1999.182: Seven Insects

DrawingsIdentification and Creation

- Object Number

- 1999.182

- People

-

Pieter Withoos, Dutch (Amersfoort 1654/55 - 1692 Amsterdam)

- Title

- Seven Insects

- Classification

- Drawings

- Work Type

- drawing

- Date

- 17th century

- Culture

- Dutch

- Persistent Link

- https://hvrd.art/o/198740

Physical Descriptions

- Medium

- Opaque and transparent watercolor over graphite on cream antique laid paper, framing line in graphite

- Dimensions

- 21.3 x 31.8 cm (8 3/8 x 12 1/2 in.)

- Inscriptions and Marks

-

- Signed: Lower right, gray ink: P:W:fe:

- watermark: IHS (reversed S) with cross above and doublewired PD below; related to Heawood 2962 (London, 1670); for the initials PD, compare Churchill 6 (1654–79, initials of Pierre Dexmier?)

- collector's mark: verso, lower right, blue ink stamp: L. 3306 (Maida and George Abrams)

- inscription: verso, lower left, graphite: 2H / ... 17 [obscured by hinge]

Provenance

- Recorded Ownership History

- Mrs. L. Massey, sold; [Sotheby’s, London, 23 March 1971, lot 97]; through [Alfred Brod, London], to Maida and George Abrams, Boston (L. 3306, verso, lower right); The Maida and George Abrams Collection, 1999.182

Published Text

- Catalogue

- Drawings from the Age of Bruegel, Rubens, and Rembrandt: Highlights from the Collection of the Harvard Art Museums

- Authors

- William W. Robinson and Susan Anderson

- Publisher

- Harvard Art Museums (Cambridge, MA, 2016)

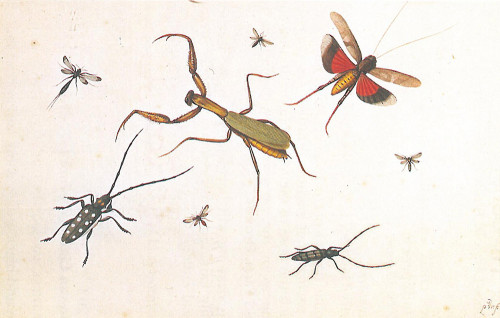

Catalogue entry no. 99 by Susan Anderson:

Pieter Withoos’s masterful watercolor Seven Insects combines entomological study with aesthetic sensibility: a large praying mantis (of the order Mantodea: family, Mantidae) anchors the composition, surrounded by, clockwise from the top, a leaf-footed bug (Hemiptera: Coreidae); a band-winged grasshopper (Orthoptera: Acrididae); a long-horned beetle (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae); an immature stink bug (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae); another long-horned beetle; and a bumble bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae).1 Even though the stark white background is reminiscent of mounted insect specimen collections or taxonomic print publications, the selection of unrelated families, even orders, of insects together in one drawing disregards scientific classification in favor of visual contrast of sizes, shapes, and colors. Common to Withoos’s approach to insect drawings, the seemingly haphazard placement of the specimens here evokes movement or flight rather than the staid appearance of neat columns and rows commonly found in scientific illustration.

Pieter Withoos established himself as a master of natural history watercolors with subjects including fruits, flowers, birds, and insects. He inherited this specialty from his father, Matthias (c. 1627–1703), whose training under Otto Marseus van Schrieck included joint travel to Italy and membership in the Schildersbent, a society of Dutch and Flemish painters in Rome. Like his master, Matthias depicted insects, reptiles, amphibians, and rodents among plants, all posed on the forest floor in a variety of dramatic tableaux. His output influenced not just Pieter, but also four of his siblings: Johannes (1648–1687/88), who specialized in landscape; Frans (1665–1705), who preferred insects and flowers in watercolor; and their sisters Alida (1659/60–1730), who focused on still-lifes and landscapes, and Maria (1663–1699/1710), who produced watercolors in general. In the wake of the French invasion of 1672, the entire family moved to Hoorn, where the younger generation must have come into contact with Johannes Bronckhorst (2013.171 ).2

Indeed, Pieter Withoos’s approach to insect drawing departs from the dramatic compositions of his father and other contemporaries in his sparer compositional style. In addition to landscapes prominently featuring animals—from Jan Brueghel II to Melchior d’Hondecoeter—the vanitas tradition persevered in Netherlandish art throughout the long seventeenth century, from Joris Hoefnagel to Herman Henstenburgh, with insects appearing among plants and other symbols of temporality, such as watches and skulls on ledges or in other settings. Insect specimens (and albums of drawings and prints of them) were often housed in cabinets by individuals entranced with the natural world, including by several people present in Amsterdam at the time of Withoos’s death there in 1692: these included Jonas Witsen, Frederik Ruysch, Levinus Vincent, and Nicolaes Witsen.3 Withoos and others in the coterie of artists who visited the naturalist Agneta Block at Vijverhof (e.g., Herman Saftleven; see 1999.169) practiced, albeit not exclusively, a branch of natural history drawing closely allied with the scientific tradition. This was especially true of Pieter Holsteyn I and II, Johannes Bronckhorst, and Herman Henstenburgh. This like-minded group pursued a fusion of aesthetics and science with similarly inventive compositions and exacting detail. They often added shadow beneath their insects to make the specimens appear as though resting on the paper, and frequently stressed their drawings’ scientific use by labeling them with letters, which would have corresponded to a separate, written identification key (Fig. 1).4 Withoos, in contrast, here leaves out any such labeling and, omitting shadows, allows the paper to be an ambiguous background.

Like Bronckhorst and his pictorial compositions of birds, Withoos appears to have used the same specimens, with variations, in more than one sheet. In another of his monogrammed watercolors of insects (one that last appeared in the New York trade; Fig. 2),5 Withoos depicted the praying mantis and band-winged grasshopper in the same compositional location, but repositioned the mantis’s legs into an attack-like stance and altered the grasshopper so that its antennae are pointed forward, its front four legs are missing, and its abdomen and rear legs are lighter in color. He likely also depicted the same longhorn beetle at the lower left in each sheet, although the differing spotted coloration on the New York drawing may indicate another specimen altogether.

Notes

1 James Carpenter, formerly Associate Professor of Biology and Associate Curator of Entomology, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, originally identified the insects by their common names in 1991; see William Robinson, Seventeenth‐Century Dutch Drawings: A Selection from the Maida and George Abrams Collection (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, Rijksprentenkabinet; Vienna: Albertina; New York: Pierpont Morgan Library; Cambridge: Harvard University Art Museums, 1991), cat. 101, p. 220. Brian Farrell, current Professor of Biology and Curator of Entomology, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, further provided the scientific identifications by order and family; email with the author, 28 April 2014. Given the vast field of entomology and the uncertain sources for Withoos’s specimens that would otherwise establish a geographic region from which these insects came, Farrell preferred not to hazard guesses as to genus and species.

2 Robinson, p. 220; Arnold Houbraken, De groote Schouburgh der Nederlantsche Konstschilders en Schilderessen, (first ed. 1718–21; reprint Amsterdam, 1943), vol. 2, pp. 146–48.

3 K. van Berkel in Ellinoor Bergvelt and Renée Kistemaker, De wereld binnen handbereik, Nederlandse kunsten rarieteiten verzamelingen, 1585–1735 (Zwolle, Netherlands, 1992), p. 182. See also Thea Vignau-Wilberg, Pieter Holsteijn the Younger, Haarlem 1614–1673 Amsterdam: Alderhande Kruypende en Vliegende Gedierten (Munich, 2013).

4 Pieter Holsteyn I, A Sheet with Six Insects (Fig. 1), 1660–62. Transparent and opaque watercolor, 160 × 207 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, RP-T-1899-A- 4262.

5 Pieter Withoos, A Sheet of Eight Insects (Fig. 2). Transparent and opaque watercolor, 232 × 340 mm. Sotheby’s, New York, 12 January 1994, lot 197, repr.

Figures

Acquisition and Rights

- Credit Line

- The Maida and George Abrams Collection, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts

- Accession Year

- 1999

- Object Number

- 1999.182

- Division

- European and American Art

- Contact

- am_europeanamerican@harvard.edu

- Permissions

-

The Harvard Art Museums encourage the use of images found on this website for personal, noncommercial use, including educational and scholarly purposes. To request a higher resolution file of this image, please submit an online request.

Publication History

- Franklin W. Robinson, Seventeenth Century Dutch Drawings from American Collections, exh. cat., International Exhibitions Foundation (Washington, D.C, 1977), cat. no. 85, pp. xiii, xvi and 91-92, repr.

- George Abrams, "Collectors and Collecting", Drawings Defined, ed. Walter Strauss, Abaris Books (New York, 1987), pp. 415-429, p. 422, repr. fig. 17

- William W. Robinson, Seventeenth-Century Dutch Drawings: A Selection from the Maida and George Abrams Collection, exh. cat., H. O. Zimman, Inc. (Lynn, MA, 1991), cat. no. 101, pp. 220-21, and p. 9, repr.

- George S. Keyes, "[Review] Seventeenth-Century Dutch Drawings. A Selection from the Maida and George Abrams Collection", Master Drawings (Winter 1992), vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 443-448, p. 446

- Master Drawings: 1530-1920 (January 24 to February 3, 2012), auct. cat., W. M. Brady & Co., Inc. (New York, 2012), under cat. no. 12, n.p., repr.

- Alvin L. Clark, Jr., Seventeenth-Century European Drawings in Midwestern Collections: The Age of Bernini, Rembrandt, and Poussin, ed. Shelley Perlove and George S. Keyes, University of Notre Dame Press (Notre Dame, 2015), under cat. no. 81, p. 198 (n. 233)

- William W. Robinson and Susan Anderson, Drawings from the Age of Bruegel, Rubens, and Rembrandt: Highlights from the Collection of the Harvard Art Museums, Harvard Art Museums (Cambridge, MA, 2016), cat. no. 99, pp. 324-326, repr. p. 325; watermark p. 383

- Robert Schindler, Bernd Ebert, and Anna Knaap, Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art, exh. cat., MFA Publications (Boston, 2024), p. 239

Exhibition History

- Seventeenth Century Dutch Drawings from American Collections, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 01/30/1977 - 03/13/1977; Denver Art Museum, Denver, 04/01/1977 - 05/15/1977; Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, 06/01/1977 - 07/15/1977

- Seventeenth-Century Dutch Drawings: A Selection from the Maida and George Abrams Collection, Rijksprentenkabinet, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 02/23/1991 - 04/18/1991; Albertina Gallery, Vienna, 05/16/1991 - 06/30/1991; The Morgan Library & Museum, New York, 01/22/1992 - 04/22/1992; Harvard University Art Museums, Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge, 10/10/1992 - 12/06/1992

- 32Q: 2300 Dutch & Flemish, Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, 03/09/2017 - 09/08/2017

- Rachel Ruysch: Nature into Art, Toledo Museum of Art, 04/13/2025 - 07/27/2025; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 08/23/2025 - 12/07/2025

Subjects and Contexts

- Collection Highlights

- Google Art Project

- Dutch, Flemish, & Netherlandish Drawings

Verification Level

This record has been reviewed by the curatorial staff but may be incomplete. Our records are frequently revised and enhanced. For more information please contact the Division of European and American Art at am_europeanamerican@harvard.edu