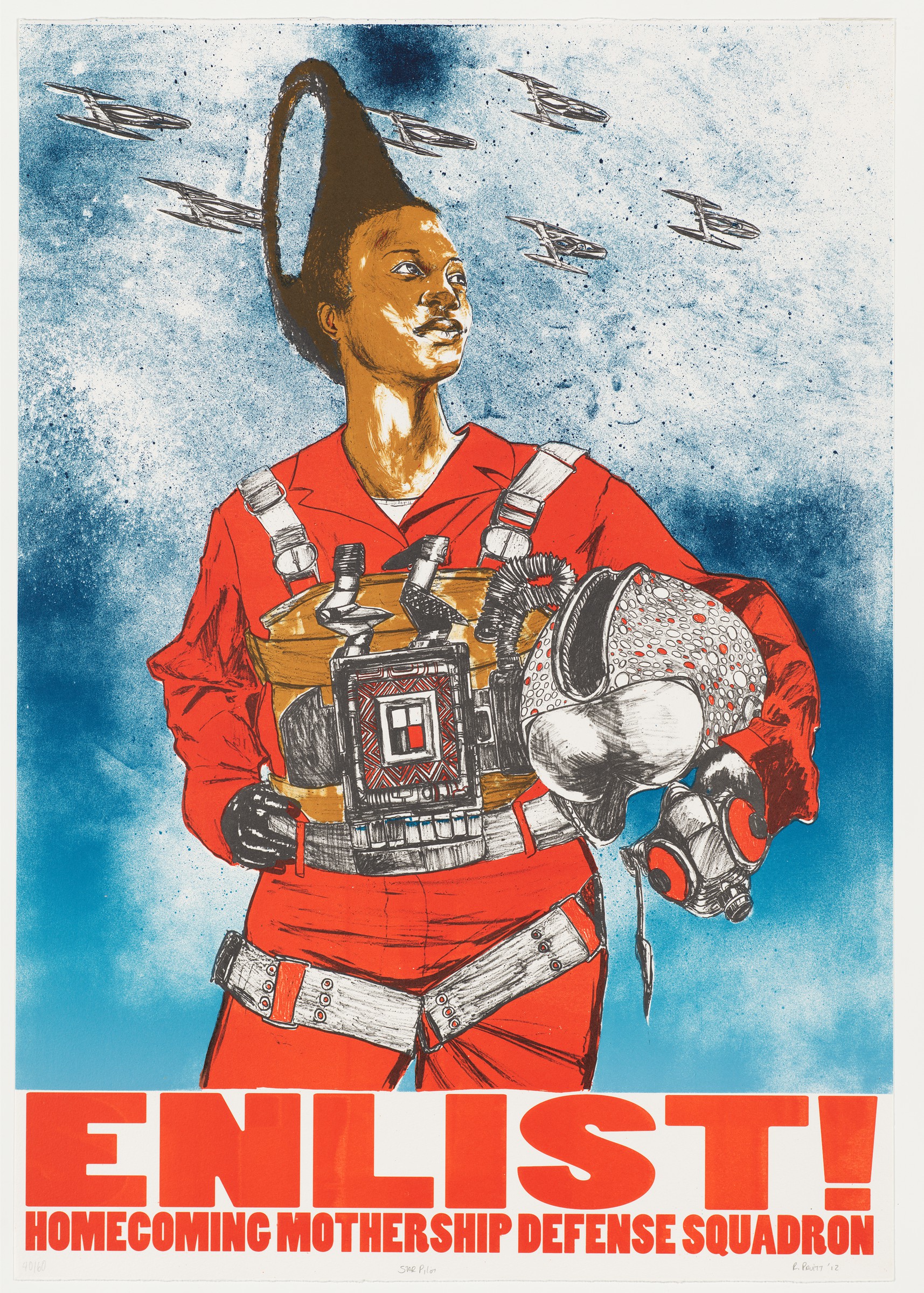

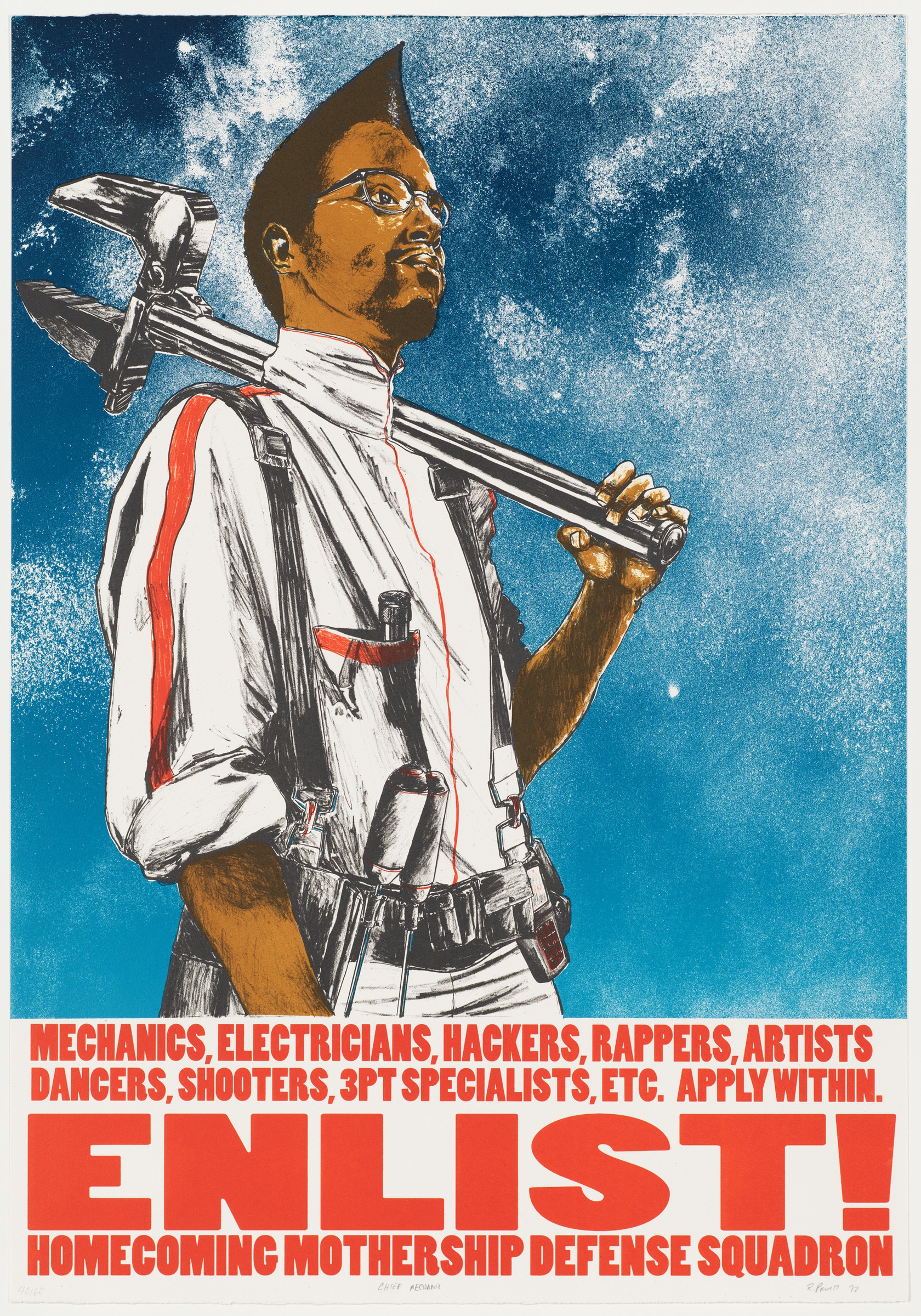

Two eye-catching prints by contemporary artist Robert Pruitt—Star Pilot and Chief Mechanic—are currently on view in the Harvard Art Museums exhibition Prints from the Brandywine Workshop and Archives: Creative Communities.

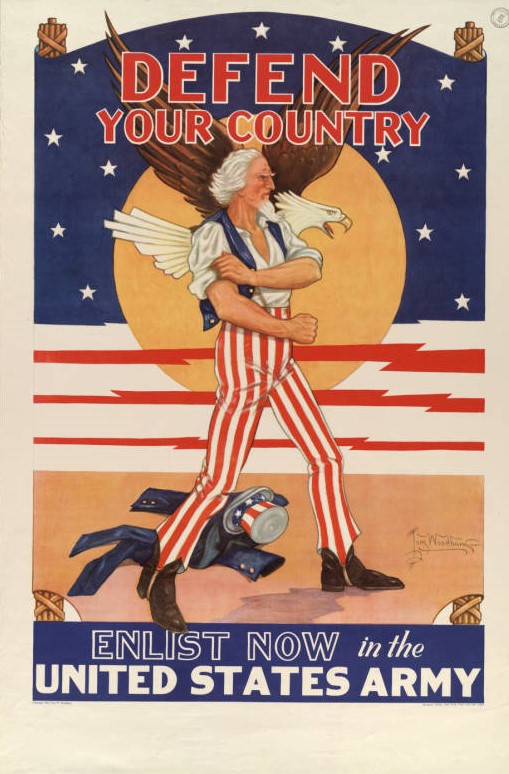

Bold red text at the bottom of both works exhorts viewers to enlist. Above this directive, a lone figure occupies each composition’s foreground, head tilted slightly upward, gaze fixed on something beyond the picture plane. The figures’ dress, their hairstyles, and the objects they hold, combined with the prints’ additional text—“Homecoming Mothership Defense Squadron”—align these works with imagery and themes associated with Afrofuturism. Often characterized as a transdisciplinary movement or creative mode, Afrofuturism has been embraced by artists, musicians, activists, and intellectuals to envision a world in which African-descended peoples forge culturally and technologically advanced societies.

Pruitt created these lithographs during a 2012 residency at the Brandywine Workshop and Archives, a Philadelphia-based nonprofit organization that offers arts programming and sponsors printmaking residencies for practicing artists. Over the course of his career, Pruitt has produced varied artworks across media, including video, sculpture, and comic books. His chief output, however, has been large-scale, multimedia figural drawings on paper. Many of his recent works, such as Geledé Garveyite(2020), are on paper that is hand-dyed, often with coffee. Atop these supports, he combines charcoal, pastel, and conté, which is a crayon made from powdered graphite or charcoal mixed with clay. Blending elements drawn from hip-hop culture, science fiction, and comic books, Pruitt executes sensitive and incisive portraits of friends, family, and community members. His subjects often occupy most of the page and appear before an evacuated background. In this way, Pruitt offers open-ended narratives about his sitters—they could be anywhere in any era, simultaneously inhabiting past, present, and future.