Three storied pieces of ecclesiastical silver from Salem, Massachusetts, have recently joined the Harvard Art Museums collections: a rare beaker (c. 1670) and two tankards (1690; 1759) are now prominently displayed in the museums’ Silver Cabinet. Used during communion, the silver vessels fulfilled a sacred ritual in Salem churches beginning in the 17th and 18th centuries, and survived a tumultuous period that included the Salem witch trials and the Revolutionary War. The three silver objects were presented to Harvard by Daniel and Susan Pollack (Harvard Class of 1960; Harvard Class of 1964).

Together, these pieces represent the work of three important Boston silversmiths who had been commissioned by three prominent Salem families. Daniel Pollack believes this church silver is “uniquely well suited to Harvard because of the fact that they are all Massachusetts pieces that were in Salem churches for over 300 years.” His hope is that they will remain together at Harvard, accessible to students, faculty, and visitors, for at least another 300 years.

Silver objects were frequently melted down and recast as coinage and other forms as fashions changed. The fact that these pieces survived intact for more than three centuries attests to their significance within their respective churches. Because of the metal’s association with purity and durability, silver objects played an important role in the Puritan church and religious rituals of many faiths. For Puritans, drinking wine (representing the blood of Christ) from shared beakers and tankards closely connected their service to the Lord’s Supper. Indeed, many patrons used silver vessels in their homes for several decades before presenting them to a church.

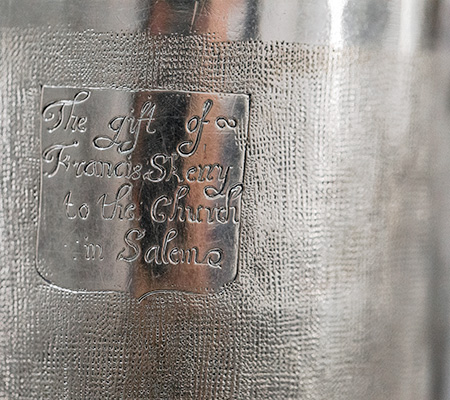

The Francis Skerry Beaker

The earliest vessel in the Pollack donation is a rare beaker with punched, fish-skin decoration made around 1670 by the first American-born silversmith, Jeremiah Dummer. In 1684, Francis Skerry, a major landowner in Salem, bequeathed the beaker, inscribed with his name, to the First Church of Salem, one of the oldest Protestant churches in North America.

From its placement on the communion table, the Skerry beaker witnessed the eventful years of 1692–93, when the First Church ministers and congregation were consumed by the infamous Salem witch trials. The First Church’s junior minister, Nicholas Noyes, was a vocal persecutor of the so-called witches, and two of the most famous accused victims, Rebecca Nurse and Giles Corey, were full members of the church.

Sometime in the 18th century, prominent double strap handles were added to the Skerry beaker and five other beakers, visually linking these half dozen vessels as a set. The handles facilitated the person-to-person passage of the vessel through the congregation during communion, emphasizing spiritual fellowship among church members.

The Benjamin Pickman and Clarke/Cabbott Tankards

Benjamin Pickman commissioned his tankard, made by Daniel Parker, for the First Church in 1759. A member of the “codfish aristocracy,” a group of merchants who made their fortune in the fishing industry, Pickman was an active patriot and chairman of the Committee to Protest the Stamp Act in 1765. The tankard features a rococo cartouche, a spiral twist (flame finial), and a handle with scroll thumbpiece; it was later transferred to Salem’s North Church, when it split from the First Church in 1772.

In 1784, the North Church received a second tankard from Elizabeth Clarke Cabott, the wife of Francis Cabott, a successful ship merchant. John Coney, the Boston silversmith who also made Harvard’s famous Stoughton Cup and the Holyoke Caudle Cup, crafted it around 1690. The tankard exemplifies the late 17th-century Boston Baroque style; a paired-dolphin thumbpiece ornaments the handle. It was not unusual for women to donate family silver to New England churches, and several women besides Elizabeth Clarke Cabott donated silver to both the First and North Churches.

“One is only a trustee of such pieces. They belong to the patrimony of this country.” –Daniel Pollack

Lasting Legacy

The First and North Church silver collections were recombined when the two churches reunited in 1923, and the First Church sold a portion of this historic silver in 2007 to meet the needs of its current community. The refined, elegant Puritan aesthetics of the beaker and two tankards as well as their historical interest appealed to Daniel Pollack, who collects 18th-century silver and 19th-century paintings.

When presenting these three silver vessels to Harvard, Pollack explained that his interest in collecting historic silver also lay in preserving the pieces for future generations. “One is only a trustee of such pieces,” Pollack said. “They belong to the patrimony of this country.” Thanks to the generosity of the Pollacks, the Harvard Art Museums are proud to be able to keep these significant pieces in New England and share them with visitors, students, and faculty for generations to come.

Laura Turner Igoe is the Maher Curatorial Fellow of American Art.