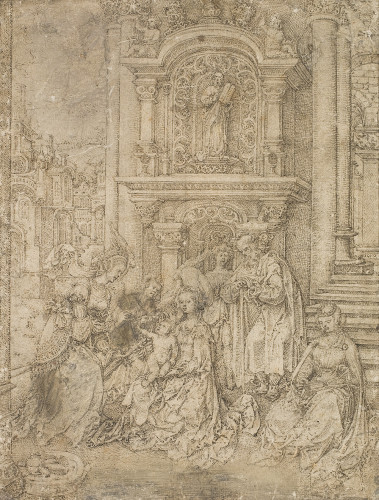

2004.85: Christ Disputing with the Doctors in the Temple

DrawingsIdentification and Creation

- Object Number

- 2004.85

- People

-

Circle of Jan Gossaert, Netherlandish (1473 - 1532)

- Title

- Christ Disputing with the Doctors in the Temple

- Classification

- Drawings

- Work Type

- drawing

- Date

- c. 1510

- Culture

- Netherlandish

- Persistent Link

- https://hvrd.art/o/171290

Physical Descriptions

- Medium

- Brown ink on parchment

- Dimensions

- 34.8 x 24 cm (13 11/16 x 9 7/16 in.)

- Inscriptions and Marks

-

- collector's mark: lower right, red ink, stamp: L. 77 (Antonio Barboza)

- collector's mark: lower left, black ink, stamp: L. 897 (Eugène Rodrigues)

- inscription: verso, upper center, graphite: 2.

- watermark: none

Provenance

- Recorded Ownership History

-

General Antoine-François Andréossy (according to Rodrigues sale catalogue). Antonio Barboza, Paris (L. 77, lower right). Eugène Rodrigues, Paris (L. 897, lower left), sold; [Muller, Amsterdam, 12-13 July 1921, lot 131, repr. pl. LII]; to Muller. Franz Koenigs, Haarlem; by descent to his heirs, sold; [Sotheby's, New York, 23 January 2001, lot 3, repr. p. 17], bought in and subsequently sold; to Vermeer Associates, Limited, Brampton, Ontario, sold; to Harvard University Art Museums; The Kate, Maurice R. and Melvin R. Seiden Special Purchase Fund in honor of Mary and Michael Gellert, inv. no. 2004.85.

NOTE: The sequence to Franz Koenigs directly from the auction at Muller's is not proven. The drawing may have bought in at that sale and then sold to Koenigs.

Published Text

- Catalogue

- Drawings from the Age of Bruegel, Rubens, and Rembrandt: Highlights from the Collection of the Harvard Art Museums

- Authors

- William W. Robinson and Susan Anderson

- Publisher

- Harvard Art Museums (Cambridge, MA, 2016)

Catalogue entry no. 43 by William W. Robinson:

When Jesus was twelve years old, Joseph and Mary took him to Jerusalem to observe the feast of the Passover. Unnoticed by his parents, Jesus remained behind when they departed on their homeward journey to Nazareth. Returning to Jerusalem, they searched for three days until “they found him in the temple, sitting in the midst of the doctors, both hearing them and asking them questions. And all that heard him were astonished by his understanding and answers” (Luke 2:41–50). The theme of Jesus’s disputation with the scholars in the temple occurs frequently in late medieval and Renaissance art, particularly in cycles devoted to the Life of the Virgin and the Seven Sorrows of the Virgin.1

Although the style and technique of Christ Disputing with the Doctors in the Temple relate it to works by Jan Gossart from the first decade of the sixteenth century, the drawing is not by Gossart but by a close follower. As Gregory Rubinstein and Stijn Alsteens have noted, the systematic parallel and cross-hatched strokes recall the refined pen work in The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine (c. 1503–8) in Copenhagen, Gossart’s earliest surviving work (Fig. 1).2 The putti that support the corbels at upper left and right resemble those in a capital in the right background of the Copenhagen drawing, and the putto at the top center of the Harvard sheet mimics those perched on the architectural frame above the statue of Moses in Gossart’s composition. The poses, gestures, and scale of the figures in the Harvard work are closer to a slightly later Gossart drawing, Emperor Augustus and the Tiburtine Sibyl in Berlin.3 Compared to the supple, varied strokes of the Berlin sheet, the lines in the Harvard work are more homogeneous, precise, and delicate, and the modeling of the figures and architecture lacks the breadth and fluidity imparted by Gossart’s robust handling of the pen.4

The unidentified draftsman of the Harvard composition imitated the eclectic, imaginatively combined decorative and architectural elements found in Gossart’s drawings, but modeled the temple interior on Albrecht Dürer’s Presentation of Christ in the Temple from the woodcut series Life of the Virgin (Fig. 2).5 The figure with the dangling sleeve and his arm around the column in the left foreground also derives from Dürer’s print, which was issued in proof impressions about 1505, before the series appeared in book form in 1511. The sheaves suspended from the ceiling and the round window in the rear wall are based on Dürer’s Christ Disputing with the Doctors in the Temple in the same series, where Jesus also appears as a diminutive figure deep within the temple space and astonished listeners occupy the immediate foreground.6

Harvard’s Christ Disputing with the Doctors in the Temple presumably dates from about 1505–10, roughly the same time as the drawings by Gossart to which it responds. Gossart joined the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke in 1503 and maintained his workshop in that city until he departed for Italy in October 1508. Guild records document that he registered two apprentices, Hennen Mertens in 1505 and Machiel in’t Swaenken in 1507. Hennen Mertens was almost certainly identical with Jan Mertens van Dornicke, the future father-in-law of artist Pieter Coecke van Aelst. According to some scholars, Jan Mertens van Dornicke produced the large oeuvre of paintings and several drawings attributed to the so-called Master of 1518. None of those drawings closely resemble Christ Disputing with the Doctors in the Temple, although the works attributed to the Master of 1518 probably date from at least a decade later than the Harvard sheet.7 Gossart’s output before 1508 contributed to the development of the style known as Antwerp mannerism, which was practiced by several workshops in the city during the second and third decades of the century.8 Like Gossart’s early drawings, the Harvard composition anticipates salient characteristics of Antwerp mannerism, including the fancifully arranged decorative elements, expressively posed figures, and elaborate costumes and headgear. Dan Ewing singled out the pronounced bilateral symmetry of the composition and the monumentality of the architectural forms—particularly the massiveness of the columns and plinths—as original, distinctive elements of the drawing within the context of Antwerp art of the period.9

Alsteens proposed that Gossart’s works in Berlin and Copenhagen—which, in addition to being meticulously executed virtuoso performances, are both signed by the artist—might be early examples of finished drawings made for collectors.10 Although not signed, Harvard’s Christ Disputing with the Doctors in the Temple is also a formal, flawlessly worked composition drawn on a large sheet of parchment, a more valuable support than paper. It could also have been an autonomous drawing intended for sale.

Notes

1 For example, Albrecht Dürer’s woodcut series Life of the Virgin includes the subject of Christ Disputing with the Doctors in the Temple (Rainer Schoch, Matthias Mende, and Anna Scherbaum, Albrecht Dürer: Das druckgraphische Werk, Munich, 2001–4, vol. 2, cats. 166–85, pp. 214–79 [the series]; cat. 181, pp. 265–67 [this subject]), as do altarpieces depicting the Seven Sorrows of the Virgin by Dürer (Fedja Anzelewsky, Albrecht Dürer: Das malerische Werk, Berlin, 1991, vol. 1, cats. 20–38v, pp. 132–39, repr. vol. 2, pls. 23–31), Bernard van Orley (Carol M. Schuler, “The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin: Popular Culture and Cultic Imagery in Pre-Reformation Europe,” Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, vol. 21, no. 1/2 (1992): 5–28, p. 6, fig. 1), Adriaen Isenbrant (Max J. Friedländer, The Antwerp mannerists: Adriaen Ysenbrant, Leyden and Brussels, 1974, vol. 11, no. 138, p. 82, repr. pls. 115 and 117) and the workshop of the Master of 1518 (Annick Born in Peter van den Brink et al., ExtravagAnt! A forgotten chapter of Antwerp painting 1500–1530, Antwerp: Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten; Maastricht: Bonnefantenmuseum Maastricht, 2005, cat. 82, pp. 193–95).

2 Gregory Rubinstein in the catalogue of the sale, Sotheby’s, New York, 23 January 2001, lot 3; Stijn Alsteens in conversation with the author (21 September 2011), and correspondence (25 September 2012). Jan Gossart, The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine (Fig. 1), brown ink, 227 × 172 mm. Signed, brown ink, HENNING OSAR. Copenhagen, Statens Museum for Kunst, KKSgb4828. Stijn Alsteens in Maryan W. Ainsworth, Stijn Alsteens, and Nadine M. Orenstein, Man, Myth and Sensual Pleasures: Jan Gossart’s Renaissance: The Complete Works (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; London: National Gallery, selected paintings only, 2010), cat. 69, pp. 318–20.

3 Jan Gossart, Emperor Augustus and the Tiburtine Sibyl, black ink, 339 × 278 mm. Signed, black ink, ANWER HENNI. Berlin, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, KdZ 15295. Stijn Alsteens in Ainsworth et al., cat. 91, pp. 362–64.

4 This is also the opinion of Rubinstein and Alsteens (see n. 2 above).

5 Albrecht Dürer, Life of the Virgin: Presentation of Christ in the Temple (Fig. 2), woodcut, 296 × 208 mm, British Museum, 1895,0122.633. Schoch et al., vol. 2, cat. 178, pp. 256–59.

6 Schoch et al., vol. 2, cat. 181, pp. 265–67.

7 Maryan Ainsworth in Ainsworth et al., pp. 9–10; Sytske Weidema and Anna Koopstra, Jan Gossart: The Documentary Evidence. Studies in Medieval and Early Renaissance Art History series, 65 (London and Turnhout, Netherlands, 2012), pp. 7–8. See Annick Born in Van den Brink et al., p. 225, for the biography of Jan Mertens van Dornicke. Born does not accept art historian Georges Marlier’s hypothesis that Van Dornicke can be identified with the Master of 1518. Maryan Ainsworth, on the other hand, tentatively accepts the identification of Van Dornicke (Hennen Mertens) with the Master of 1518; Maryan Ainsworth in Elizabeth Cleland with Maryan W. Ainsworth, Stijn Alsteens, and Nadine M. Orenstein, Grand Design: Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Renaissance Tapestry (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014) pp. 22–26, under cat. 1, p. 36, p. 350 (n. 6). For the drawings attributed to the Master of 1518, see Peter van den Brink in Van den Brink et al., cats. 53–57, pp. 136–43. My thanks to Dan Ewing and Stephanie Schrader for references to Gossart’s pupils.

8 Maryan Ainsworth and Stijn Alsteens in Ainsworth et al., pp. 11 and 89–90, and under cat. 83, p. 345; Annick Born, Ellen Konowitz, Lars Hendrikman, and Peter van den Brink in Van den Brink et al., p. 12 and cats. 10–16, pp. 41–53.

9 Dan Ewing, professor of art history, Department of Fine Arts, Barry University, Miami, Florida (email to the author, 12 May 2014).

10 Stijn Alsteens in Ainsworth et al., p. 89.

Figures

Acquisition and Rights

- Credit Line

- Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, The Kate, Maurice R. and Melvin R. Seiden Special Purchase Fund in honor of Mary and Michael Gellert

- Accession Year

- 2004

- Object Number

- 2004.85

- Division

- European and American Art

- Contact

- am_europeanamerican@harvard.edu

- Permissions

-

The Harvard Art Museums encourage the use of images found on this website for personal, noncommercial use, including educational and scholarly purposes. To request a higher resolution file of this image, please submit an online request.

Publication History

- Stijn Alsteens, [Review] William W. Robinson, with Susan Anderson, "Drawings from the Age of Bruegel, Rubens, and Rembrandt: Highlights from the Collection of the Harvard Art Museums" (Winter 2015), p. 531

- William W. Robinson and Susan Anderson, Drawings from the Age of Bruegel, Rubens, and Rembrandt: Highlights from the Collection of the Harvard Art Museums, Harvard Art Museums (Cambridge, MA, 2016), p. 18; cat. no. 43, pp. 154-157, repr. p. 155

Subjects and Contexts

- Dutch, Flemish, & Netherlandish Drawings

Verification Level

This record has been reviewed by the curatorial staff but may be incomplete. Our records are frequently revised and enhanced. For more information please contact the Division of European and American Art at am_europeanamerican@harvard.edu