Recently it seems that we’ve been swept down the rabbit hole and through the looking glass into a strangely upside down and backward world.

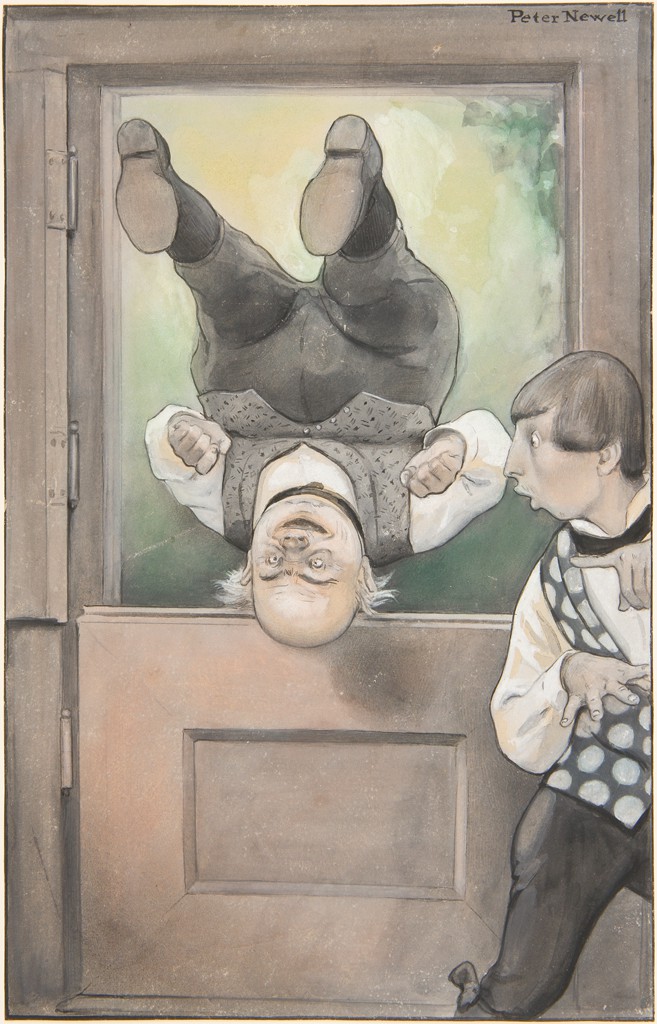

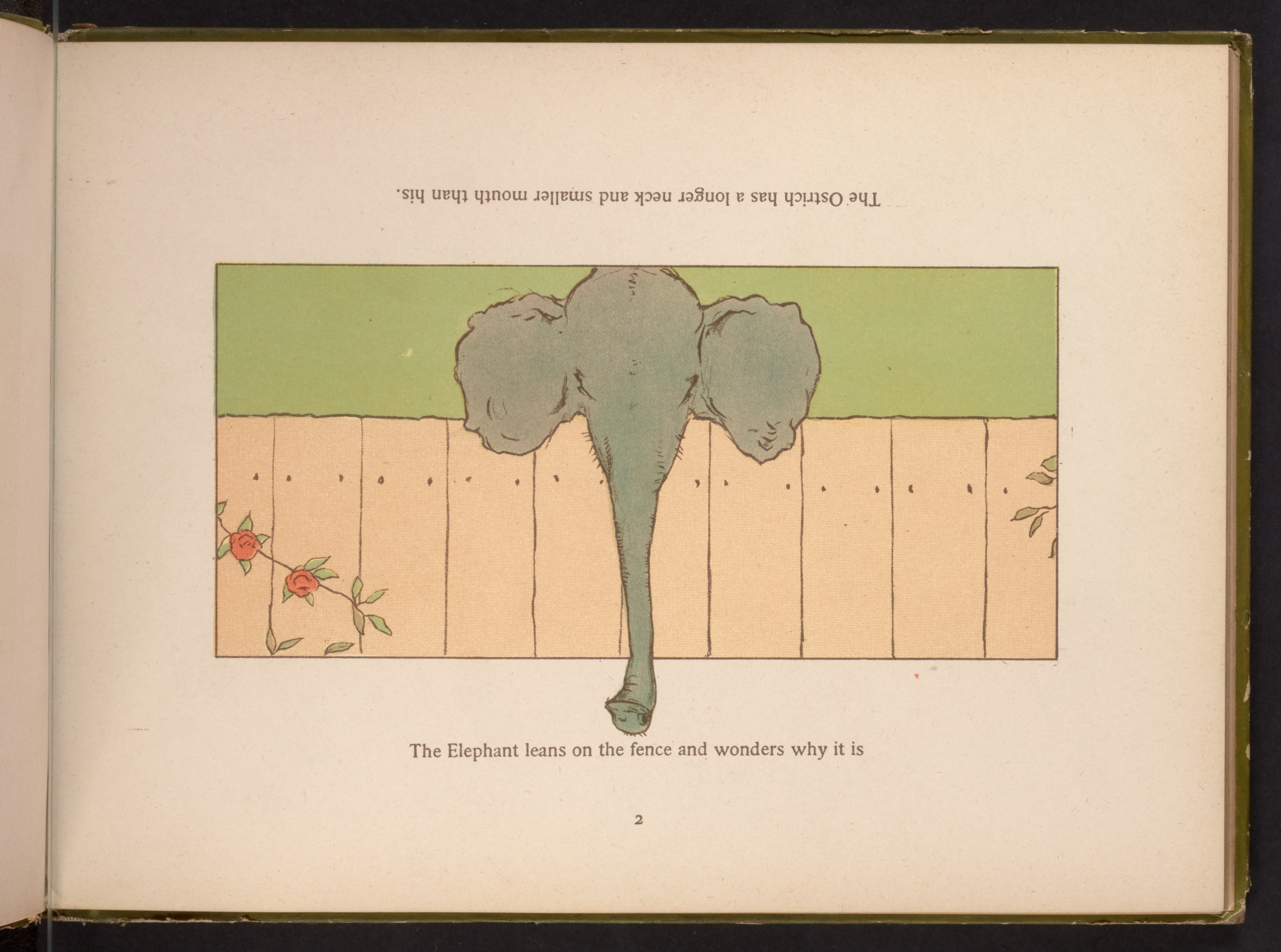

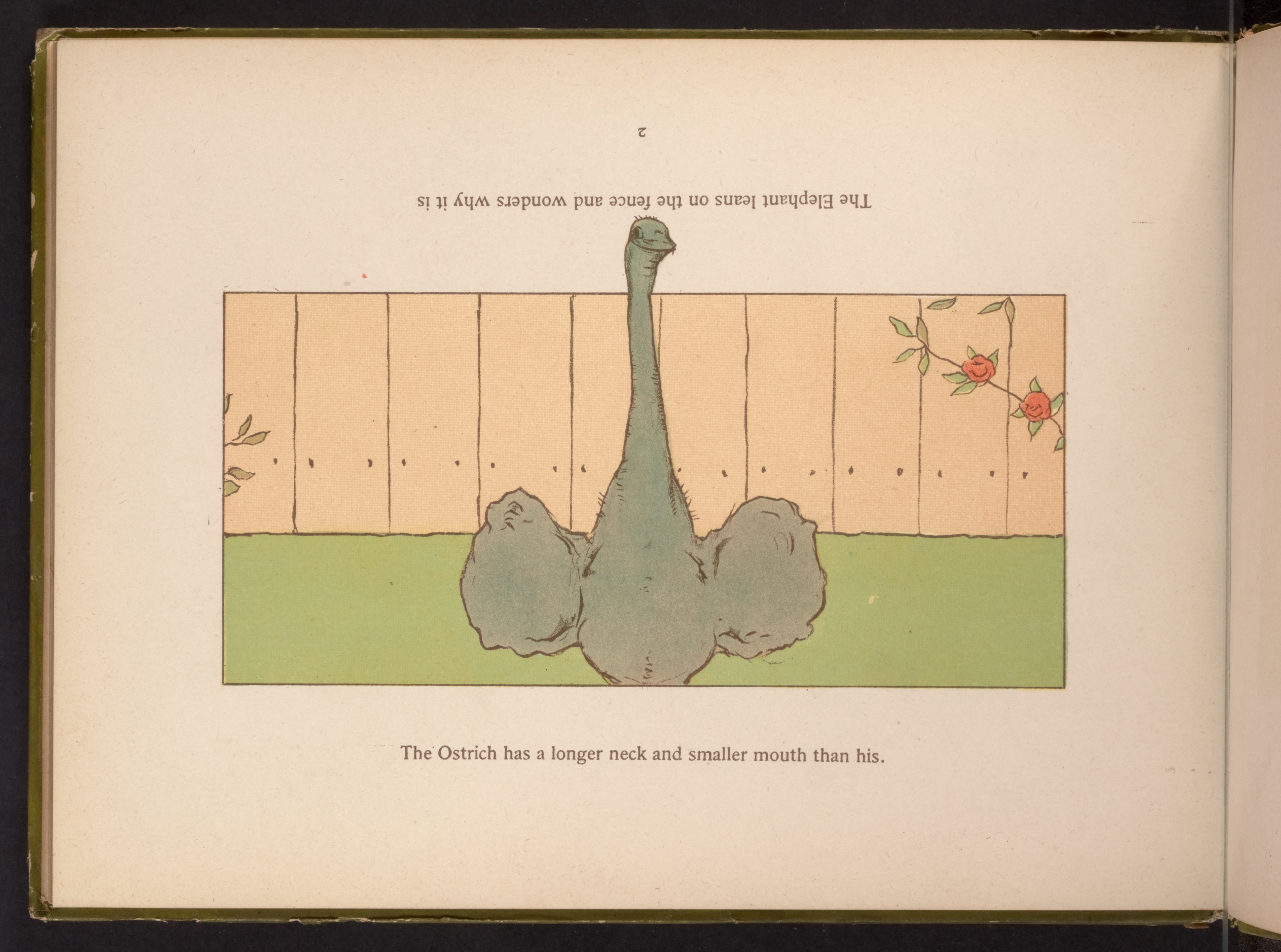

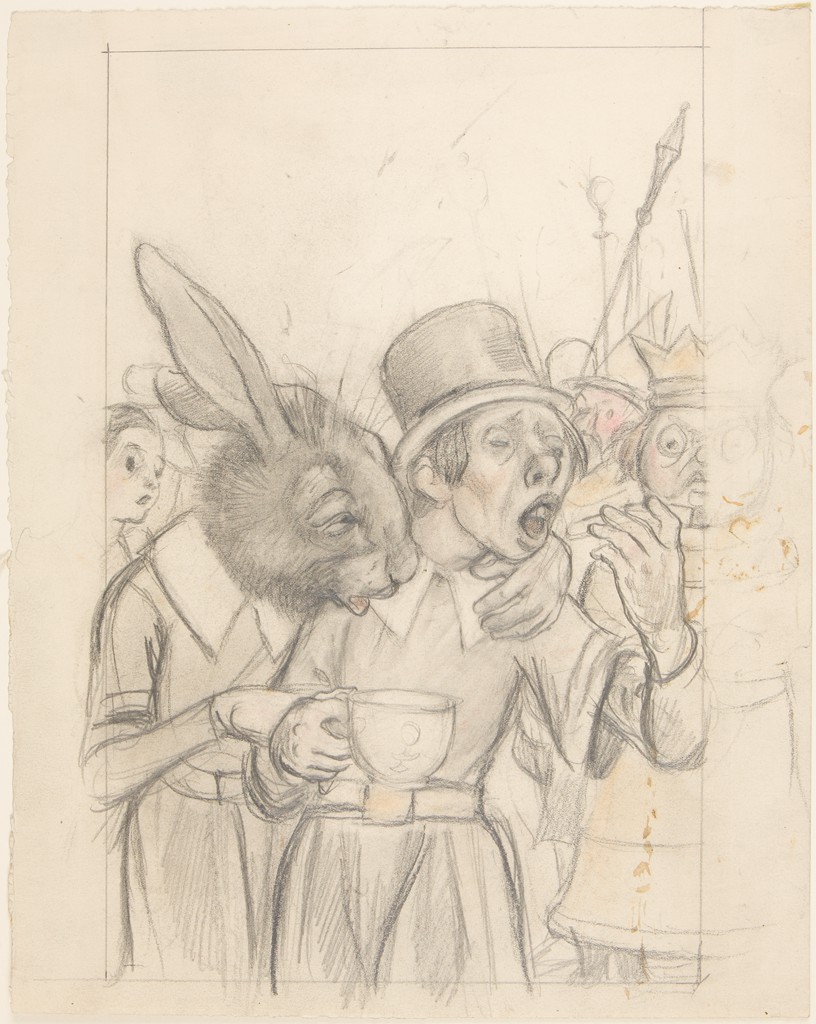

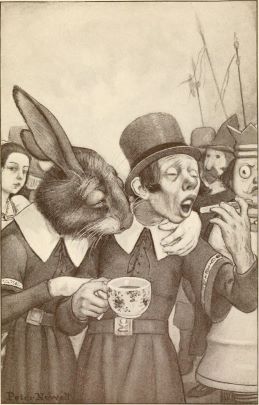

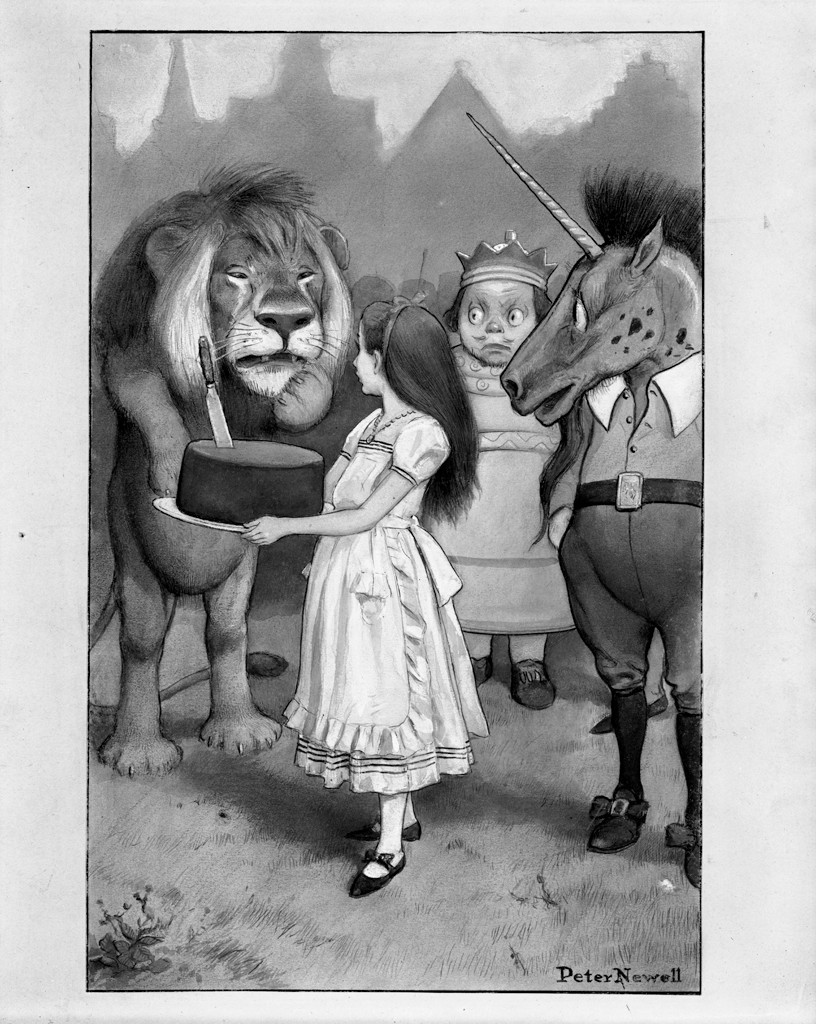

These figures of speech from Lewis Carroll’s beloved books Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There (1872) still resonate today, especially as we navigate unsettling times. The books’ indelible illustrations by John Tenniel (1820–1914) and subsequent attempts by his younger American counterpart, Peter Newell (1862–1924), are no less powerful. Indeed, Newell’s original drawings for Alice are among the most endearing works in the Harvard Art Museums collections. While Tenniel established the enduring visual identity for Alice and her companions, Newell reinvented Wonderland by exploiting advances in technology.

The relationship between text and image was foundational to Carroll’s creative expression from the start. The author had attempted to illustrate Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland himself but lamented that his drawings were too “crude.” In 1864, he engaged Tenniel, a prolific artist-illustrator whose anthropomorphic animals must have appealed to Carroll—his cartoons appeared frequently in the satirical magazine Punch, and he had illustrated a 19th-century edition of Aesop’s Fables. The manuscript for Alice did not provide extensive descriptions of the settings or characters, allowing Tenniel to create his own peculiar kingdom: “If you don’t know what a Gryphon is,” Carroll advised his readers, “look at the picture.”[1]

Tenniel’s Alice illustrations were produced as black-and-white wood engravings. His original graphite drawings were transferred onto woodblocks, which were in turn cut by professional engravers. At the time, wood engraving was the prevailing technique for illustration, and practitioners learned how to exploit the fine lines and often minute scale of the images so that their illustrations would be both legible and expressive of the text. Poet Austin Dobson celebrated the serendipitous marriage of Carroll’s text and Tenniel’s illustrations for Alice in 1907:

Enchanting Alice! Black-and-white

Has made your charm perennial;

And nought save “Chaos and old Night”

Can part you now from Tenniel.[2]