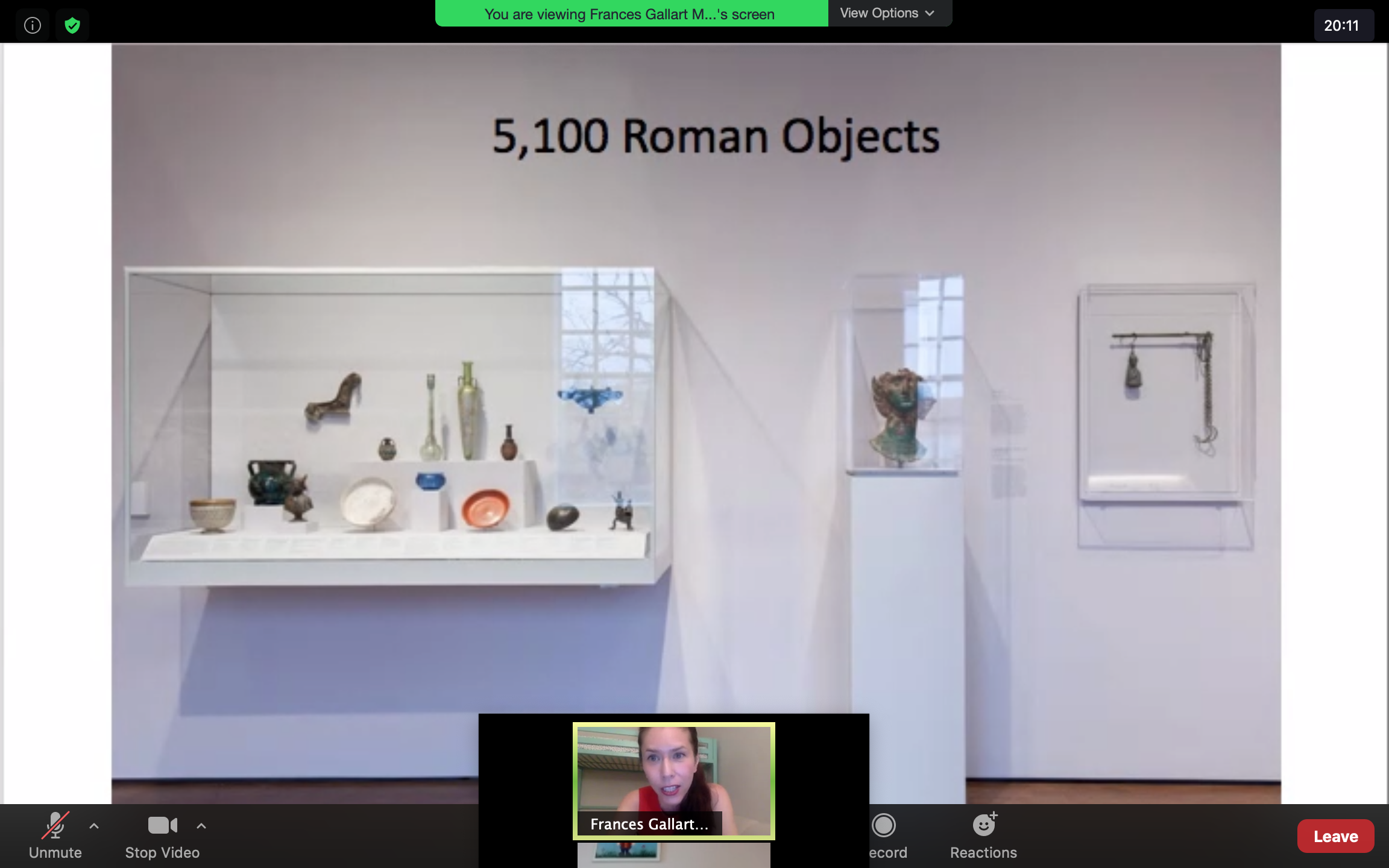

It was March 12, 2020. Curatorial fellow Frances Gallart Marqués had just been talking with visitors when it was announced that the museums would temporarily close to the public as a pandemic precaution.

She and other fellows had been leading a tour about “dangerous women,” organized by Jen Thum, who was then a fellow in the Division of Academic and Public Programs, to celebrate International Women’s Day. The second part of the tour, scheduled for the next day, would never happen. In those first moments of uncertainty, we fellows felt deeply sad to imagine that we would no longer be able to interact with the public. But we would soon realize that the pandemic, in removing the physical museum from the equation, would help us realize more equitable ways of interacting with the people we serve.

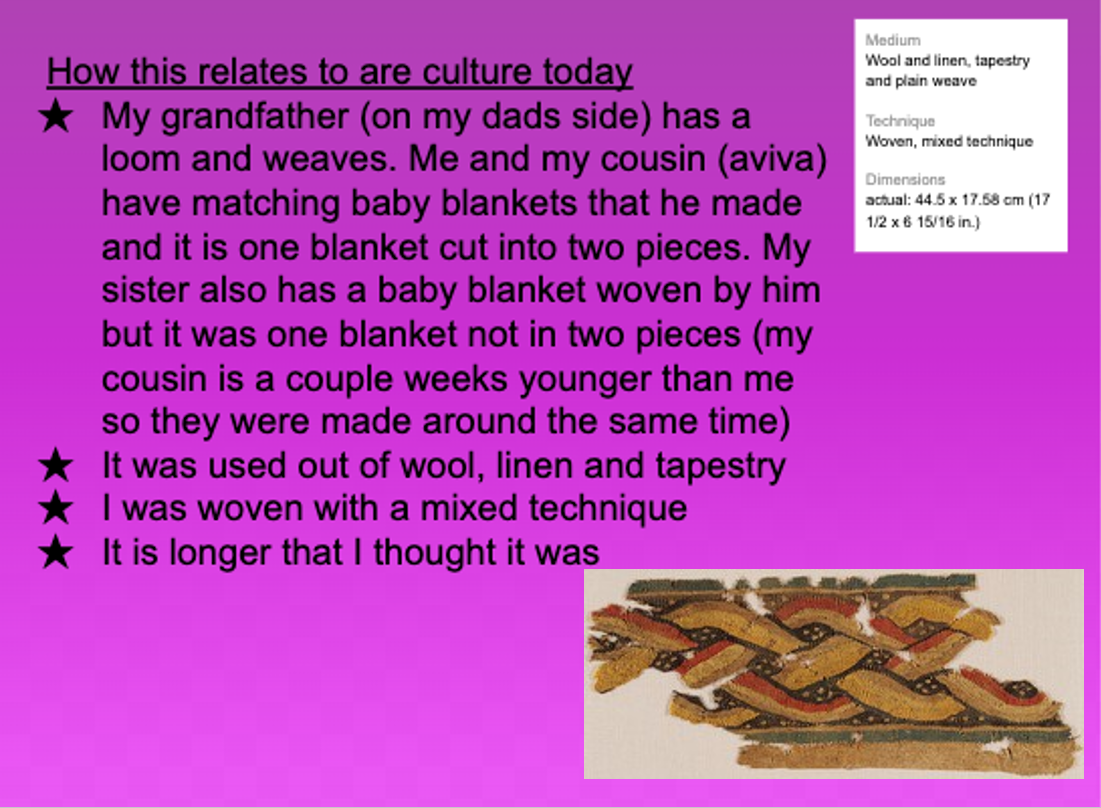

Jen and Frances, who at the time was a fellow in the Division of Asian and Mediterranean Art, are both archaeologists. In their teaching and public programs, they encourage people to make connections between their lived experiences and the things they want to learn about. Minoritized people are often asked to leave their personal experiences—and the knowledge that comes with them—at the door when entering elite spaces such as art museums, and ancient art in particular has been used to justify racial and social inequality. This gives such connections a heightened urgency. Because the Harvard Art Museums strive to be a welcoming place to communities on campus and beyond, it is imperative that staff foster visitors’ learning and appreciation on their own terms and validate multiple perspectives. We kept this top of mind when we thought through how we might engage with K-12 audiences in the museums’ online space.

Frances and Jen were joined by Yan Yang, the curatorial assistant for the collection in the Division of Asian and Mediterranean Art, in their efforts to increase accessibility to the museums’ collections while also giving a sense of agency to our younger visitors. Because the online space means we don’t have to worry about the restrictions on programming imposed by in-person learning, such as group size in the galleries or school bus parking, we were able to make new school partnerships. Remote teaching also gave us room to experiment with new and different teaching approaches. In this article, we share three examples of how we shifted the focus of our engagements with kids in this era of remote learning.