Robert and Betsy Feinberg have worked over several decades to create an extraordinary collection of Japanese art, with a particular focus on paintings from the early modern Edo period (1603–1868). In 2009, the Feinbergs generously promised the collection to the Harvard Art Museums. Every six months, a new selection of works from the collection is installed in the East Asian Gallery on Level 2 of the museums.

Focus on Feinberg: Maruyama-Shijō Painting

Our latest installation highlights paintings in the collection by masters of the Maruyama-Shijō School, a highly innovative and phenomenally successful school of painting that originated with the painter Maruyama Ōkyo (1733–1795) and his foremost pupil, Matsumura Goshun (1752–1811), working in the Shijō or “Fourth Avenue” district of the capital city, Kyoto.

“There’s a lucidity and a freshness to these works that beckons to both the first-time viewer and the frequent flyer alike,” said Rachel Saunders, the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Associate Curator of Asian Art. “These are paintings that really move toward the viewer, that ask you to connect.”

Read on to learn more about must-see highlights, on view throughout the fall semester.

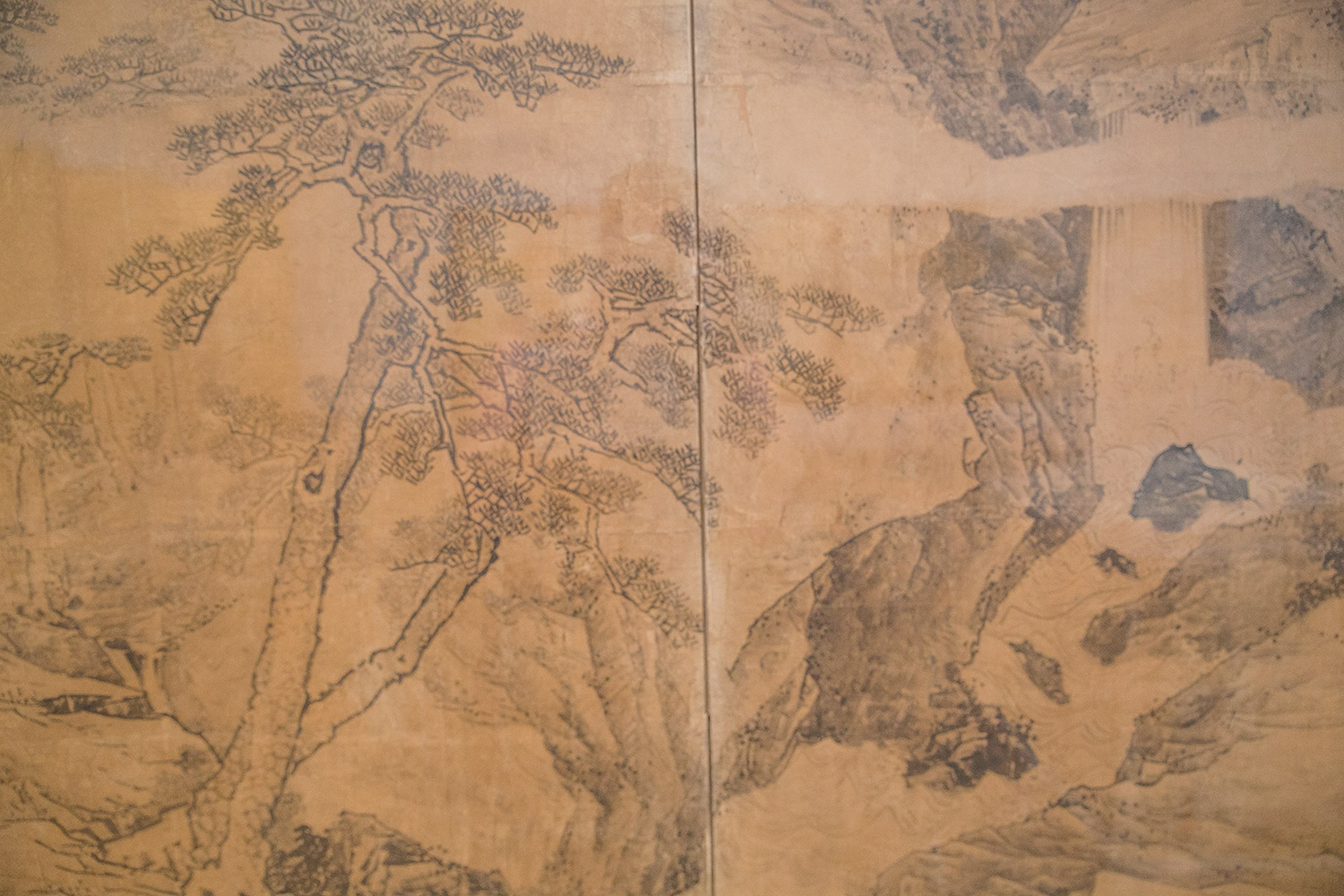

Waterfall and Pines

“Often the story told about Maruyama Ōkyo is that he was a revolutionary figure in the history of Japanese painting because he exploited painting conventions native to Western image-making, which he was familiar with by way of imported Western prints, for example,” Saunders said. “But one look at Ōkyo’s work reveals something much more complex and interesting.” “Waterfall and Pines” (1772) is a good example. It at first appears to be a conventional monochrome ink landscape depicting stock motifs, including the waterfall and the stately pines that surround it. Such ink landscapes usually required the viewer to mentally enter into the painted landscape to experience the natural phenomena rendered with familiar inky economy. But here Ōkyo also plays with the sort of illusionism more commonly associated with the compositional vocabulary of Western painting, creating a torrent of water that rushes out of the bottom of the picture plane and directly toward the viewer.

Landscape in a Rainstorm

A solitary boatman struggles to reach shelter amid a torrential downpour, battling wind and waves, in this magnificent painting in ink on silk by Maruyama Ōkyo. Once again, the artist enlivens this traditional Chinese ink painting subject with his intensely proximate vision of the storm, using massive wet brushstrokes to bring the wind and rain into being above the tiny figure of the boatman.

Landscape

Watanabe Shikō’s “Landscape” takes time-honored themes usually found in modest handscroll, hanging scroll, or album format ink paintings—subjects that include rustic fishing villages, angular pines, and geese coming in to land at dusk—and here expands them across the full length of this spectacular pair of golden folding screens. “Painting with ink on non-absorbent gold foil is an extremely tricky proposition. This work is completely virtuosic in its demonstration of the painter’s control over his materials,” said Saunders.

Eight Chinese Immortals of the Wine Cup

This painting depicts the so-called Eight Immortals of the Wine Cup; it was created by eight students of Maruyama Ōkyo and Matsumura Goshun, inheritor of the Ōkyo line. Each artist painted one of the immortals and affixed his signature and seal next to his figure. The grouping sends up the conventional Eight Daoist Immortals: the drunken sages shown here were all historical Tang dynasty scholars “immortalized” in a humorous poem about their special gifts and varying capacities for alcohol by the great Chinese poet Du Fu (712–770). This humorous collaborative painting also presented an opportunity for the artists to paint themselves into the Maruyama-Shijō lineage.