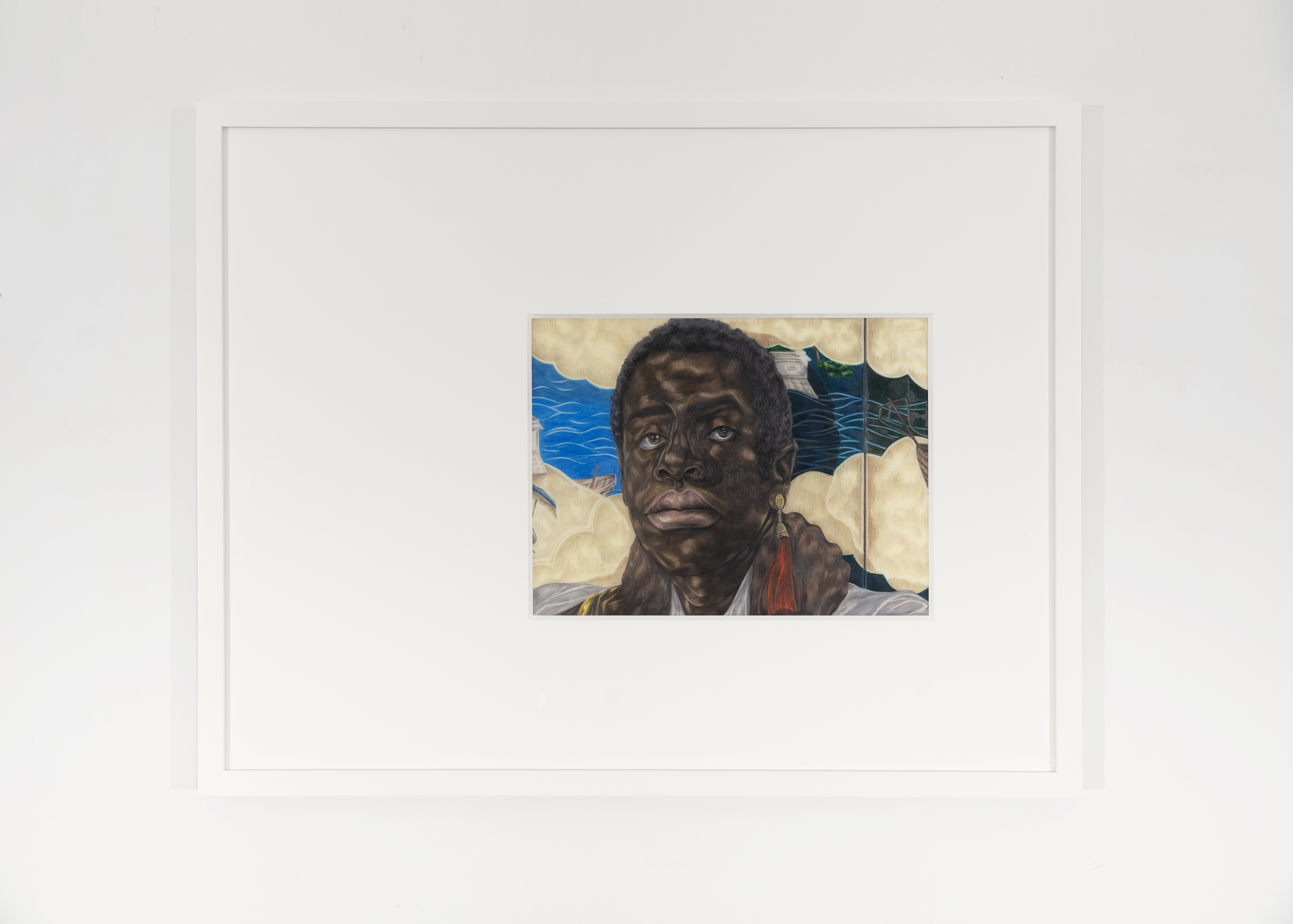

Considering Representation: On Elizabeth Catlett’s Portrait of a Woman

Beginning in the late 1940s, American and Mexican artist Elizabeth Catlett produced works at the Taller de Gráfica Popular (T.G.P.; the People’s Print Workshop) in Mexico City, including Cabeza de Negra (c. 1948), also known as Portrait of a Woman. While this print features an unnamed, unindividualized Black subject, Catlett produced portraits of many recognizable, public figures. In 1953 and 1954, for example, she led a collective print project at T.G.P. focused on celebrating prominent Black subjects, including Harriet Tubman, Paul Robeson, and Crispus Attucks.[1]

Prints such as Cabeza de Negra evidence Catlett’s complex negotiations of European modernism, including employing a critical stance to the embrace of cross-cultural modes of expression, and the intentional incorporation of T.G.P.’s longstanding sociopolitical, idiomatic work. From the 1930s, Catlett created lithographs and linocuts, which are printing techniques historically associated with radical, politically conscious artistic production. Her work was didactic, often seeking to elevate “ordinary” subjects for a working-class public. Perhaps unsurprisingly, by the 1950s, Catlett had caught the attention of anti-Communist forces. This scrutiny, combined with her work’s formal qualities and subject matter, gave Catlett a special status in 1960s visual culture and the Black Power imaginary.[2]

One of Catlett’s most recognizable and reproduced prints is Sharecropper (also named Cosechadora de algodón, or Cotton Picker, when published in 1957). First made while she worked out of T.G.P., the print shows an unnamed laborer. In Elizabeth Catlett: An American Artist in Mexico, Melanie Anne Herzog writes of the work:

This commanding image of a strong, dignified African American woman fieldworker is [a] superb example of the fusion of artistic languages that Catlett was able to employ to produce a powerful artistic statement. . . . Catlett claims an imposing presence for this obviously poor, hardworking woman who is seen from below, larger than life.[3]

Like the subject of Sharecropper, the Black woman in Cabeza de Negra is anonymous yet decidedly present, addressing the viewer directly and filling the frame. Fairly large for a single portrait image, the frame measures roughly 22 by 18 inches, and Catlett uses the entire surface to realize the image. The face, hair, and shoulders, which emerge from an indeterminate background, are executed in a series of maneuvers rendering light and dark areas, coalescing in a truly monumental portrait. The viewer can see the attention paid to materiality and process—a hallmark of Catlett’s practice.

Catlett’s oeuvre does the work of making “ordinary” figures consonant with well-known public figures. She represented both “ordinary” African American workers from the rural, southern United States and preeminent African American women. Her work was recognized as socially conscious by artists and revolutionaries of her time.[4] As Richard Powell puts it, “When one is face to face with Elizabeth Catlett’s graphic work, after celebrating her technical accomplishments and eye for visual eloquence, one must acknowledge, then marvel at, the inclusive, international dimensions of her subjects’ blackness, femaleness, and mejicanismo.”[5]

As evidenced in her body of work, Catlett remained committed to what I often think of as a keenly critical stance, engaging issues related to power and representation as well as perception and the gaze.

Chassidy Winestock is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History of Art and Architecture at Harvard University.

[1] Melanie Anne Herzog, Elizabeth Catlett: An American Artist in Mexico (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000), 101–3.

[2] Lisa Farrington, Creating Their Own Image: The History of African-American Women Artists (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 126–27; and Jo-Ann Morgan, The Black Arts Movement and The Black Panther Party in American Visual Culture (New York: Routledge, 2019), 47–49.

[3] Herzog, Elizabeth Catlett, 105.

[4] Farrington, Creating Their Own Image, 126–27; and Morgan, The Black Arts Movement, 47–49.

[5] Richard J. Powell, “Face to Face: Elizabeth Catlett’s Graphic Work,” in Elizabeth Catlett: Works on Paper, 1944–1992, ed. Jeanne Zeidler (Hampton, Va.: Hampton University Museum, 1993), 53.