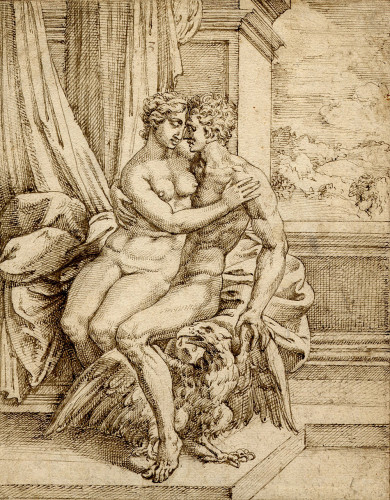

1982.50: The Brazen Serpent

DrawingsA crowd of nude figures lies on rocky ground. In the foreground, a man with contorted limbs has snakes wrapped around each arm. His face is pained and his mouth is open. Children lie in front of him. A male figure and female figure behind him face backward at another group of snakes crawling toward the foreground. The man’s back is to the viewer, but the woman’s face has a horrified expression. Three more figures crouch and cover their heads in the right background.

Identification and Creation

- Object Number

- 1982.50

- People

-

Michiel Coxcie, Netherlandish (Mechelen 1499 - 1592 Mechelen)

- Title

- The Brazen Serpent

- Classification

- Drawings

- Work Type

- drawing

- Date

- c. 1533-39

- Culture

- Netherlandish

- Persistent Link

- https://hvrd.art/o/294921

Physical Descriptions

- Medium

- Brown ink over black chalk on light tan antique laid paper

- Dimensions

-

20.7 x 32.8 cm (8 1/8 x 12 15/16 in.)

mount: 29.1 x 41.2 cm (11 7/16 x 16 1/4 in.) - Inscriptions and Marks

-

- collector's mark: lower left, black ink, stamp: L. 628 (Richard Cosway)

- collector's mark: lower left, brown ink, pen: L. 1433, variant (John C. Robinson)

- blind stamp: lower left, blind stamp: L. 2445 (Thomas Lawrence)

- inscription: mount, lower left, graphite: 7 Michael Coxis

- inscription: mount, lower right, graphite: Cosway + Lawrence

- inscription: mount, verso, center, graphite: Michael Coxie / Cosway + Lawrence

- inscription: mount, verso, lower left, graphite: 16

- inscription: mount, verso, lower right, black ink: 11

- watermark: A bishop’s hat; closely related to Briquet 4969 (Colmar, 1531)

Provenance

- Recorded Ownership History

-

Richard Cosway, Esq., London (L. 628, lower left), probably sold; [G. Stanley, London, 14 21 February 1822, perhaps either lot 172 (as Heemskerk), lot 347 (as Bandinelli), or lot 572 (as Michelangelo)]. Sir Thomas Lawrence, London (L. 2445, lower left). [1] Possibly Samuel Woodburn, London, sold; [Christie’s, London, 20 June 1854, lot 794 (as Coxie, "The Deluge")]. Sir J. C. Robinson, London (L. 1433, variant, lower left), sold; [Christie's, London, 12 May 1902, lot 95]; to [F. J. Parsons, London.] Frederick N. Price (president of Ferargil Galleries), New York, given; to Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, Penn., 1933-41 (inv. no. 403), deaccessioned; to [James A. Bergquist, Boston] sold; to Fogg Art Museum, 1982; Curatorial Study Group Fund, Marian H. Phinney Fund, William C. Heilman Fund and Paul J. Sachs Memorial Fund, 1982.50.

1. The drawing is not known in Lawrence's sales of 1830, 1831, or 1860, nor is it in his inventory housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Published Text

- Catalogue

- Drawings from the Age of Bruegel, Rubens, and Rembrandt: Highlights from the Collection of the Harvard Art Museums

- Authors

- William W. Robinson and Susan Anderson

- Publisher

- Harvard Art Museums (Cambridge, MA, 2016)

Catalogue entry no. 20 by William W. Robinson:

In Giorgio Vasari’s succinct formulation, it was Michiel Coxcie “who brought to Flanders the Italian manner.”1 During an artistic career that spanned more than six decades, Coxcie played a major role in introducing Italian High Renaissance style into the pictorial arts of the Netherlands. According to artist–biographer Karel van Mander (1548–1606; 2001.135), Coxcie studied with Bernard van Orley (2002.22) .2 He probably arrived in Rome in the late 1520s, and about 1531 the Dutch cardinal Willem van Enckenvoirt commissioned him to paint frescoes with scenes from the life of Saint Barbara in the Church of Santa Maria dell’Anima. These impressed Vasari for “imitating very well our Italian manner.”3 Enckenvoirt also supported Maarten van Heemskerck (1994.155), whose sojourn in Rome coincided with Coxcie’s. Like Heemskerck, Coxcie studied the works of Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Michelangelo, and Giulio Romano, as well as the sculpture and architectural remains of ancient Rome.4 Back in the Netherlands by 1539, Coxcie worked primarily in Brussels but also fulfilled commissions from churches in Mechelen and Antwerp. In addition to painting altarpieces, devotional pictures, and portraits, he designed prints, tapestries, and stained glass. In the 1540s, Coxcie provided the cartoons for monumental windows donated by members of the imperial family to the Brussels church of Saint Gudule. He served as court painter to Mary of Hungary, regent of the Netherlands, and also worked for her brother, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, and Charles’s son, King Philip II of Spain.5

The Harvard drawing illustrates a passage from the Book of Numbers (21:5–9). Weary from their journey in the wilderness near the Red Sea, the Israelites “spoke against God and against Moses.” The Lord sent fiery serpents that bit and killed many of the people. When they repented, Moses, following the Lord’s direction, “made a serpent of brass, and put it upon a pole, and it came to pass, that if a serpent had bitten any man, and he beheld the serpent of brass, he lived.”6 The drawing shows only the serpents attacking the people, but it has been cut down from a larger composition and, like Coxcie’s print of this subject (Fig. 1), might originally have included more of the narrative.7

The traditional attribution to Coxcie of the Brazen Serpent, documented by inscriptions on its mount, is sustained by comparison with a series of ten drawings in the British Museum that illustrate the Loves of Jupiter. Three of these bear Coxcie’s monogram, and all ten were reproduced in reverse in engravings by an unidentified printmaker.8 As Molly Faries observed in her 1975 publication on the Harvard sheet, the systematic parallel and cross-hatched pen lines that model the figures are virtually identical to the disciplined strokes in the Loves of Jupiter drawings (Fig. 2).9 The contours and handling of details such as hands, feet, hair, and musculature are also closely comparable. The affinity of its technique to that of the Loves of Jupiter not only confirms the attribution of the Harvard sheet, but also suggests a date for it during the same period as the designs for the print series. Faries convincingly assigned the Harvard composition and the Loves of Jupiter to Coxcie’s Roman years.10 She further related the drawing to Coxcie’s only autograph print, an etching, later reinforced with etching and burin, that also represents The Brazen Serpent (see Fig. 1).11 The print is signed Mighel Flamingo inventur, an Italianate form of his name that implies its publication in Rome.12 None of the elements in the etching and drawing correspond exactly, so the Harvard work is not a direct study for the print, but a variant composition.13

Coxcie’s Roman works, with their complex poses, idealized musculature and proportions, and exalted facial expressions, register the impact of antique and Italian models—particularly works by Michelangelo—on his early development.14 As Faries observed, the figure seen from the back at the upper left of the drawing was inspired by the Hellenistic sculptural fragment known as the Belvedere Torso, while the pose of the terrified man with drawn-up legs next to him derives from the Deluge on the Sistine ceiling. Most conspicuously, the outstretched, heroically suffering male figures at the center of the Harvard work and lower right of the Brazen Serpent etching were adapted from Michelangelo’s Tityos, one of the drawings the Italian master made in 1532–33 for Tommaso de’ Cavalieri.15

Notes

1 “che portò in Fiandra la maniera italiana”; Karel van Mander and ed. and trans. Hessel Miedema, The Lives of the Illustrious Netherlandish and German Painters, from the First Edition of the Schilder-boeck (1603–04) (Doornspijk, Netherlands 1994–99), vol. 4, p. 185 (n. 20).

2 Ibid., vol. 1, pp. 292–94, and vol. 4, p. 184; Koenraad Jonckheere and Ruben Suykerbuyk in Koenraad Jonckheere, ed., Michiel Coxcie 1499–1592 and the Giants of His Age (London and Turnhout, 2013), pp. 24–25. My thanks to Ruben Suykerbuyk for his comments on a draft of this entry.

3 “imitando molto bene la maniera nostra d’Italia”; Van Mander/Miedema, vol. 4, p. 186 (n. 29). Coxcie completed the frescoes by 1534; Koenraad Jonckheere, Ruben Suykerbuyk, and Eckhard Leuschner in Jonckheere et al., pp. 26–27 and 53–63. A preparatory drawing for one of them was published by Achim Gnann and Domenico Laurenza, “Raphael’s Influence on Michiel Coxcie: Two New Drawings and a Painting,” Master Drawings, vol. 34, no. 3 (Fall 1996): 293–302, pp. 294–98, repr. fig. 5.

4 Jonckheere in Jonckheere et al. 2013, pp. 66–97.

5 Bob van den Boogert, “Habsburgs imperialisme en de verspreiding van renaissancevormen in de Nederlanden: De vensters van Michiel Coxcie in de Sint-Goedele te Brussel,” Oud Holland, vol. 106, no. 2 (1992): 57–80, pp. 60–72 and 76; Van Mander/Miedema, vol. 4, pp. 182–91; Almudena Pérez de Tudela and Melina Reintjens in Jonckheere et al., pp. 100–115 and 140–55.

6 See Faries 1975, pp. 137– 38, on the popularity and significance of the subject during the sixteenth century.

7 See below, notes 11 and 12, for the print.

8 London, British Museum, 1861,0112.1–10. Arthur Ewart Popham, Dutch and Flemish Drawings of the XV and XVI Centuries, Vol. 5 in Catalogue of Drawings by Dutch and Flemish Artists Preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum (London, 1932), [Coxcie], nos. 1–10, pp. 12–14; Koenraad Jonckheere and Joris van Grieken in Jonckheere et al. 2013, pp. 87–91 and 164–70. Nine of the ten drawings are executed in brown ink. One, Jupiter in the Form of Diana, Enjoying Callisto (1861,0112.10), is in black chalk. A set of the engravings is in the British Museum, 1925,1117.150–159, where they are attributed to the School of Marcantonio Raimondi. However, the traditional attribution of the prints to Cornelis Bos has recently been reconsidered; Joris van Grieken in Jonckheere et al. 2013, pp. 169–70. Virgil Solis engraved copies of seven of the prints (Hollstein, vol. 63, nos. 221–27, pp. 180– 83).

9 Molly Faries, “A Drawing of the Brazen Serpent by Michiel Coxie,” Revue Belge d’Archeologie et d’Histoire de l’Art, vol. 44 (1975): 131–41, pp. 131–35. Jupiter, in the Form of Amphitryon, with Alcmena Seated on His Lap (Fig. 2) is in brown ink; incised. 173 × 136 mm. London, British Museum, 1861,0112.3. Popham [Coxcie], no. 3, p. 13.

10 Faries, pp. 133–36. Joris van Grieken in Jonckheere et al., pp. 164 and 181 (n. 43), also dated the drawings for The Loves of Jupiter to Coxcie’s Roman period, although he proposes (pp. 169–70) that the prints might have been produced after Coxcie returned to the Netherlands in 1539.

11 Faries, pp. 133–36. Michiel Coxcie, The Brazen Serpent (Fig. 1). Etching and engraving. 297 × 428 mm. Cambridge, Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, G9083. Hollstein, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 62. Edward Wouk in New Hollstein, Frans Floris, part 1, pp. l–li.

12 Konrad Oberhuber, Die Kunst der Graphik IV. Zwischen Renaissance und Barock: Das Zeitalter von Bruegel und Bellange (Vienna: Graphische Sammlung Albertina), p. 89; Faries, pp. 136–37; Domenico Laurenza, on p. 112 of “Michel Coxcie à Rome et dans les Pays-Bas anciens: Nouvelles attributions,” in Eugeen Van Autenboer, Yvette vanden Bemden, Bob C. van den Boogert, et al., Michel Coxcie: Pictor regis, 1499–1592 (International colloquium, Mechelen, 5–6 June 1992, published as one issue of Handelingen van de Koninklijke Kring voor Oudheidkunde, Letteren en Kunst van Mechelen (Mechelen, Belgium 1993), vol. 92, no. 2, 93–117), and again on pp. 30-31 of “Un Dessin de Giulio Clovio (1498–1578) d’après Michel Coxcie (1499–1592): De l’influence de Raphaël et de Michel-Ange sur des artistes de la génération de 1530,” Revue du Louvre, vol. 43, no. 3 (June 1994): 30–35, all dated the print to Coxcie’s Roman sojourn. Nicole Dacos, “Michiel Coxcie et les romanistes: A propos de quelques inédits,” in Van Autenboer et al.: 55–92, p. 78, dated the print after Coxcie returned to the Netherlands, citing the derivation of three figures in the print from Van Orley’s Crucifixion in Bruges, but the comparison is not compelling. More recently, Joris van Grieken also argued that Coxcie could have produced the Brazen Serpent print soon after he returned to the Netherlands in 1539; Joris van Grieken in Jonckheere et al., pp. 171–73.

13 Faries, p. 136, concluded, “The drawing . . . is most likely a study related to the print in the sense that it represents an alternate composition.” Karel G. Boon, The Netherlandish and German Drawings of the XVth and XVIth Centuries of the Frits Lugt Collection (Paris, 1992), vol. 1, under cat. 61, p. 104, also regarded the drawing as a study for the print. Dacos, p. 78, dated the print later than the drawing, although she did not provide an argument for her dating.

14 Faries, p. 136; Laurenza (1994), pp. 30–31.

15 Faries, pp. 136–37. Faries also noted that Coxcie’s Rape of Ganymede in the Loves of Jupiter series is based on Michelangelo’s drawing of this subject, another gift to Tommaso de’ Cavalieri in 1532. For Michelangelo’s drawings for Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, see Stephanie Buck in Stephanie Buck et al., Michelangelo’s Dream (London: The Courtauld Gallery, 2010), cats. 2–8, pp. 110–45.

Figures

Acquisition and Rights

- Credit Line

- Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Curatorial Study Group Fund, and the Marian H. Phinney, William C. Heilman and Paul J. Sachs Memorial Funds

- Accession Year

- 1982

- Object Number

- 1982.50

- Division

- European and American Art

- Contact

- am_europeanamerican@harvard.edu

- Permissions

-

The Harvard Art Museums encourage the use of images found on this website for personal, noncommercial use, including educational and scholarly purposes. To request a higher resolution file of this image, please submit an online request.

Publication History

- Molly Faries, "Swathmore's 'Underground' Art Collection", Bulletin Swathmore College (1971), December, pp. 15-17, pp. 15-17, repr. fig. 1

- Molly Faries, "A Drawing of the Brazen Serpent by Michiel Coxie", Revue Belge d'Archeologie et d'Histoire de l'Art (1975), vol. 44, pp. 131-41, pp. 131-41, repr. p. 132, fig. 1

- "Principales Acquisitions des Musées en 1982", La Chronique des Arts, Gazette des Beaux-Arts (March 1983), 6th series, vol. 101, pp. 29-30, no. 164, p. 30, repr.

- Nicola Courtright, Northern Travelers to Sixteenth-Century Italy: Drawings from New England Collections, exh. cat., Trustees of Amherst College (Amherst, MA, 1990), cat. no. 2, pp. 2 and 14

- Karel G. Boon, The Netherlandish and German Drawings of the XVth and XVIth Centuries of the Frits Lugt Collection (Paris, France, 1992), vol. 1, under cat. no. 61, pp. 104 and 105 (n. 9)

- Nicole Dacos, “Michiel Coxcie et les romanistes: A propos de quelques inédits”, Handelingen van de Koninklijke Kring voor Oudheidkunde, Letteren en Kunst van Mechelen (Michiel Coxcie, Pictor regis (1499-1592). International colloquium, Mechelen, 5 en 6 juni 1992) (1993), vol. 92, no. 2, pp. 55-92, p. 78

- F. W. H. Hollstein, The New Hollstein : Dutch & Flemish etchings, engravings, and woodcuts, 1450-1700, Koninklijke van Poll, Rijksprentenkabinet, Rijksmuseum, and Sound + Vision Publishers (Roosendall, Rotterdam, and Ouderkerk aan den IJssel, 1993 - ongoing), Frans Floris (compiled by Edward H. Wouk, 2011), part I, p. xc (n. 176)

- Suzanne Folds McCullagh and Laura Giles, Italian Drawings before 1600 in The Art Institute of Chicago: A Catalogue of the Collection, The Art Institute of Chicago/Princeton University Press (Chicago, IL and Princeton, NJ, 1997), under cat. no. 335, p. 258

- Benoît Boëlens van Waesberghe, ed., European Master Drawings Unveiled, exh. cat., Ludion Amsterdam-Ghent (Amsterdam, 2002), under cat. no. 9, p. 30

- Edward Wouk, "Raffaello fiammingo: the graphic work of Frans Floris de Vriendt (1519/20-1570)" (2010), Harvard University, p. 223 (n. 85)

- Koenraad Jonckheere, ed., Michiel Coxcie 1499-1592 and the Giants of his Age, exh. cat., Turnhout (London, 2013), pp. 62, 63 (n. 36), 172, and 181 (n. 42)

- Stijn Alsteens, [Review] William W. Robinson, with Susan Anderson, "Drawings from the Age of Bruegel, Rubens, and Rembrandt: Highlights from the Collection of the Harvard Art Museums" (Winter 2015), p. 531

- William W. Robinson and Susan Anderson, Drawings from the Age of Bruegel, Rubens, and Rembrandt: Highlights from the Collection of the Harvard Art Museums, Harvard Art Museums (Cambridge, MA, 2016), cat. no. 20, pp. 85-87, repr. p. 86

Exhibition History

- Northern Renaissance Art: Selected Works, Busch-Reisinger Museum, Cambridge, 02/28/1984 - 04/08/1984

- Prints and Drawings from the Time of Holbein and Breugel, Busch-Reisinger Museum, Cambridge, 11/21/1985 - 01/12/1986

- Northern Travelers to 16th c. Italy: Drawings from New England Collections, Mead Art Museum, Amherst, 10/29/1990 - 12/09/1990

Subjects and Contexts

- Dutch, Flemish, & Netherlandish Drawings

Related Objects

Verification Level

This record has been reviewed by the curatorial staff but may be incomplete. Our records are frequently revised and enhanced. For more information please contact the Division of European and American Art at am_europeanamerican@harvard.edu