On a visit to the museums’ storeroom, curator Susanne Ebbinghaus took a closer look at an ancient amphora. The sturdy, sizable vessel was covered in accretions from being buried for millennia, further disfigured by earlier restorations and missing its base. For Index, Ebbinghaus and conservation fellow Haddon Dine share how they got the object back into shape and what they learned in the process.

During her first encounter with the object in the storeroom, Ebbinghaus was immediately intrigued by this vessel, which had entered the museums’ collections a century earlier. The amphora’s form is unusual for this type, especially how its handles project from its shoulders. The decoration consists of two bands of impressed, repeating figures that appeared to include horses and a rider, but the surface was too dirty to be sure. Clearly, the jar had potential to be a striking display piece in the galleries—after some long overdue TLC—so it was brought to conservation fellow Haddon Dine in the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies for further examination and treatment.

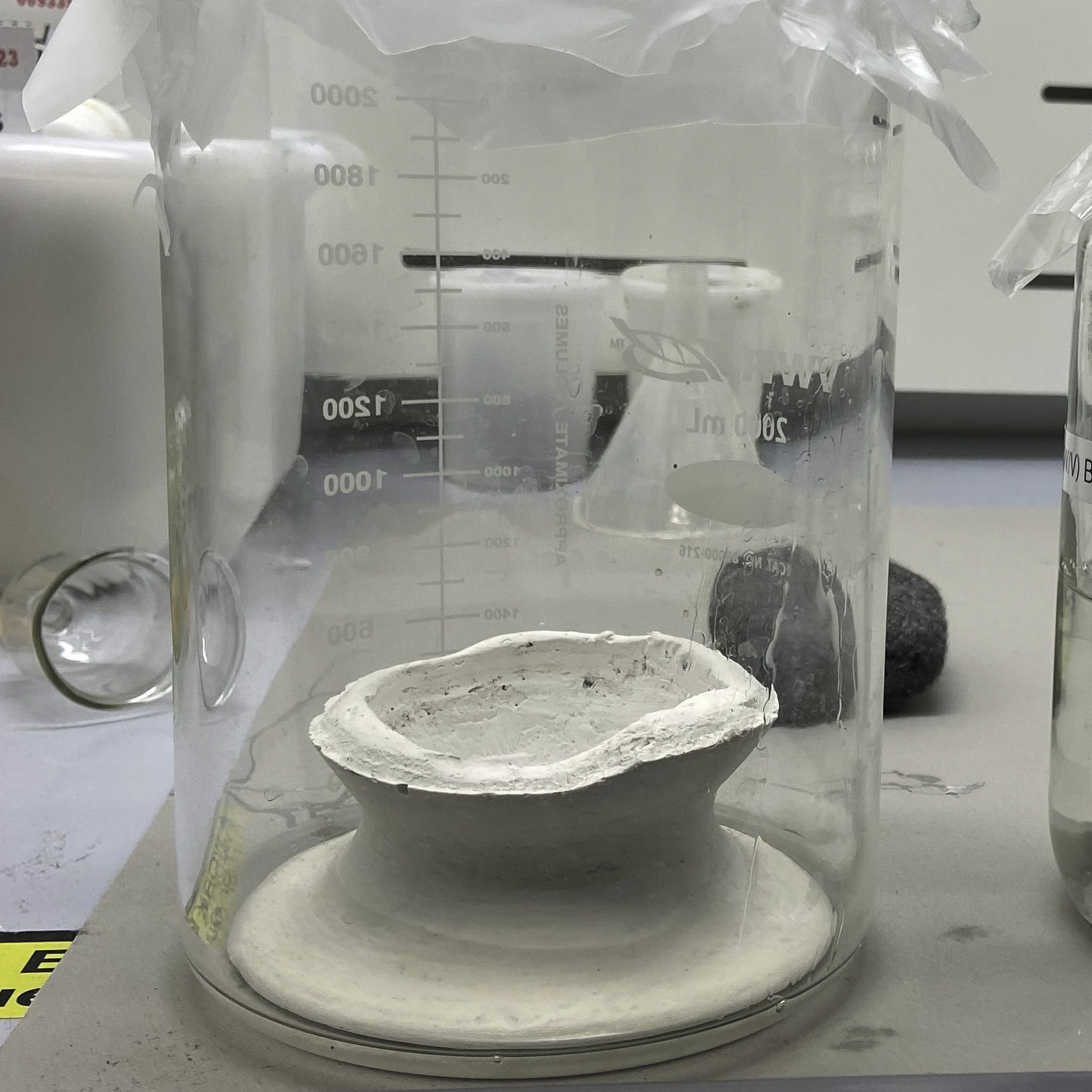

Dine scrutinized and documented the amphora in the Objects Lab, then we identified treatment goals together. These included cleaning the exterior, replacing the unsightly old restorations, and stabilizing cracks. But we also decided to “resurrect” the vessel and enable it to stand again. As it turned out, making a new base was not a straightforward process. It would require considerable discussion, work and re-working, as well as research. That research would ultimately lead to discoveries not just about the amphora but about other objects in the collections, as well.