The Robert S. and Betsy G. Feinberg Collection is an extraordinary collection of more than 300 works that spans the breadth of Edo period (1615–1868) painting in Japan. The collection has been generously promised to the Harvard Art Museums. Every six months, a new selection of works from the collection is installed in the East Asian Art gallery on Level 2 of the museums (2600); this series, Focus on the Feinberg Collection, will provide a taste of the latest installation.

It may seem counterintuitive to many of us today, but creating deliberately unpolished ink paintings was an established practice among certain Japanese and Chinese painters. In China, these paintings were made by scholar-gentlemen who immersed themselves in the arts and avoided politics and commerce. Created with economical brushwork, their paintings sought to reveal the essence of a subject rather than a precise visual likeness. The works were not originally intended for sale, but instead to be exchanged between friends.

Literati painting practice has a long history in China, but it wasn’t until the 17th century that Japanese painters began to produce their own so-called amateur works, referred to as “Nanga” (literally, “Southern painting”) or bunjinga (literati painting). Japanese Nanga painters were from a wider variety of social classes than their historical Chinese counterparts. They acquired their techniques and compositional conventions from the study of imported Chinese paintings and from Chinese painters residing in the Japanese port city of Nagasaki. Woodblock-printed painting manuals provided critical access to images of Chinese literati paintings, codifying and reproducing fundamental techniques.

In following Chinese models, Japanese painters explicitly acknowledged their debt to Chinese literati painting conventions, but they also added their own fresh perspectives and approaches. The results were often bold and playful. The objects recently installed from the Feinberg Collection exemplify these lively works and include paintings by some of the best-known Japanese Nanga painters. They will remain on view until June.

Rachel Saunders, the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Associate Curator of Asian Art, said the installation of hanging scrolls, folding screens, woodblock-printed books, and folding fans showcases dynamic approaches to the traditional practice.

“Ink painting is often seen as difficult, in particular because the use of color is severely curtailed and the works themselves can often appear under-skilled at first glance,” Saunders said. “But this is deliberate—and deceptive. What the simplicity of ink-on-paper paintings really invites you to do is to look so closely that you intuit the essence of what you are being shown. In this way, these works have an incredible power to draw you in, to transport you to other places and times through the recognition of something as simple as the texture of the bark of a pine tree or the faceted surface of a rock.”

Don’t miss:

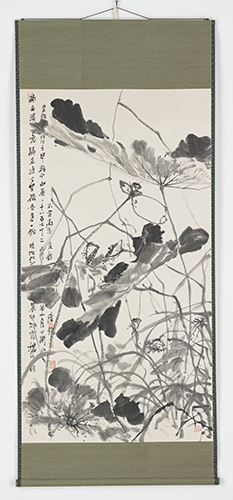

The hanging scroll Lotus in Autumn (1872) was created by Okuhara Seiko (1837–1913), a female artist who challenged the overwhelmingly male-dominated world of painting in Meiji Japan. The scroll’s composition is arresting: a broad leaf at the top of the scroll shields the last remaining lotus petals against cool autumn winds, while dry leaves and stalks entirely fill the field of view, extending well beyond the boundaries of the painting proper. A lyrical poetic inscription is wrapped around the clustered stalks on the left side of the work.

Urakami Shunkin’s (1779–1846) Precipitous Rocks and Rushing Water (1843), a pair of large, six-panel folding screens, depicts a pristine Chinese landscape, complete with stands of bamboo, waterfall, and rocky lakeshore. Smaller-scale literati landscapes, in hanging scroll or album format, invite the viewer to mentally enter and wander within the painting; the large size of this work also physically immerses the viewer in the painted landscape. This pair of screens is a striking example of how Japanese artists reinterpreted literati painting conventions.

Poetry Gathering at the Lanting Pavilion (1805), a monumental hanging scroll, is painter Ki no Baitei’s interpretation of the legendary literary gathering of scholars held by the celebrated Chinese poet and calligrapher Wang Xizhi in the spring of 353 CE. The poets drank wine from cups that floated by on a meandering stream near the Lanting, or Orchid Pavilion. Baitei’s immersive scroll challenges viewers to find the tiny details and individual figures in the intricately painted landscape, including the generous host, the many poets at work, and the hard-working attendants retrieving empty wine cups downstream.