What is the relationship between artistic expression and political action? This question has long occupied artists and was an enduring concern of American painter, photographer, and graphic artist Ben Shahn. With the 2020 elections fast approaching, Shahn’s work offers insight into the role art can play in advancing civic discourse.

In 1956, Shahn was asked to deliver the prestigious Charles Eliot Norton Lectures at Harvard. In one, he made the argument that a tendency toward nonconformity, which he defined as “a want of satisfaction with things as they are,” led artists to “become critics of society, and . . . partisans in its burning causes.” For evidence, Shahn urged the audience to look to the “passionate testament of their sympathies as it is written across the canvases and walls of the world.”

This is certainly true of Shahn’s oeuvre, which bears clear signs of his lifelong devotion to leftist politics. Many of his works are now in the collections of the Harvard Art Museums and Harvard’s Fine Arts Library, which jointly house the Ben Shahn Archive. The archive includes, among other works, Shahn’s drawings of the unfair trial and execution of anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti; his photographs capturing the plight of farm families during the Great Depression; and his posters protesting nuclear proliferation.

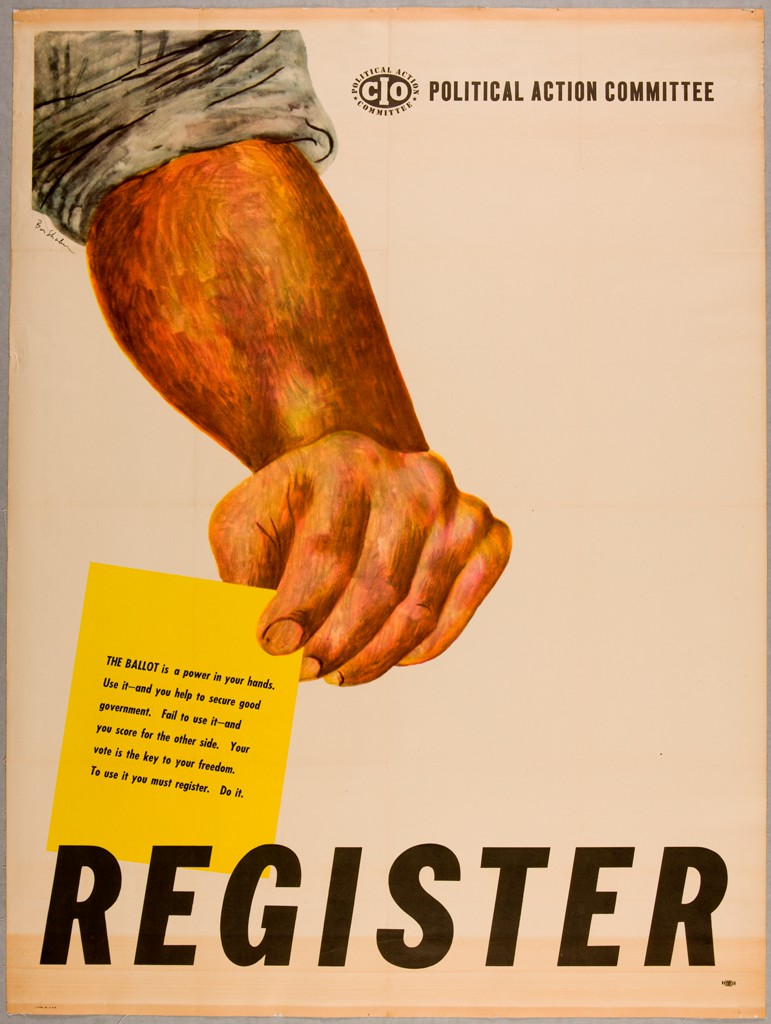

One of Shahn’s most direct engagements with politics came in the mid-1940s, when he was hired as chief artist of the Graphics Division for the newly created Political Action Committee (PAC) of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), a federation of labor unions. This was a fitting position for Shahn, who had participated in efforts to form an artists’ union in the mid-1930s and had produced posters for the Steelworkers Organizing Committee in 1936. While Shahn and his team of staff artists produced a wide array of graphic material for the CIO-PAC, his best-known works from this period are a series of posters he made in support of Franklin Roosevelt’s presidential reelection campaign in 1944. Hung in union halls across the country in the lead-up to the election, these posters called on the CIO’s five million members to vote for Roosevelt and his platform of progressive legislation.