“It would of course be terribly interesting if you could find out anything about the photographer himself, what his background and working situation was, and what other work he might have done.”

So states a 1965 letter from John Szarkowski, director of the Museum of Modern Art’s Department of Photography, to curator Grace M. Mayer.[1] Szarkowski was sending Mayer to Hampton Institute (now Hampton University), in Virginia; her goal was to learn more about the photographer of 159 sumptuous platinum prints, which had recently been given to the museum, compiled in a leather-bound album. The trip proved fruitful—Mayer identified the photographer as Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864–1952), who had taken the photographs on Hampton’s campus between 1899 and 1900.

More than 50 years later, as a research assistant at MoMA, I found myself on a very similar mission: to find out more about the artist and the album itself, in preparation for a new publication on Johnston’s Hampton Album.

Quite a lot has been revealed about this extraordinary album since it was first given to MoMA by Lincoln Kirstein, who purchased the album in a bookstore in Washington, D.C., during World War II. At the turn of the century, Johnston had been commissioned to showcase the philosophies and activities of what was then called the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute. It was founded in 1868 to educate recently emancipated African Americans, and in 1878, the school began admitting Native Americans as well. The vast majority of Johnston’s images depict groups of students focused on their lessons, in classroom settings and outdoors. The photographs are a remarkable record of this unique educational moment in post-emancipation United States. By the time Johnston arrived at Hampton, her work had already been published nationwide, and she was operating a successful portrait studio in Washington, D.C. As a Washington Times reporter enthused, “Johnston is the only lady in the business of photography in the city, and in her skillful hands it has become an art that rivals the geniuses of the Old World.”[2]

Our research team at MoMA still had unanswered questions about the album, however: Who assembled it and when? What was the broader historical context? Could we uncover any other key characters in the story? Such questions meant that cross-collection research would be indispensable to this project, as we needed to see how MoMA’s prints compared to those at other institutions, and we were hopeful that a deep dive into archival correspondence would also help us piece together the puzzle. Our research team quickly realized that, in order to solve the remaining mysteries, we would need to visit each of the main repositories for Johnston’s images from this project: the Library of Congress, the Hampton University Archives, and the Social Museum Collection at the Harvard Art Museums.[3] Over the course of a few months, we visited each location, where we carefully sifted through hundreds of precious photographs and pored through even more correspondence. Along the way, we made discoveries that not only shed light on the album’s makers and historical context but also are relevant to issues of race and education today.

Our research team found out that a set of Johnston’s images from Hampton ended up at Harvard in the early 20th century, thanks to Francis Greenwood Peabody, founder of the Social Museum of Harvard University and a long-term trustee of Hampton. The Social Museum was considered to be the first attempt to “collect the social experience of the world as material for university teaching.”[4] In 1903, Peabody began gathering items for the collection, and Hampton Institute provided exactly the kind of “social experience” that Peabody wished to capture. On December 7, 1903, Peabody made this request of Hampton:

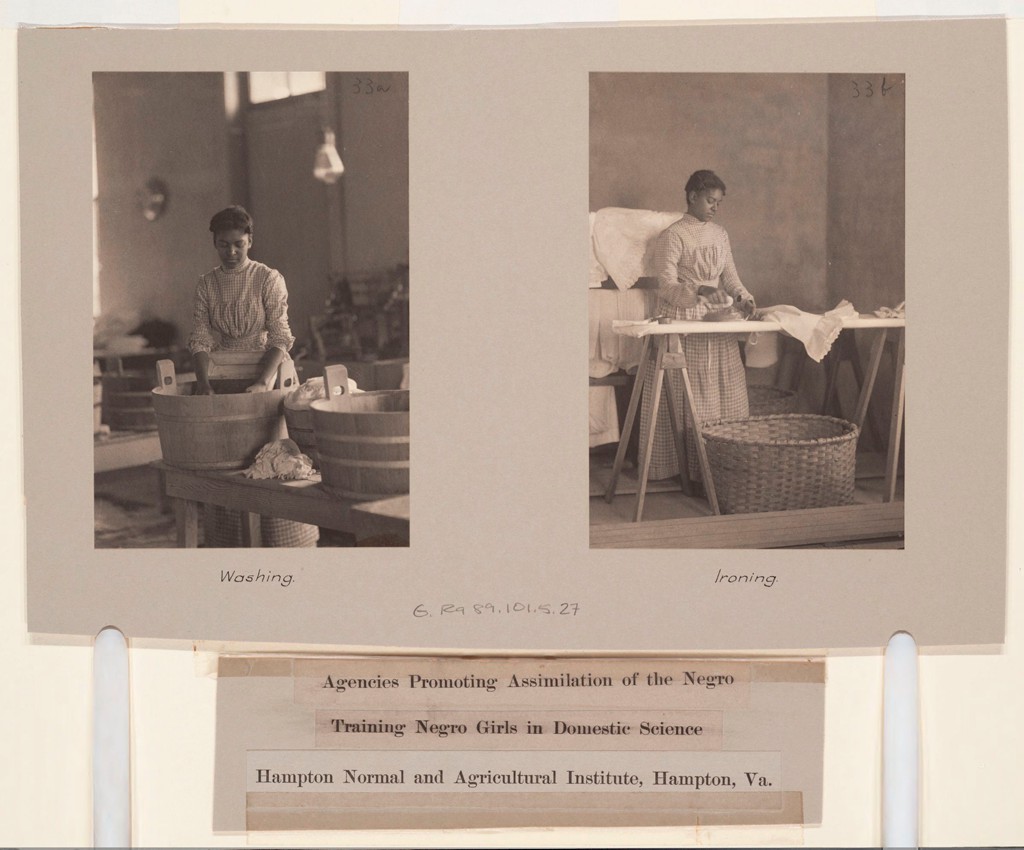

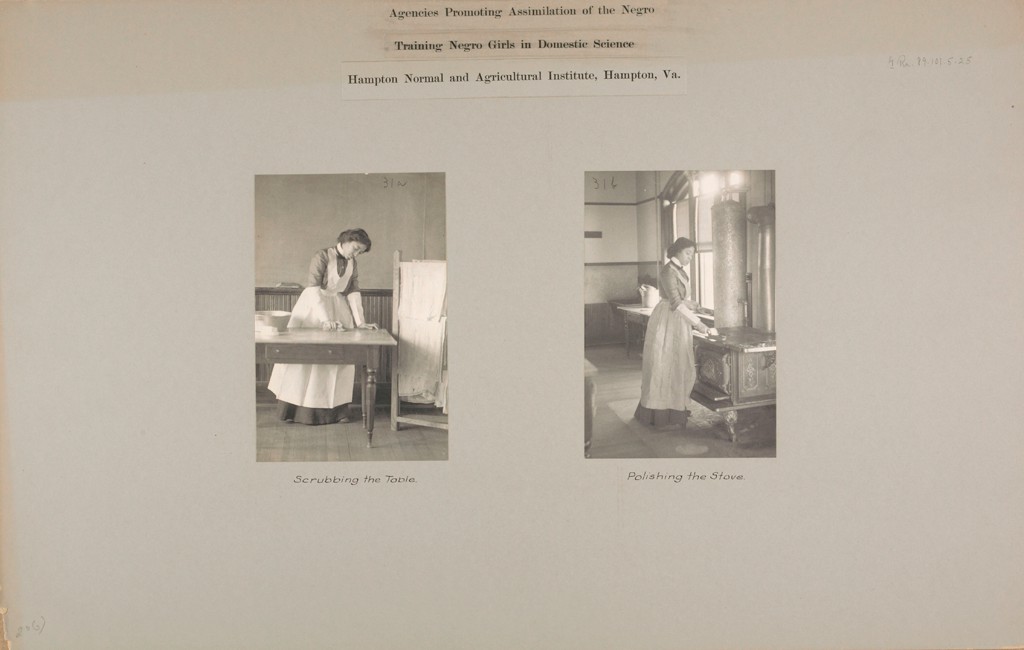

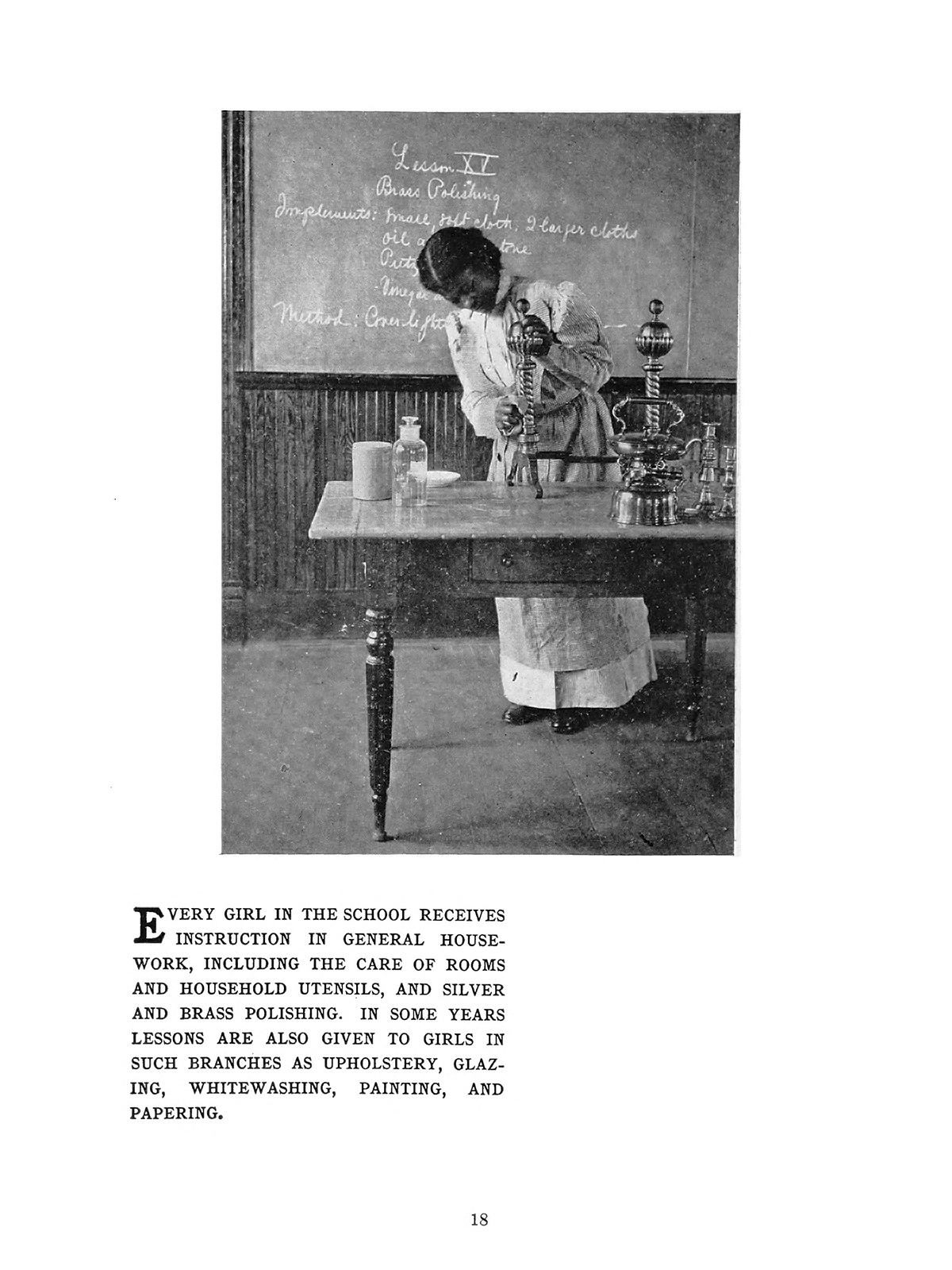

What we need is typical illustrations which would introduce a student to the subject, and permit him with the reports and literature to have the equivalent of a visit to the spot. All pictures of the nature of “before and after,” or practical class-room exercises and actual work, would be of special use.[5]

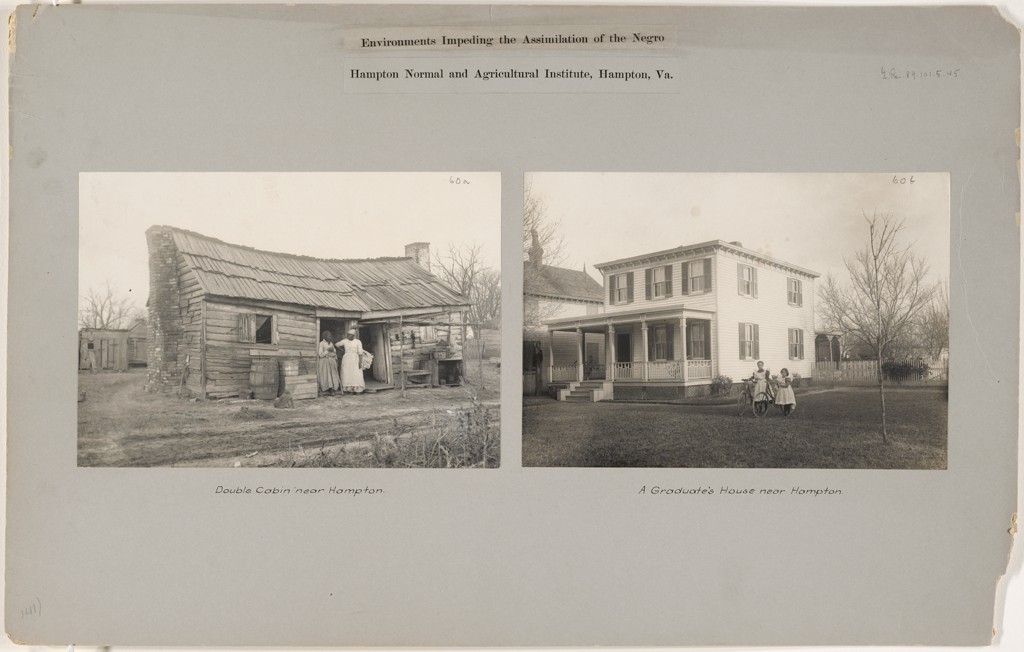

In a letter of January 12, 1904, he wrote, “I should not mix the ‘befores’ and ‘afters,’ but try to present a living and moving picture from primitive conditions to the best results. Let us have some personal contrasts also, as for instance an Indian arriving and an Indian departing.”[6] Scholar Julie K. Brown, contributor to the Harvard publication Instituting Reform: The Social Museum of Harvard University, 1903–1931 (related to an earlier exhibition and an online Special Collection), discusses these comparisons, which present troubling aspects ingrained in social reform of that era, such as the desire to “civilize” African and Native Americans.[7] MoMA’s research initiative further pursued how Hampton Institute’s educational philosophy influenced its approach to these issues.