Harvard alumnus Jesse Aron Green ’02 recently spoke to us about his exhibition Ärztliche Zimmergymnastik, on view in the University Galleries from May 23 to August 9, 2015.

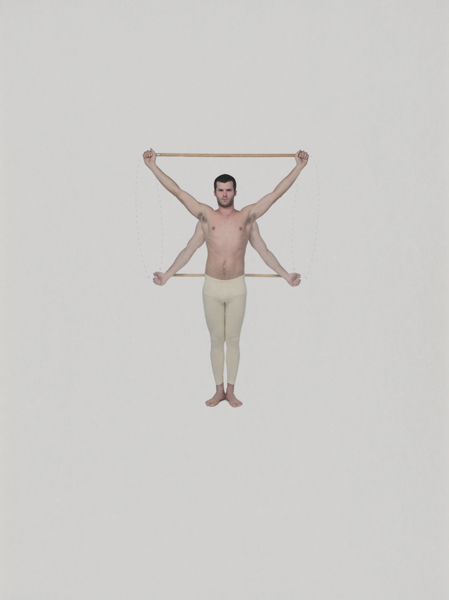

Green’s work investigates a range of interconnected themes: physical discipline, trauma, masculinity, and modernity, among others. In an 80-minute video installation titled Ärztliche Zimmergymnastik, 16 male performers use German doctor Daniel Gottlob Moritz Schreber’s 19th-century manual for the instruction of calisthenic exercises as a score for their movements. The video, together with associated photos, prints, and sculptures, elicits connections to contemporary art, including that of Sol LeWitt and Félix González-Torres.

Part one of our Q&A focused on how Green’s time at Harvard and his graduate education at UCLA shaped his art making. Here, he shares further insights into his work.

How would you describe the core meaning of Ärztliche Zimmergymnastik?

If you look closely at the video component of the Ärztliche Zimmergymnastik project, you’ll see a group of individuals doing the same set of exercises but in very different ways. Dr. Schreber may have wanted to invent a system that could bring about universal health and well-being, but even if we follow his directions to the letter, we can’t help but enact the ways that we are physically, psychologically, emotionally, and culturally different. For all of that difference, I am thankful.

Tell us more about the influences behind Ärztliche Zimmergymnastik.

Way before I started to make art, and way before I knew anything about art history, I loved looking closely at things—especially things that seemed simple, but got more complicated the closer you looked. Like noticing the tiny bump on a Lego that indicated where the two pieces of the mold that was used to make the piece fit together. At some point in graduate school, I started looking closely at the visual correspondence between the repetitive, serialized nature of bodies under the sway of totalitarian ideologies and sculpture from the late 1960s and ’70s (by Sol LeWitt, for example), which art historians organize under terms like “minimalism” and “conceptualism.” Fast forward to the culture wars of the 1990s, and you see artists like Félix González-Torres mobilizing similar systems of aesthetics—objects in piles or stacks or grids—to address the anxiety and melancholia around HIV/AIDS.

Ärztliche Zimmergymnastik was my attempt to organize these three examples of aesthetic similarity in a meaningful way. It’s a work of history.

Why does the work of Félix González-Torres resonate with you?

On April 16, 1995 (I remember because it was the day after Passover), my family visited the Guggenheim Museum in New York, which had just opened the first U.S. retrospective of González-Torres’s work. I was 15 years old, and I had never seen anything like it in an art museum before. Foil-wrapped candy heaped in glittering piles! Reams of posters on the floor—showing a single small bird in the middle of the sky, or the crumpled sheets of an unmade bed—that you could roll up and take with you! I remember it vividly, even if I didn’t understand it beyond the sense that these inexpensive, replaceable things—paper, candy—were symbols for something precious, requiring devotion and care.

Simultaneously, television—especially MTV—was starting to feature queer people in ways it hadn’t before. On The Real World: San Francisco, Pedro Zamora came out as gay and HIV-positive. His health began to decline before the end of the season, and he died shortly thereafter. Given the widespread fear of HIV/AIDS and the lack of support for queer youth (relative to what we have now), I took Zamora’s story to be one I would have to face, one way or another, directly or indirectly, in my own life. It invited a kind of projective melancholia.

I was struck with a similar feeling upon entering the González-Torres exhibition at the Guggenheim. I felt implicated by the work—like all great artwork, it called me into being. I took two candies from every pile, one to eat and one to keep. I took two posters from every stack, making sure to fold them with enough care so they would survive, unblemished, the trip back to Boston and whatever amount of time might elapse before I would unfold them, many years later.

What other early experiences with art left an impression on you?

As a kid I took drawing classes in the basement of Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts every Saturday morning. Afterward, my dad and I would share a croissant with marmalade in the museum cafe, then walk around and draw some more. The first contemporary art I remember seeing was there, on the wall across from where we would sit and eat: an LED ticker-tape with odd phrases scrolling by. I’ve since learned that it was one of Jenny Holzer’s first commissions by a museum, acquired in 1991. As an 11-year-old, I had no idea what it was about, but I knew it meant something. The best part is that it’s still hanging there, and it’s just as weird and enthralling to me now as it was then.

What advice do you have for viewers of your work, particularly if they are seeing it for the first time?

The best teachers I had at Harvard trained me to look as closely as possible, to challenge myself by asking simple, straightforward questions, and to answer those questions as precisely as I could.

When I’m in a gallery, regardless of whether I’m looking at a picture on a white wall or I’m at the center of an immersive installation, I ask myself: Where does the artwork position me, physically? Does its size or scale affect how I feel? How is it framed, both literally and figuratively? What is it made of? What does it remind me of from my own life? What does it recall from the history of art, or culture, or literature? Is the work discursive? Are my other senses engaged, and how? Where do I look, and why?