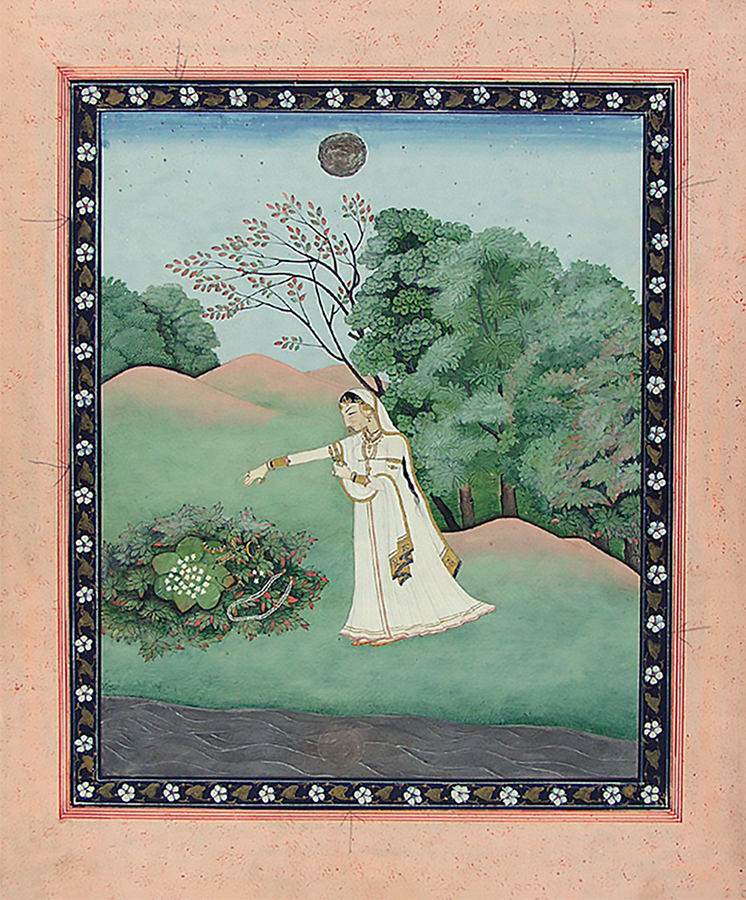

A woman has just discovered that her lover is unfaithful. With head bowed, she casts off his gifts of gold jewelry. She is the Vipralabdha nayika.

Nayikas: Love’s Beauty and Perils

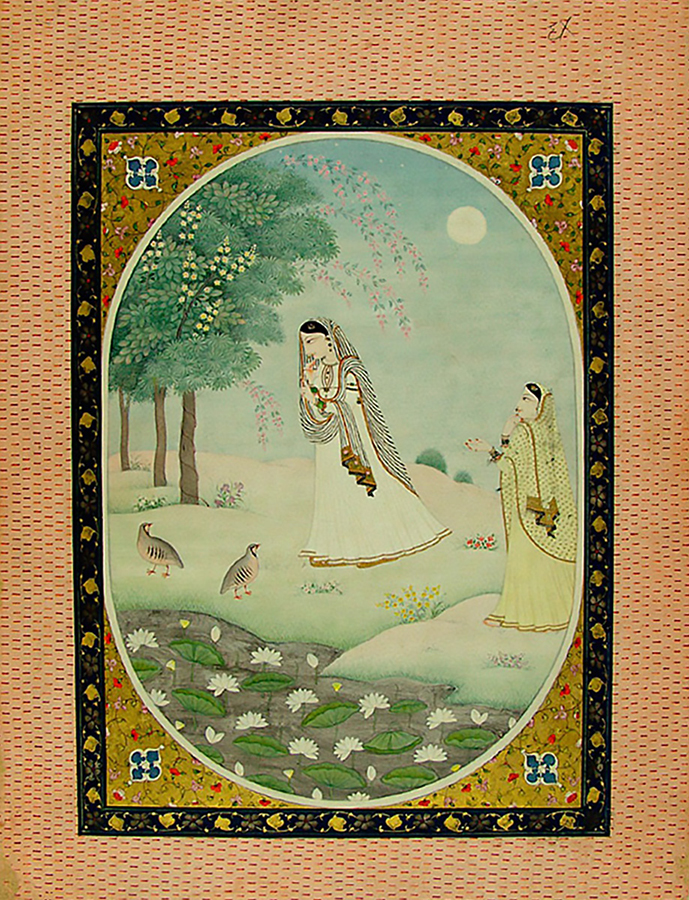

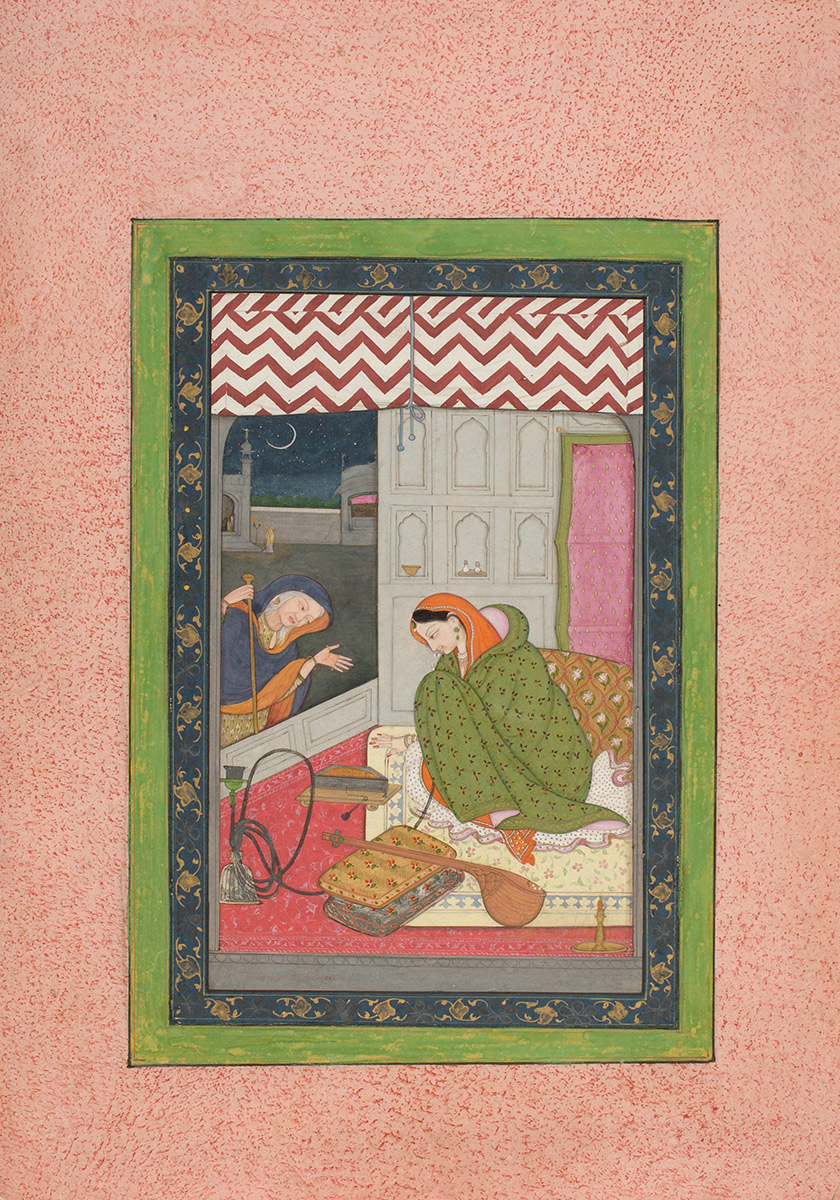

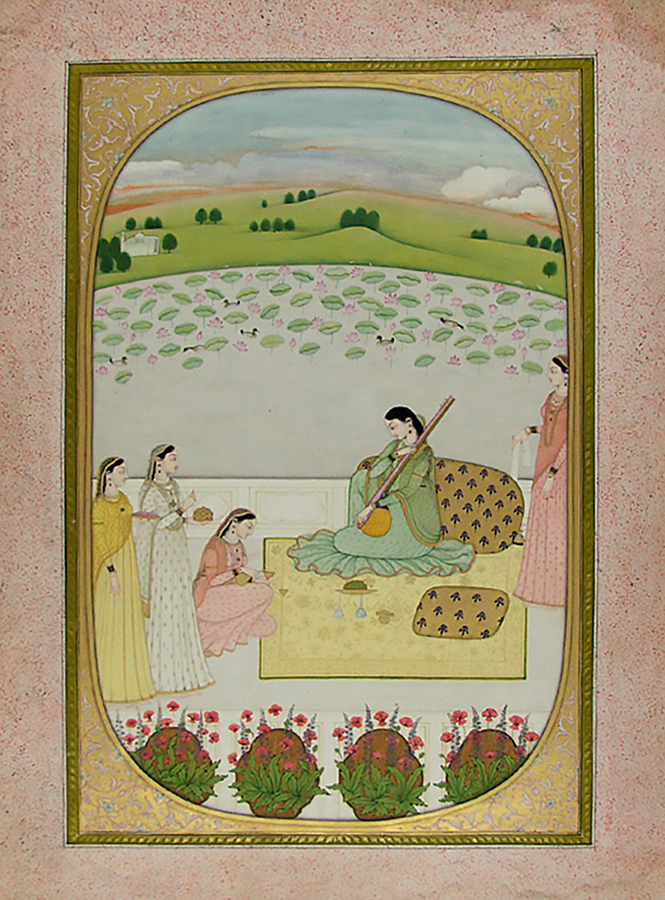

The Harvard Art Museums are fortunate to house luminous portraits of the Hindu heroines known as nayikas. Each figure’s attributes and emotions correspond to those of her absent lover, or nayaka (hero). Painted in the intricate Kangra style traditional to the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh, the works date to the 18th and 19th centuries.

A new installation of four portraits from this genre was curated by Rachel Parikh, the Calderwood Curatorial Fellow in South Asian Art. Featuring opaque watercolors on paper with added gold and silver details, the portraits represent archetypes of love, beauty, and romance. This is the first of two installations dedicated to the nayikas; a second will be on view this spring.

“These portraits show the lengths one would go for love,” said Parikh, who, in her installation, sought to highlight both the dreamlike, delicately detailed Kangra style as well as the tales of distress, deceit, and determination embodied in the portraits. “The emotions the heroines express—longing, anger, sadness—are relatable to anyone.”

Nayikas first appear in an ancient Sanskrit text on the performing arts, and they have inspired Indian classical dance, music, poetry, and art ever since. Paintings of the heroines are the best known and most widespread example of the Kangra style, characterized not only by a high degree of detail but also by refined coloring and a generally graceful manner. “They have a lyrical quality; you can feel the rhythmic sensation—the pulse of leaves against the background, the lily pads so beautifully executed with ducks weaving around them,” said Parikh. “Every time I look at these works, I find a new aspect to admire.”

Harvard’s nayika paintings were most likely once part of an album. “Clues from the framework and composition tell us that,” said Parikh, adding that even though the paintings may have been presented in the album format, they were meant to be viewed and appreciated as individual objects.

Another of the heroines on display in Parikh’s installation, the Abhisarika (Sanskrit for “beloved”) nayika, is pictured making her way into the woods at sunset while an attendant beseeches her not to. Despite the risk, she sets aside her modesty to brave the forest in pursuit of her lover. “The hand she holds up to her chin seems to indicate her awareness of the dangers that await her,” said Parikh.

Parikh hopes that by explaining narrative details and the types of nayikas represented, the installation will start a dialogue for visitors. And with these particular heroines, that conversation promises to be about the intoxicating, and often perilous, nature of love.