbooks, featuring sketches of assorted subjects, including the New York City skyline.

“Grosz is a great example of the limits and advantages of art historical and stylistic categories,” Voermann said. “Of course, terms like Dadaism, expressionism, and New Objectivity help us understand the general development of art history. But when you look at an artist like Grosz, who was associated with all of these different styles at various moments during his life, you can appreciate how important it is to think outside the box.”