“Looking closely at an original drawing, ‘in the flesh,’ is a priceless experience,” said Edouard Kopp, who joined the Harvard Art Museums as the Maida and George Abrams Associate Curator of Drawings in Spring 2015. His belief also happens to be a core tenet of the museums’ own mission, and a concept at the heart of the two drawings exhibitions that the museums held this summer, Drawings from the Age of Bruegel, Rubens, and Rembrandt and Flowers of Evil: Symbolist Drawings, 1870–1910), and their related events.

Kopp recently answered a few questions about his passion for drawings and his hopes for teaching with the museums’ strong collection.

How did you develop your ability to study original drawings?

When I was a student at the Courtauld Institute in London, I took a course on the graphic arts in the Renaissance. As part of the class, we visited some of the great print rooms of England, including those in the British Museum, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, the Royal Library at Windsor Castle, and the Courtauld Gallery. This was a transformative experience for me, not only to see very high-quality drawings up close, but also to study and to discuss them with other students and with professors and curators. It made a world of difference.

What makes drawings unique as objects of study, compared to other art forms?

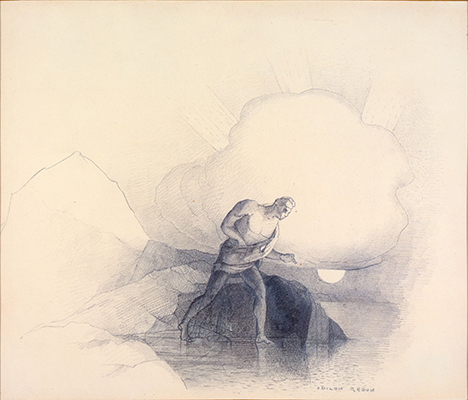

Drawings generally offer a sense of intimacy and immediacy. Also, they tend to be intriguing as objects, because they are often unfinished and rarely signed. So they make you ponder questions like why they were made and what they represent. You are urged to act like a detective and use the evidence that you have, thinking about ways to learn more about each drawing, the context(s) of its creation, and its use.

As a university institution, the Harvard Art Museums embrace close and sustained study of original works of art. How do we benefit from that approach when we look at drawings?

In many programs, especially in the United States, art history can be taught in a way that is quite theoretical. Our belief at the Harvard Art Museums is that the direct study of works of art is vital and cannot be replaced. There’s something very essential about the quality of a work of art that is tied to its materiality, its presence in three dimensions. When the work is in front of you, it forces you to be specific in the way you talk or write about it. We think it’s our duty as the repository of one of the finest drawings collections in the country—which encompasses European and American drawings from the 14th to the 21st century—to make these works on paper accessible. But it is our aim also to help the younger generation of students and scholars equip their gaze so that they know how to look at drawings, and how to learn and derive visual and intellectual pleasure from that experience.