In moments of crisis, art can communicate hope and a call to action. We looked at works from the collections that remind us to take a stance, build community, and make a difference.

Discussions of whether and how art can be an agent of political change have taken place over millennia and continue unabated today. Even the most protean creativity cannot exist outside of social, political, and economic frameworks. But not all art expressly acknowledges or engages with politics. What does it mean for art to be political? We aim to spark conversation about the responsibility not only of artists but of museums, too, which shape communities through access and interpretation. In his Notes of a Native Son (1955), James Baldwin writes that:

social affairs are not generally speaking the writer’s prime concern, whether they ought to be or not; it is absolutely necessary that he establish between himself and these affairs a distance which will allow, at least, for clarity, so that before he can look forward in any meaningful sense, he must first be allowed to take a long look back.

The following contributions are offered with Baldwin’s observation in mind.

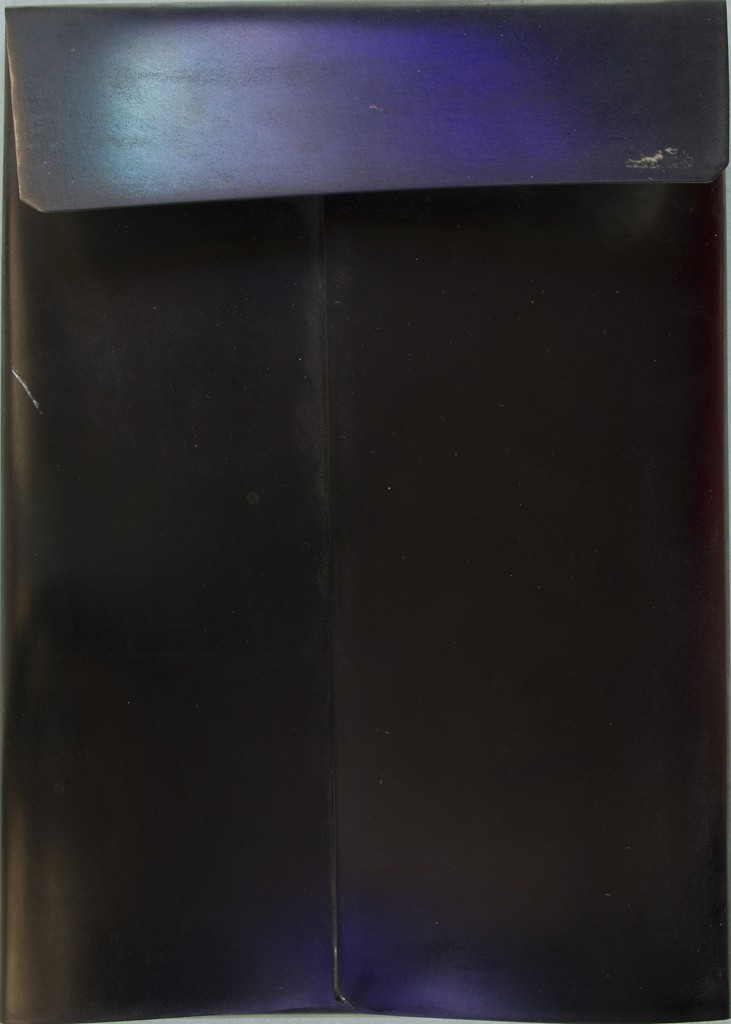

Posters for Peace

The image above is one of several prints made by Harvard students during the protests of April 1969. Chief among the protesters’ grievances was the university’s involvement in the Vietnam War, especially the creation of a Reserve Officers Training Corps on campus. A proliferation of posters expressing their pleas for change appeared across campus, and the greatest number came from a print shop set up in the basement of Memorial Hall by a group of students calling themselves Designers for Peace. An archive of 167 posters made during this period is housed in the Harvard University Archives, accessible for study and research.

Elizabeth M. Rudy, Carl A. Weyerhaeuser Associate Curator of Prints, Division of European and American Art