Art allows both artists and their audiences to disregard bleak realities and enter a world of their own imagination, however transient. A recent Index article discussed the political engagement of artists; the present one explores artists’ retreat into pleasant pastimes, dreamlands, exuberant ornamentation, and fantasy.

In a Culture Track survey carried out this spring, respondents said that they look to cultural institutions to help them “laugh and relax” and “offer distraction and escape during the crisis,” and that the majority of those eager to visit an art museum want to experience beauty. The artworks selected here respond to this impulse by representing escapes from immediate danger, health and political crises, the demands of daily life, and even the rules of nature.

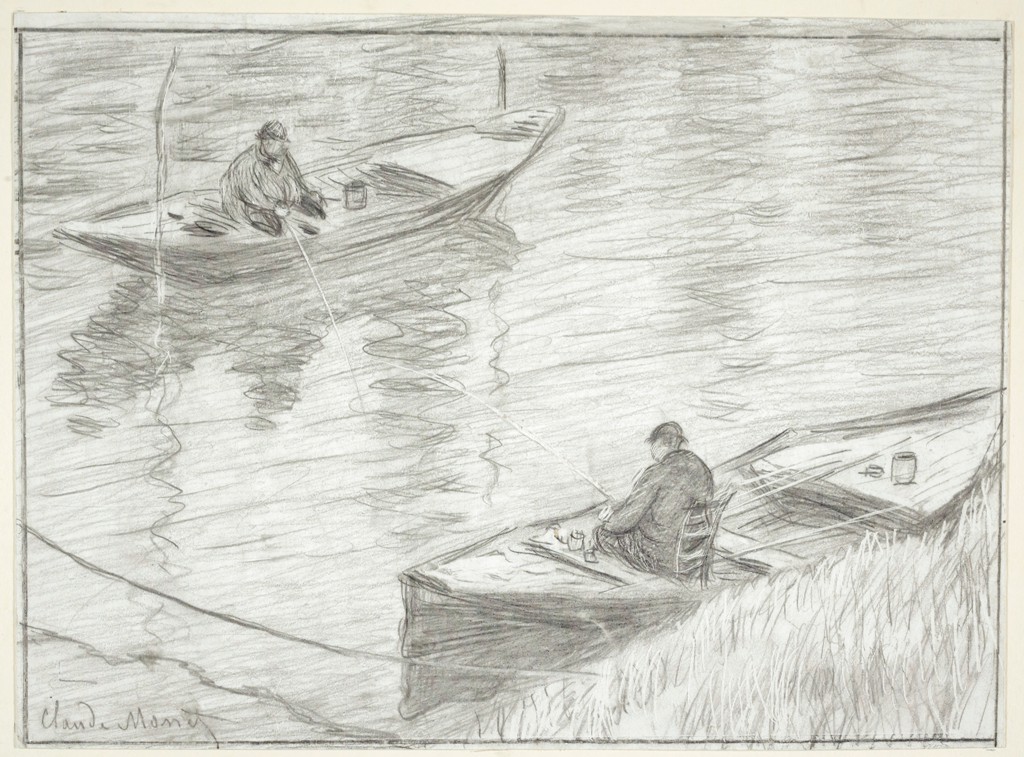

A little bronze figure invites us to forget our worries and tag along on the adventures of the great escape artist Odysseus, for what is the Odyssey but a series of narrow escapes from hairy situations? A drawing by Claude Monet hints at the close personal connection that may be found in a shared pastime amid the tranquility of nature. A painting by Japanese artist Watanabe Gentai conjures up a fleeting pastoral idyll in brilliant colors—look closely, since you may not be able to return. An elaborately decorated Athenian water jar shows that the craving for beauty in times of crisis dates back millennia. And a grotesque bird by Dutch metalsmith Arent van Bolten takes us on a (wingless) flight of fancy, revealing the artist as a creator who may ignore the rules of nature to build an alternative universe.

Going Out on a Lamb

In the aftermath of Hurricane Hugo, my father found himself with the charge of entertaining me for months. Without electricity, the still, dark evenings were hard to bear, so he filled them with legends. Half-remembered stories inspired new narrations and were my introduction to the tale enfolded in the small sculpture seen above: the elaborate escape by Odysseus and his men from the cave of the Cyclops Polyphemus. After inebriating their captor, Odysseus lied about his name and blinded the Cyclops’s one eye with the aid of his men. The Greeks then absconded under the bellies of thick-fleeced sheep, where they were hidden from Polyphemus’s probing touch. In a rare flash of tenderness that moved me as a child, Polyphemus imagined that the burden that slowed down his favorite ram was sadness for his lost eye and not the added weight of the hidden Odysseus.

Figurines can be small and simple, yet profoundly evocative. Here, Odysseus pokes his head out from under the ram, foreshadowing the boastful reveal of his identity that will curse him to a 10-year voyage. The ram smiles in turn, knowing perhaps that the trespasses against its master will not go unpunished. The two bodies here, alone and summarily rendered, contain an epic and encourage the beholder to join in on the adventure. Is it possible that the feel of this sculpture inspired a parent trying to comfort their child all these centuries ago?

Frances Gallart Marqués, Frederick Randolph Grace Curatorial Fellow in Ancient Art, Division of Asian and Mediterranean Art