Artists have long pondered their professional identity and creative processes. In the 17th century, for instance, European artists like Velazquez and Rembrandt depicted themselves in their own works, sometimes in the act of painting.

A new temporary installation in the rococo and neoclassicism gallery, titled The Painter on Display, examines this self-reflective impulse. Consisting of both artists’ materials and works of art, the installation explores how artists enacted, perceived, and depicted aspects of their creative process.

“I’ve always been fascinated by representations of painters in their studios, how they portray themselves in relation to their art, and particularly how they use their art to meditate on the significance of being a painter,” said Lola Sanchez-Jauregui, the Maher Curatorial Fellow in American Art, who organized the rotation. “This installation gives us a chance to examine the painters’ profession and their perspective in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.”

The Artist’s View

In the works on display, artists serve as both subjects and authors. “They seek to answer the question, ‘What am I all about?’” Sanchez-Jauregui said. That sentiment is evident in François-André Vincent’s The Painter Apelles (1815), which depicts the renowned ancient Greek painter Apelles refusing the muses’ request to resume painting after he declared the work finished. In essence, Vincent makes a visual argument for an artist’s independent judgment in the creative process.

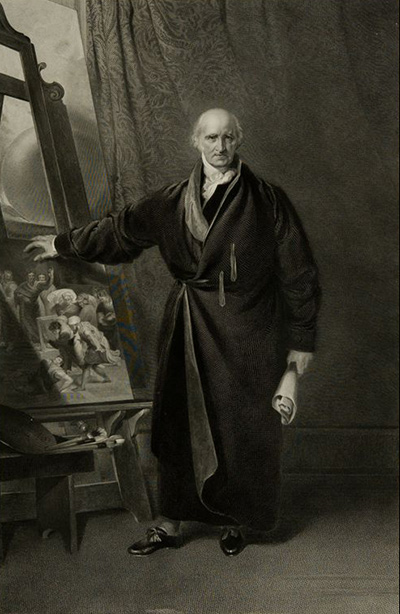

Charles Roll’s engraving Portrait of Benjamin West (1842) considers the question of the artist’s role in society by emphasizing West’s refined character. His gesture is serious, suggesting he has solid judgment, while his elegant dress—a full-length robe, sash, black suit, and shoes tied with ribbon bows—implies he is of a similar status to that of other prosperous individuals. Other artists were more cynical. One of Francisco de Goya’s plates in the album Los Caprichos (1797–98) portrays the artist as a trained monkey. That monkey is shown painting a donkey, which is disguised as a horse in a wig. The caption at the bottom of the engraving reads “Neither more nor less” (ni más ni menos)—a satirical representation of painters who seek only to please their patrons. (The work is particularly provocative in light of Goya’s own role as a royal painter for an unpopular king.)

James Gillray’s etching Titianus Redivivus (1797) casts a similarly critical eye on artists of the time, including Benjamin West, Robert Smirke, and John Hoppner. These artists were so eager to learn about and emulate the tones, materials, and methods of the Old Masters that they famously fell for a young woman’s claim that she could reveal secrets of Titian’s techniques—at a cost of 10 guineas.

The Artist’s Tools

Among the art materials on view is a chunk of lapis lazuli, a semiprecious gem found primarily in the Middle East that is one of the most expensive sources for ultramarine pigment in the world. Since ancient times, it’s been more treasured than gold, prized for the naturally brilliant blue hue it imparts to everything from jewelry to ornamental sculptures. European artists started using the pigment around the 14th century. (See the ultramarine in Fra Angelico’s Christ on the Cross, the Virgin, Saint John the Evangelist, and Cardinal Torquemada [c. 1453–54].)

Next to a vial of the powdered pigment is a late 18th- or early 19th-century animal-skin bladder. Bladders were precursors to the modern-day paint tube: artists would store their oil paints inside them and then seal them with string or ivory tacks to prevent the paints from drying out.

Though these types of objects were very familiar to artists of the past, they may surprise visitors today. The addition of the tools to the installation helps give a more holistic representation of how artists worked, said Sanchez-Jauregui.

“It’s important not to overlook this material side of painting,” said Sanchez-Jauregui. “I hope that viewing these tools will help people approach the paintings from a new point of view.”